An interview with Rasa Elmentaite, the 2023 BSDB Beddington Medal winner

Posted by the Node, on 27 September 2023

The Beddington Medal is awarded by the British Society for Developmental Biology for the best PhD thesis in developmental biology, defended in the year prior to the award. The medal is named in memory of Rosa Beddington, who made major contributions to both the field of developmental biology and the BSDB. The artwork on the medal is from Rosa’s own drawings.

The 2023 Beddington Medal is awarded to Rasa Elmentaite. Rasa completed her PhD in SarahTeichmann’s lab at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. We caught up with Rasa over a cup of coffee in Cambridge to learn more about her background, her PhD work on the Gut Cell Atlas, and her future plans.

First of all, congratulations on receiving the 2023 Beddington medal! What does that this award mean to you?

It’s an amazing recognition, as developmental biology is a huge part of my PhD and the part that I most enjoyed thinking about. I find it incredible how studying developmental biology can help to not only understand how normal tissues form, but with the emergence of cell therapies, inform development of new disease treatments too. The award also means a lot to me personally, because I come from a small city, and I don’t have any scientists in the family. It means a lot when my family, my uncles and aunts messaged me saying, “wow you’re recognized!”

You mentioned coming from a small city, so let’s go back to the beginning. Where did you grow up?

I am from Lithuania. It’s a small, but culturally rich country with 3 million people. I grew up in a single parent household — it’s just me, my sister and my mom. My interest in sciences started when I followed my sister’s footsteps and got into one of the best schools in my city that is STEM oriented. My biology teacher was strict but also very engaging and she would always make sure we were the best of the best in biology and medical sciences. Perhaps that is the reason why half of my classmates became medics or scientists. My family also believes that in order to achieve something in life, one has to study very hard. Early on I followed this religiously.

How did you come to do a PhD at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute with Sarah Teichmann?

After school, I decided to go abroad and pursue an undergraduate degree at the University of Glasgow. This was a big deal for me, because I was the first one in my family to leave the country and study abroad. During my time in Glasgow, I sought out various internships during the summer holidays to gain hands on experience working in the lab. I worked in a neuroscience lab on pathways of pain and itch and later on I used Drosophila as a model system to study stem cells in the fly gut. Most of my lab experiences until that point had been on hypothesis-driven science. When I was applying for a PhD, I was intrigued by the Sanger Institute’s PhD programme. The institute uses an approach to science that I never experienced before — they generate a lot of data in order to form new and exciting hypotheses. I went from doing experiments in the lab and not knowing how to analyse data at all, to doing a PhD in a bioinformatics Institute. It felt like learning a different language.

In my first year at the Sanger PhD programme, I did three rotations. One of them was with Sarah Teichmann and Ludovic Vallier, who is an expert in stem cell biology and iPSC-derived cultures. My project involved doing single cell analysis together with Sarah Teichmann and her team on iPSC-derived gut organoids. I tried my best to make sense of the data that I generated during my rotation. By the end of my rotation, I still struggled to interpret cell type identities of these organoids, partly because there was no reference of what the normal gut cells look like. That’s how my PhD project came about. I decided to join Sarah Teichmann and the international Human Cell Atlas initiative that Sarah co-founded to create comprehensive maps of all the cells in the human body. My goal was to map the cells of the human gut and understand how their identities and organisation in tissues change from development to adulthood, and in diseases.

A large part of your PhD involved putting together the Gut Cell Atlas, which was published as a paper in 2021. Can you talk more about the work involved?

The idea of this project was to map single cells from different regions of the human gut at different timepoints from early development to adulthood. We didn’t have a specific hypothesis, but we wanted,amongst other questions, to know more about immunity in early life. We also wanted to map the gut in a comprehensive way so that the gut segments we collect reflect the regions where inflammatory diseases manifest.

A crucial part of the project was tissue access. We were very fortunate at the Sanger Institute to have access to organ donor tissues from Cambridge Biorepository for Translational medicine and foetal tissues from Human Developmental Biology Resource in Newcastle. We were also able to get samples from healthy children and children with inflammatory bowel disease through collaboration with Matthias Zilbauer in Cambridge. Some of these tissues came late at night, the surgeons were dedicated to retrieve them and provide them for research, which was critical for my PhD. I am very grateful for these efforts.

But it wasn’t just me — I was part of a large team. There were a lot of people involved, and without them, that project wouldn’t have happened. I had a lot of support from teams at Wellcome Sanger Institute who manage human tissue ethics and access, sample sequencing and colleagues in Teichmann, Zilbauer, Haniffa labs who helped with the protocol development, experimental design and data analysis. My PhD was truly a very unique experience that involved a lot of teamwork.

