A day in the life of…a mouse lab

Posted by Natalie Butterfield, on 11 October 2013

I work at the National Institute for Medical Research in London. My project is currently investigating the cues governing development of the limb, with an emphasis on cartilage patterning in vitro. I have a PhD in developmental biology and have been working with mice for over eleven years.

The mighty mouse.The mouse is a fantastic model system for several compelling reasons. They have a relatively short generation time, their genome is closely related to ours, and the potential for genetic investigation is virtually limitless. However, working with a protected model organism brings with it ethical and moral considerations, and of course means adhering to strict regulations set by the Home Office. This includes the rigorous application of the 3Rs (replace, reduce and refine), which involves only breeding the mice we need and being vigilant with our experimental design. We are lucky to have the help of trained technicians who cover a lot of the day-to-day maintenance of our colonies, including one long-suffering soul whose job is to process the genotyping of our colony on a weekly basis. Since being a researcher, I’ve done all of these tasks myself at some point or other, and while this gives you a great depth of knowledge, sometimes it’s exceptionally nice to have a helping hand.

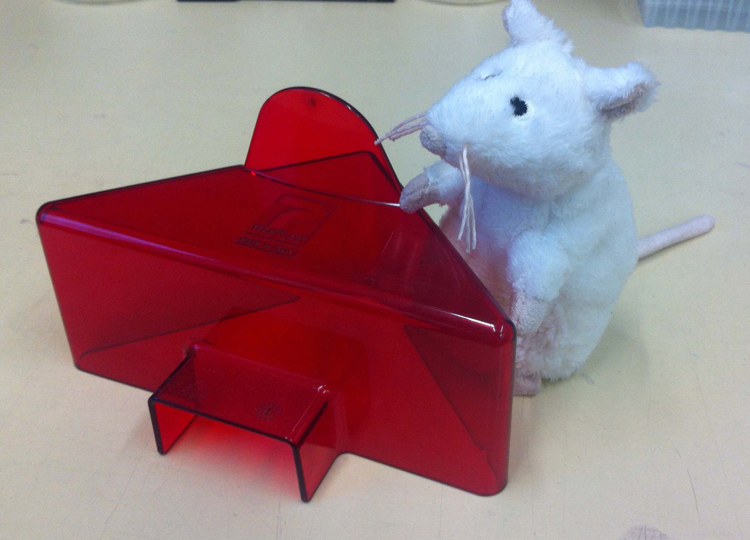

A bit about our furry friends. To get one mouse from another takes a relatively short 2 months, and gestation period is 19-21 days. Mice are born pink and hairless, deaf and with closed eyes, and require constant attention and feeding from their dam. However, they develop rapidly and are weaned at 3 weeks of age, by which time the pups are fully autonomous and extraordinarily energetic. A friend once coined the phrase ‘popcorn mice’ to describe the astonishing acrobatics a weaner mouse is capable of, which means that nothing sharpens the reflexes like handling weaners at the peak of their game. The litter will reach maturity less than a month after weaning (we breed our males at 8 weeks and females after 6-7 weeks). Our mice are supplied with cosy woodchip bedding with additional nesting material, a sterile cereal-based diet and a clean water supply, which can often put them ahead of our students in creature comforts. Since environmental enrichment is important for rodent wellbeing, each cage is also supplied with a little red house resembling a Lego toy to play and nest in, to which most mice will get exceedingly attached.

A bit about our furry friends. To get one mouse from another takes a relatively short 2 months, and gestation period is 19-21 days. Mice are born pink and hairless, deaf and with closed eyes, and require constant attention and feeding from their dam. However, they develop rapidly and are weaned at 3 weeks of age, by which time the pups are fully autonomous and extraordinarily energetic. A friend once coined the phrase ‘popcorn mice’ to describe the astonishing acrobatics a weaner mouse is capable of, which means that nothing sharpens the reflexes like handling weaners at the peak of their game. The litter will reach maturity less than a month after weaning (we breed our males at 8 weeks and females after 6-7 weeks). Our mice are supplied with cosy woodchip bedding with additional nesting material, a sterile cereal-based diet and a clean water supply, which can often put them ahead of our students in creature comforts. Since environmental enrichment is important for rodent wellbeing, each cage is also supplied with a little red house resembling a Lego toy to play and nest in, to which most mice will get exceedingly attached.

