A CoB-assisted adventure in lamprey embryology

Posted by Tetsuto, on 20 January 2017

This is the latest dispatch  from a recipient of a Company of Biologists Travelling Fellowship.

from a recipient of a Company of Biologists Travelling Fellowship.

Learn more about the scheme, including how to apply, here, and read more stories from the Fellows here.

Tetsuto Miyashita

Pasadena.

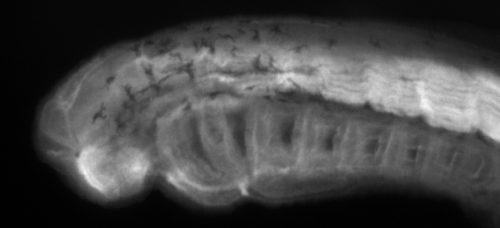

Everyone gets different images for the place. JPL. Richard Feynman. The Big Bang Theory. I can’t dissociate the image of Pasadena from lampreys. Lampreys? That blood-sucking, eel-like, slimy fish?

The Company of Biologists Travelling Fellowship allowed me to work on lamprey embryology in Marianne Bronner’s lab at Caltech in summer 2016. The experience was fantastic, although my colleagues in the lab might have felt at times as if I was the blood-sucking lamprey — following them around, asking a million questions, and trying to absorb all I could.

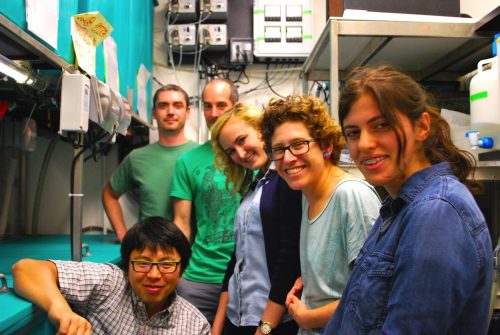

There already is an excellent post about lamprey lab in the Day in the Life in the Lab series by Daniel Meulemans Medeiro’s lab. So I am not going to repeat it here. Also, there is an excellent resource in David McCauley’s website that you should check out. In this post, I will focus on Team Lamprey in the Bronner lab and report about the fabulous people behind the neural crest research in lampreys. Take a look at our group photo.

Stephen Green is the hub of the Team Lamprey. Readers of the Node may recognize his name from the paper on mesodermal development in hemichordates that comes from his PhD dissertation work with Chris Lowe (Stanford University). Now at the Bronner lab, his meticulous and precise work that is showcased in the hemichordate paper has been teasing apart the developmental intricacy of neural and skeletal derivatives of neural crest in lampreys. While running his own research, Stephen is the master of the lamprey facility. He takes such a care of the animals that he was even witnessed walking in the lab past midnight, just to check that everything is running properly for the holding tanks that were set up earlier in the week. Take it as the sign of dedication, diligence, or even something else as you may, he does it matter-of-factly. Team Lamprey owes to him all these years of smooth operation, without which all of our work is unthinkable.

Hugo Parker, a postdoc with Robb Krumlauf at Stowers Medical Institute, is a long-time visitor to the lab. You can read his featured work on the Hox regulation in lamprey hindbrain development here in Nature or here in Bioessays. Hugo pioneered a reporter expression assay for this work when he was a PhD student with Greg Elgar, and he has been using it to study the evolution of regulatory mechanisms in hindbrain rhombomeres. His reporter assay gave lamprey researchers a tool to test functional evolution at the level of enhancers — adding a layer of comparison above gene expression profiles. Aside from serious research, Hugo hosts lab parties in the form of croquet competition in the campus front yard. Despite his competitive edge, and despite his love of this rather mundane sport, he has yet to win the prize, Lamprey Cup.

Splitting her time between Oxford and Cape Town, Dorit Hockman travels halfway around the world to work in the Bronner lab. She began her career with limb development in bats (see this paper in PNAS), went through the MBL Embryology course, trained under Clare Baker at the University of Cambridge, and finally arrived at lampreys for her postdoctoral work. Dorit brings computational skills and extensive training in the cutting-edge methods to study non-coding elements (like ATAC-seq). She works on a variety of projects around lamprey development, and one of the early fruits is the fate map of cranial sensory ganglia. Dorit actually joined me on one of my field projects to collect early jawless vertebrate fossils in South Africa. In the photo, she is standing at the locality that produced the world’s oldest fossil lamprey, Priscomyzon.

