Setting the record straight- an interview with Daniel St Johnston

Posted by the Node, on 3 December 2013

Professor Daniel St Johnston is a prominent developmental biologist and the current director of the Gurdon Institute in Cambridge (UK). The St Johnston lab recently retracted two papers, in what Retraction Watch lauded as a poster case of ‘doing the right thing’. The Node interviewed Daniel and discussed the case, and how his experience highlighted the shortcomings of the current system of ‘setting the record straight’.

Tell us a little bit about the background of this case

We had published two papers, one in The Journal of Cell Biology and another in Developmental Cell, on a low energy polarity pathway. In each case the basic observation was that mutant follicle cells, marked by the loss of GFP, showed a loss of polarity under starvation conditions. Specifically they lost apical aPKC and lateral Discs large. When we tried to follow up this research we could see the phenotype, but it was frustrating because sometimes it was there and sometimes it wasn’t. We initially assumed that we weren’t starving our flies properly. We tried all sorts of drugs that mimic starvation but were not able to change the frequency at which we could see the phenotype. Two members of my lab, Dan and Timm, started to suspect that there was something wrong technically, and came up with this idea that the GFP negative cells weren’t actually real clones but damaged cells. Between our two papers coming out and realizing what was going on, Lynn Cooley’s lab showed that follicle cells remain attached to their sisters after mitosis, generating clones of cells that are connected by small cytoplasmic bridges. This meant that if you just nicked one cell, GFP – and polarity markers – could leak out from a whole cluster of cells, looking exactly like a mitotic clone. The killer experiment was marking the clones in a different way: if you positively mark them with GFP and repeat the experiment, you can observe some GFP-marked clones where you never see the polarity phenotype, and GFP-negative clones where you do. The final bit of the explanation was to clarify why the phenotype seemed to be starvation-dependent. If you starve flies, their ovaries are much smaller, it’s harder to dissect them apart and so you cause damage more frequently. Once we discovered this artefact it basically invalidated the main conclusion of both papers. We felt obliged to set the record straight.

We had published two papers, one in The Journal of Cell Biology and another in Developmental Cell, on a low energy polarity pathway. In each case the basic observation was that mutant follicle cells, marked by the loss of GFP, showed a loss of polarity under starvation conditions. Specifically they lost apical aPKC and lateral Discs large. When we tried to follow up this research we could see the phenotype, but it was frustrating because sometimes it was there and sometimes it wasn’t. We initially assumed that we weren’t starving our flies properly. We tried all sorts of drugs that mimic starvation but were not able to change the frequency at which we could see the phenotype. Two members of my lab, Dan and Timm, started to suspect that there was something wrong technically, and came up with this idea that the GFP negative cells weren’t actually real clones but damaged cells. Between our two papers coming out and realizing what was going on, Lynn Cooley’s lab showed that follicle cells remain attached to their sisters after mitosis, generating clones of cells that are connected by small cytoplasmic bridges. This meant that if you just nicked one cell, GFP – and polarity markers – could leak out from a whole cluster of cells, looking exactly like a mitotic clone. The killer experiment was marking the clones in a different way: if you positively mark them with GFP and repeat the experiment, you can observe some GFP-marked clones where you never see the polarity phenotype, and GFP-negative clones where you do. The final bit of the explanation was to clarify why the phenotype seemed to be starvation-dependent. If you starve flies, their ovaries are much smaller, it’s harder to dissect them apart and so you cause damage more frequently. Once we discovered this artefact it basically invalidated the main conclusion of both papers. We felt obliged to set the record straight.

Why did you think that a retraction was necessary? Was there an alternative way to correct the papers?

We wrote a paper (now out in Biology Open) explaining this artefact, which I forwarded to the editors of both JCB and Developmental Cell. I told them that it was important that this work was linked to the original papers, because it showed that many of the results are due to an artefact. They both came back with the same message – that this looked like a case for a retraction.

We had collaborated in both papers with labs that provided the key mutants. In the JCB paper, Jay Brenman had done a very large screen that isolated the first AMPK mutants in Drosophila on the basis of a neural phenotype. That data was in the original paper and is all still true. Actually that paper was probably more highly cited for the identification of those alleles than for the spurious low energy polarity pathway! Jay wasn’t very happy to have to retract what was a major piece of work from his lab that was still true and still being cited.

Was there a way to republish this data?

We asked JCB whether we could retract only part of the paper, but we were told that this was not possible- a retraction is a retraction. Furthermore once a paper is retracted no one can cite it because it ceases to exist after a while. That held things up for quite a long time because we were stuck at an impasse. At this point I called up Jordan [Raff, Editor-in-chief of Biology Open] and asked him whether he thought Biology Open would be prepared to republish this part of the work, as it is important data and will be cited in the future. Jordan immediately said yes.