Genetics in the morning. As a developmental biologist, my research often focuses on the developmental processes occurring in the embryo prior to birth. For this it is necessary to obtain embryos by caesarean section. Depending on the stage I need, I usually dissect in the morning. For me, the optimal time point for this is between first and second cups of coffee, and after a banana (necessary and sufficient to minimise shaky hands). Dissections take place in specified rooms under low-power microscopes. Dissection can also be an oddly communal process, and some of the best chats are between researchers with their attention directed down their scopes. Genetically altered mice will need to be genotyped and while Mendel and his laws of inheritance allow us to predict genotypic ratios, it is not uncommon for these to be lower than expected. Sadly, this means Mendel comes in for a fair amount of abuse around genotyping time. Some of our lines also harbour fluorescent reporters, so we might also check the embryos under the appropriate filters to detect whether the designated tissue is fluorescing, which can be in a range of colours. As well as being very handy in an actual scientific way, this adds a pleasantly disco feel to the experiment.

Life in the mouse house. Our mice are housed in an exceptionally clean and secure animal facility, and for this reason there are strict barriers in place. My visit to the mouse house begins when I cross the barrier and play a version of not-allowed-to-touch-the-clean-floor to get to my rubber clogs. Clogs on, it’s time to perform a balancing act by changing into restfully green scrubs while keeping on said clogs. Each mouser completes their look with nitrile gloves, a hairnet and in some cases a facemask. Use of a facemask often requires diligent use of what supermodel Tyra Banks calls ‘smeyes’, those smiling eyes that are so essential if one wishes to avoid that dead-eyed look when communicating with other mousers.

Private lives. Once in the facility, my visit might include setting up breeding pairs to generate more mice. Getting to know the quirks of your model system can take a while. For example, females will conveniently cycle through heat, or oestrus, together if housed in the same cage and this can be triggered by adding a handful of the male’s bedding containing his pheromone-laden urine. This is called the Whitten effect, and is handy for when nothing less than a crowd of females in oestrus will do. It is also sometimes difficult to tell the difference between a pregnant mouse and a fat mouse, although some (very popular) users have developed the impressive skill of detecting early embryos by palpating the abdomen. Mice are highly sensitive to noise and smells, and the appearance of a new user, or even a new perfume can put some mice off their breeding.

Business time. Late afternoon is the time to take a final trip to the mouse house to set up an experimental cross to obtain embryos for future dissections. For these experiments, we need to know precisely when our mice have mated so we can count forward to obtain precisely staged embryos. Since mice are nocturnal, we bring our mating pair together in the same cage late in the afternoon. At 7pm the lights go out and Barry White is piped through the facility*. The lights come back on at 7am, completing the 24hr light-dark cycle and theoretically dampening any remaining ardour. During the morning the female is checked for evidence of mating (a waxy solid plug left in the relevant anatomical region by the male to discourage further mating) and the date will be recorded. This early morning pilgrimage to the mouse house to check matings remains one of the enduring memories of my Ph.D. These days though, the luxury of someone to do this for me means that someone else will check the mating for me in the morning, and this evening there is nothing more for me to do.

So as my day ends, life in the mouse house is beginning to wake up, ready for another night at the office. You could say that a day in the life of a mouse researcher is a night in life of a mouse, and alternative office hours aside, it’s a very productive collaboration indeed.

*Barry White may not actually be played in this facility

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

(8 votes)

(8 votes)

If you are enjoying our series on model organisms and would like to get involved, drop us an email! We are looking for people to write about a day in the life of the model organisms we haven’t covered yet!

We are looking for writers to cover both classical models and unusual critters- so do get in touch!

https://thenode.biologists.com/contact-us

Great story, specially enjoyed the last part on checking “plugs”. I use to do that for 8 years and now i changed my model (zebrafish) and sometime i miss our furry friends….