After completing her PhD with the famed sea urchin GRN guru Dave McClay, Megan Martik has just made a transition to the vertebrate world (see here for her PhD work). She handles two models — zebrafish and lampreys. This summer was her first lamprey spawning season. Megan was practicing with CRISPR/Cas9 and apprenticing in running the lamprey facility. Her research interest ultimately addresses the age-old question: how developmental repertoires differentially evolved between cephalic and trunk neural crest cells. Her recent adventure in China gave her an opportunity to speak with the evolutionary morphologist Shigeru Kuratani, whose lab has been leading the study of lamprey development over the last two decades. A photograph from the conference captures them engaged in what must have been a very lively discussion!

Aya Jishi, an undergrad at Caltech, is already a seasoned lamprey embryologist. She has volunteered with the lamprey for four years. She began with maintaining embryonic cultures and as an undergrad is now examining lamprey neurogenesis and is often seen working away at a microtome. Although hegraduated with a PhD before this last spawning season, Benji Uy also started in the Bronner lab as a high school student and continued his way through undergrad and PhD working on Sox family in lampreys. These prodigies are making their headways into a promised career in medicine, and the lamprey community will miss their talents

Finally, a bit about myself… I am a paleontologist. More precisely, I belong to a growing population of paleontologists to address evolutionary questions with both fossils and embryos. To me, the interest came naturally when I was a high school student. I worked as an assistant for Philip Currie, a Canadian dinosaur paleontologist who had a long-standing interest in the growth of theropod dinosaurs. His favourite anatomical reference at the time was Edwin Goodrich’s Studies on the Structure and Development of Vertebrates. When I had nothing to do on a cold wintery day in the museum, I would pull out Julian Huxley’s On the Problems of Relative Growth or Stephen J. Gould’s Ontogeny and Phylogeny from his bookshelf and flip through — although the prose of the latter was practically impenetrable for a Japanese high school student.

This early education had a profound influence as I developed my research interest beyond dinosaurs, and the Embryology course at the Marine Biological Laboratory reinforced it. I am not the only paleontologist who tried to learn the tricks of developmental biology. My colleagues like Katharine Criswell (the University of Cambridge) and Aidan Couzens (Flinders University) went through the program too. Recently I found in the biographical record that even Alfred Romer, a revered vertebrate paleontologist of the mid-20th century, spent his formative summers (1919-1921) at MBL to study embryology while he was a graduate student (that’s also where he met his future wife, Ruth Hibbard). This explains Romer’s in-depth understanding of development so eloquently displayed in the textbooks and papers he wrote. I feel a bit of connection here — Romer advised Robert Carroll, who advised my advisor.

My intellectual meanderings over the last few years led me to lamprey embryology at the Bronner lab. While on the COB Fellowship, I learned CRISPR/Cas9, cloned several genes potentially expressed in the skeletal tissues in the late stage of development, ran multiple rounds of in situ, and basically took an advantage of the environment to interact with the members of the Team Lamprey. As you can see, we all bring in different skill sets and interests that feed into a catalytic reaction over a summer of working together. Certainly, it is no easy work. In the height of the spawning season, you come in to run experiments in the morning, inject in the afternoon, and sort, spread, and collect embryos in the evening. Sometimes most embryos in the batch die. Sometimes you repeat PCRs for weeks just to get a single gene cloned. But even in those hard times when one feels somehow inadequate, it is worth the effort because science is as much about people you work with as about the animals you work on. My gratitude to the COB for awarding a Travelling Fellowship comes down to this point. I brought back from Pasadena more than just data. It gave me an opportunity to interact with this fabulous Team Lamprey and call each one of them my friend. Finally, I thank Marianne Bronner and her lab members for hosting me in such a welcoming community. Check out their work at the lab website here.

(12 votes)

(12 votes)