Burning down the house I- bad ideas

Posted by Journal of Cell Science, on 6 November 2015

This Sticky Wicket article first featured in Journal of Cell Science. Read other articles and cartoons of Mole & Friends here.

“Watch out, you might get what you’re after! Dee-dee dee-dee-dee-dee. I’m an or-din-ar-y guy.” Hey, there. Just chilling to some old tunes and enjoying a cloudy day, curled up with some journals and a cup of ‘tea.’ “There. Has. Got. To. Be. A. Way.”

Speaking of reading, have you ever noticed that there are some ideas, although discredited (at least inmy mind), that will just not go away? In my own fields (there are a few fields I work in) there are a lot of examples of these. I’m sure you can identify some too. Examples? ‘Nature is logical.’ ‘Evolution seeks the simplest solution to a problem.’ ‘Biological processes are elegant (in the formal sense).’ ‘We evolved from organisms that are alive today.’ ‘There is a ladder of evolutionary progress.’ And then there are many that go in the form, ‘Things work like this: X causes Y.’ Or even worse, ‘X explains Y.’ Many of these are specific to an area of course, but you know what I mean. I hope you know what I mean.

Someone publishes something shaky, or explained as an artifact, and it gets cited and cited and cited. Why? I bet there are a bunch of reasons, and before we wax on about how we might do something about this, it might be good to consider the reasons. Maybe we don’t want to do something about it. Or maybe we do. I’m in a ‘list’ sort of mood, so here is a list. Reasons why questionable (or outright wrong) stuff sticks around. Or, if you prefer: how bad ideas survive.

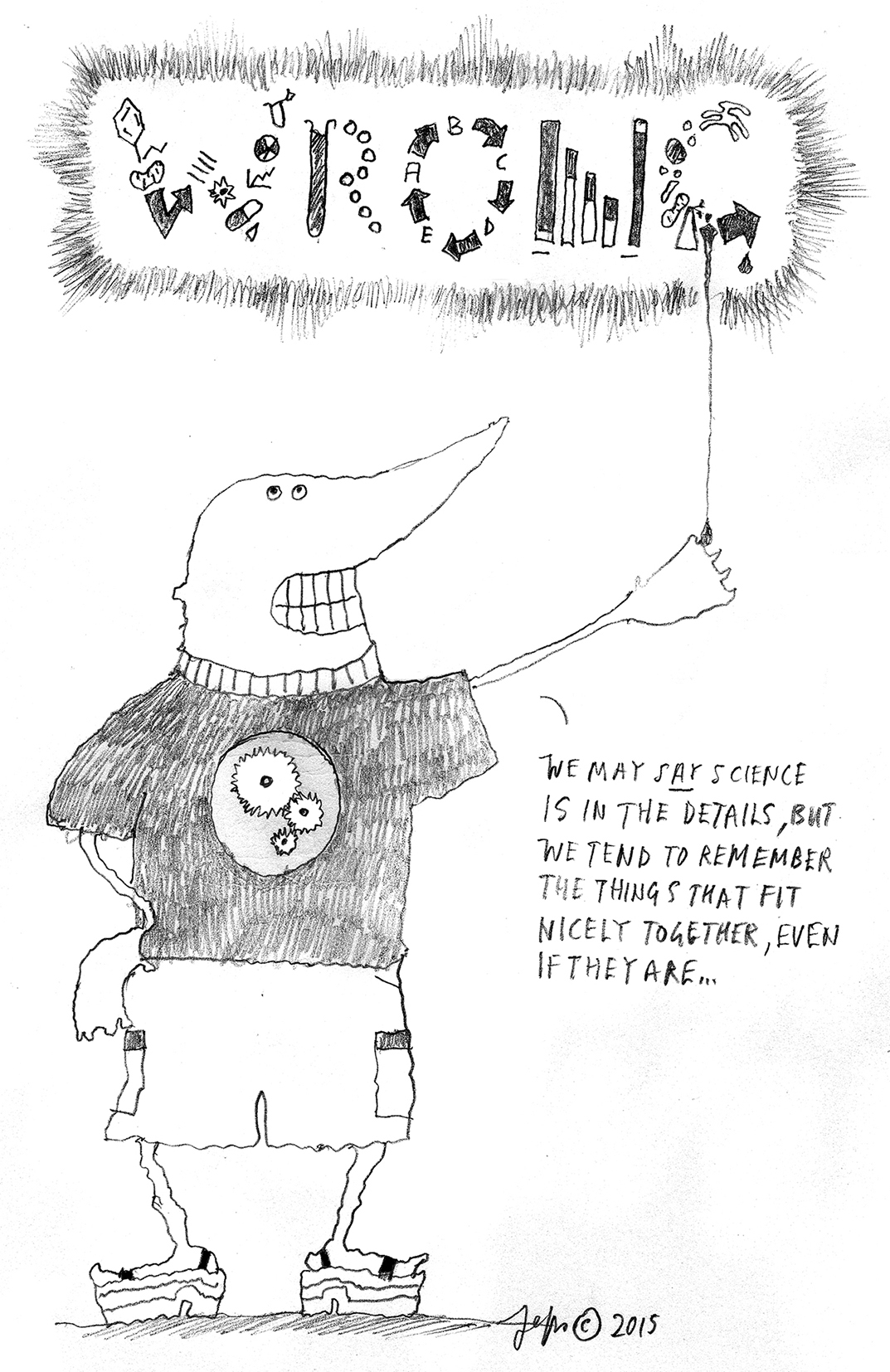

1. The idea is attractive on the surface. This is one reason why some ideas just won’t curl up and go away. As humans, we want explanations that we can wrap into neat little packages. If we have only a superficial understanding of a process, or sadly, even if we have a very good understanding, we may jump to untested conclusions and assume that they are correct. And if someone informs us that they are not, we can forget this information in favor of the ‘neat package.’ We may say that science is in the details, but we tend to remember the things that fit nicely together, even if they are wrong. Some philosophers of science insist that our mission is to disprove hypotheses, but while this sometimes is indeed the case, most of us have an idea and find evidence to support it. The more we like an idea, the more readily we enlist ‘facts’ into its support, and discount those that don’t fit. Of course we should resist this temptation, but as I say, it’s human nature.