The next step was to make sure that everything happened simultaneously, because otherwise this data would be published twice, which would also have been a major offence. The three journals, Developmental Cell, JCB and Biology Open, agreed on a date to publish our paper explaining the artefact, Jay’s paper republishing his original mutants, and the two retraction notices.

You mention your concerns regarding your collaborator. Were you worried about the impact in your lab members and your own career?

I am worried about the career of the first author, who was a member of my lab. But what can you do? – the data aren’t true! As for the impact in my career, time will tell. In an ideal world it will be fine, as long as people look carefully enough to realise that we willingly retracted the papers. The alternative strategy would have been to just publish a paper saying that those results were wrong and hope that people would make the link. No one would have noticed, and it would have probably been better for the careers of everyone involved. But it would have meant that people, especially those in more distant research fields, might carry on citing these papers that aren’t correct.

It is actually worse to discover your own mistakes than other people’s. As scientists, we publish plenty of papers contradicting the results of previous papers from a different lab. That is how science works and it’s normal. But if you do it to yourself then you are in much worse state, career-wise.

Did you get positive feedback from the community?

I gather that it was discussed on Twitter with generally positive responses. I did talk to the author of one of the papers that erroneously attributed a polarity phenotype to a mutant because of this artefact. I asked him if he minded that we included in our Biology Open paper a repeat of his experiment, showing that you didn’t get that phenotype when you made sure that the artefact wasn’t occurring. He was great about it- he agreed that it needed to be corrected and was happy that I mentioned that his result is wrong. I think we have done the best we possibly could in terms of correcting the scientific record.

Do you think this experience highlighted problems with the current process of getting the record straight?

The main concern is that the majority of retractions take place because someone has done something deliberately wrong: manipulating figures or something worse. Those retractions are the ones that attract all the attention and people’s careers deservedly suffer as a result. Once you realise someone is faking their data, you cannot really trust anything else that they do. I view being a lab head almost as being a trademark- you have to protect the integrity of what you produce. Our case is almost the opposite of a retraction due to data manipulation. We withdrew the paper because we made an honest mistake and we wanted to clear up the record – so people know that when we make a mistake we admit it and we sort it out. The fact that these two different kinds of retractions are indistinguishable when you look at the citation does make things more complicated. Without reading the retraction notices in detail, or going to Retraction Watch, you just think: ‘oh, so and so has retracted two papers, they must be dodgy in some way’. It would be useful to have some way to distinguish between these two types of retraction.

My feeling is that the current set-up discourages people from acknowledging their mistakes. The incentives are not right for trying to get the most accurate description of what is known and what is known to be wrong in the public domain. And what we are talking about here is just the tip of the iceberg. There is much more stuff in the literature that is wrong and never gets corrected. If everyone was honest about it, and retracted papers that they found to be seriously wrong, there would be many more retractions and much less stigma.

The other problem is that, as far as I can understand, you can correct things if you get them slightly wrong but if you get things majorly wrong then you have to retract the whole paper, even if some of the data are perfectly sound. It seems wrong that reagents that are extremely useful can disappear from the literature at a blink of an eye.

– Retraction notice: LKB1 and AMPK maintain epithelial cell polarity under energetic stress, Journal of Cell Biology, vol 177 nr 3, 2007

– Retraction notice: Dystroglycan and Perlecan provide a basal cue required for epithelial polarity during energetic stress, Developmental Cell, vol 16, 2009

– St Johnston lab Biology Open paper describing the artefact: Damage to the Drosophila follicle cell epithelium produces “false clones” with apparent polarity phenotypes, Biology Open, ePress

– Brenman lab Biology Open paper republishing mutant screen: Isolation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) alleles required for neuronal maintenance in Drosophila melanogaster, Biology Open, ePress

– Retraction Watch article on this case: Data artifact claims two fruit fly papers from leading UK group- who offer model response

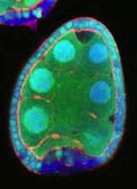

Image from the St Johnston lab’s Biology Open paper showing damage-induced false clones

(15 votes)

(15 votes)

Excellent and informative interview! Its unfortunate that careers may be damaged; if anything, such action demonstrates scientific integrity and should serve as an asset. Professor Johnston’s point about distinguishing between honest and dishonest retractions strikes me as a key point, but how could we make the difference readily clear? Perhaps a simple annotation affixed to the “retraction” citation would help?