2. The people who promote the idea don’t go away. This is something I realized a long time ago: when I was a feisty young Mole, I might hear a talk, or read a paper, that I dismissed as nonsense (okay, I still do that). But then I’d make the mistake of thinking that that was the end of it. Since then I’ve noticed that when a popular idea is disproven, the folks who have invested time and effort in the idea can continue to promote it, choosing to ignore the inconsistencies. Small groups continue to have meetings where they all agree to the discredited idea, and they publish (perhaps by having each other review the work). The ‘impact’ is often minimal, but it doesn’t go away. One field I work in has a lot of such ‘splinter groups’ and if a member of such a group happens to be chairing a more major meeting (it happens!) we find whole sessions devoted to ideas that we thought had died years ago. And sometimes, if a proponent of a discredited idea has influence (by position, or perhaps by other, more valid contributions) some of us in the mainstream prefer to cite the ideas rather than ‘rocking the boat.’ It’s easier.

3. We’re lazy. There, I’ve said it. We really are. And by this, I mean, intellectually lazy. We are passionate about the work we are doing, and want people to take it seriously, but when we put it into the context of the literature we often rely on information we have gotten from reviews rather than educating ourselves with a critical reading of the primary literature. And here’s where this gets really bad: when we write a review, we rely on earlier reviews for our information. “But Mole,” you counter, “when I write a review I do literature searches, I don’t rely only on older reviews!” Good for you. But how often to you only depend on what the abstract of a paper says when you need a few bits of information to make a point? How often do you examine the data in support of a statement you wish to make in your review article, or the introduction of your paper? I don’t mean you, of course, I mean ‘other people.’ Lazy people.

4. Even wrong ideas are useful. This is insidious, and it happens all the time. Say we have submitted a body of work that we feel makes an important contribution, but our reviewers want to know ‘the mechanism’ responsible for one of the observations. Finding the actual mechanism could take us years, and it isn’t really the point of the paper. But there is an idea out there, however discredited, that we can invoke to satisfy the reviewer. So we identify the correlates predicted by the idea, show them in our system, cite the questionable literature, and hope we can slide it past the reviewer (who is busy working on his or her own work, so lets it go). Presto, another bad idea gets a new life.

5. Even bad ideas are based on stuff that works. Not always, but sometimes. I’ll give you an example. Years ago, when the world (and siRNA) was young, there was a construct that apparently silenced an interesting gene and gave a useful phenotype. It turned out that it was off target, and the authors made sure to let the readership know (and kudos to them for their prompt transparency). But that didn’t stop dozens of papers that used the same construct to produce the phenotype in their own systems, publishing that it was consistent with their own idea of what was going on (and based on the wrong target). Ugh! But this sort of thing goes on all the time. Only great diligence on the part of reviewers (and authors!) can prevent this, but, sigh, see number 3.

6. Publications in ‘top’ journals trump publications in ‘lesser’ journals. Maybe you knew this was coming. Someone publishes something interesting, really interesting, in a glossy journal, or one with nice soft pages. But, as it turns out, it’s just wrong. The ‘top’ journal isn’t particularly interested in publishing results that discredit their publication (which is getting lots of citations, see number 3). So researchers who can show that the work was misinterpreted, not reproducible, or just plain wrong submit to journals without the same impact factor, and sadly, without the same impact (these should not be the same thing). So while those working closely in the field know that the original paper was wrong, many who are in other fields (for whom the bad idea is nevertheless ‘useful,’ see number 5) and others who write reviews (see number 3) go with the work in the ‘top’ journal. I’m not saying that this is how it should be, but it is what it is.

7. There are other reasons people want the idea to stick around. Sadly, this is something we have to live with – not everyone is interested in what careful research has to tell us. Some of this relates to emotional investment, and some to alternative agendas. Examples of the first can be found in assertions that vaccines cause autism, or cell phones cause cancer – in the absence of a satisfactory explanation, people who are emotionally involved with a question will cling to any answer, regardless of its validity. For the second sort, economic consequences of findings are often offset by stringent adherence to discredited ideas. We know this, but it is sometimes startling how pervasive it is, and not only among non-scientists. Even scientists can have conflicts of interest (although in my case, they never add up to much moola – I’d love to have some real conflicts of interest. But I digress.) And perhaps the worst conflict of interest? If my ideas are proven wrong, I might have trouble getting my next grant, and thus difficulty maintaining my lifestyle, so I have a very vested interest in keeping my bad idea alive. I don’t me an ‘I’ of course, I mean ‘someone else,’ but I put this into the first person to be polite. Perhaps I should have said, “the vicious piranha, who doesn’t care about anyone but himself, has a vested interest.”

Okay, so that’s a few of the reasons why not all bad ideas don’t go away. What can we do about it? Hey, this is Mole here – you know I’m going to make some suggestions. But they may not be exactly what you expect. Are we going to burn down the house of bad ideas? Stay tuned.

(4 votes)

(4 votes)