While this was exciting time in my PhD, it was also unusual at times. For example, I had to leave Cambridge for weeks and live in a hotel room in Newcastle in order to collect the samples on time ensuring that we generate good quality data. Logistics was difficult. I learnt that I much prefer the data analysis aspect of my project, because it involves asking scientific questions and with bioinformatics work it sometimes feels like the answers are at your fingertips.

Do you have a favourite piece of data/ insight from the Gut Cell Atlas?

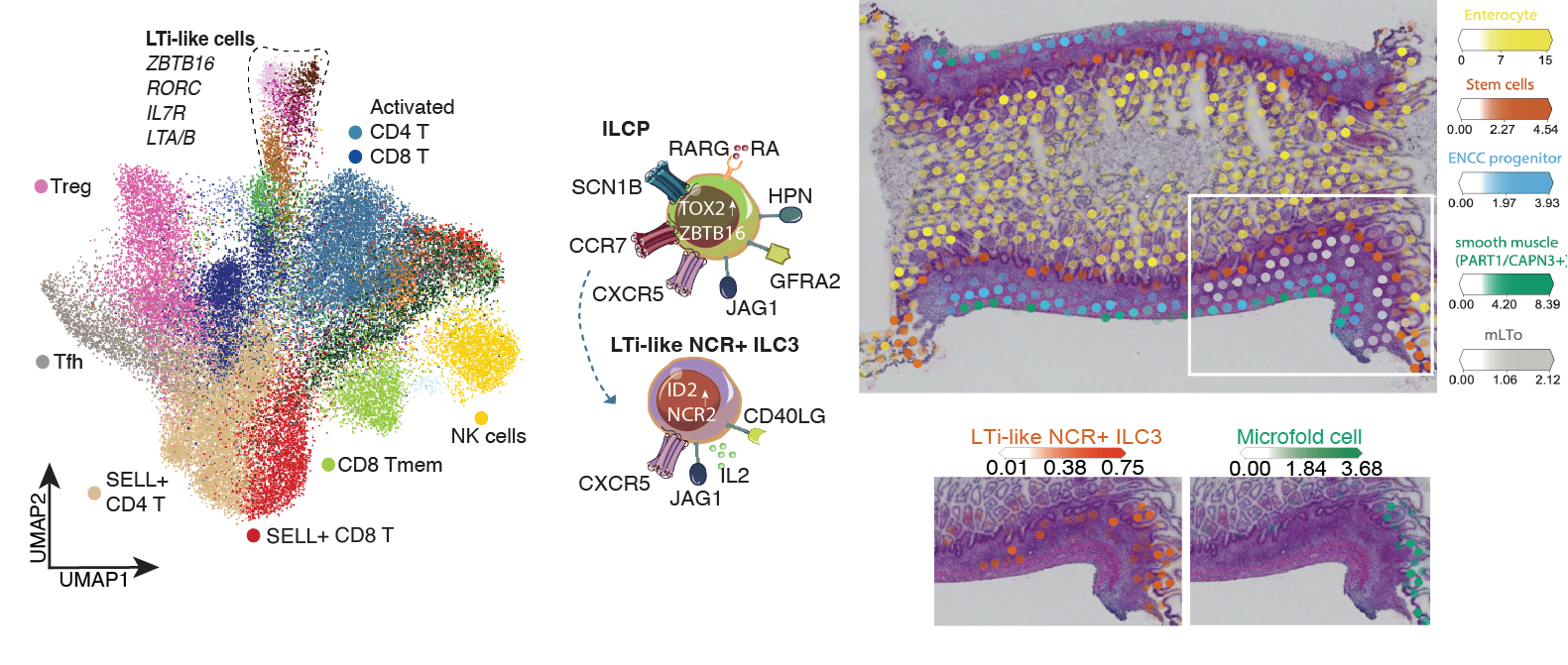

My favourite discovery relates to the formation of lymphoid tissues during human development. This intricate process involves three key cell types involved: lymphoid tissue initiator cells and two types of lymphoid tissue organiser cells. Understanding their interactions in developing human tissues is crucial for recruiting and retaining immune cells in lymph nodes and gut-associated lymphoid tissues – a process that is critical for development of normal immunity.

I recognised these cells in our atlas, because they have been characterised and studied previously in mouse models. Even still when I saw these cells in our Atlas, it felt like an accident because they are so rare in tissues. Even more exciting was that the organizer cells transcriptionally shared characteristics with the fibroblast cells we mapped in Crohn’s disease. I remember telling Sarah and our collaborator and immune development expert Muzz Haniffa about how these developmental programs could be working in disease to recruit immune cells during inflammation — maybe there is a way we can better understand disease through our developmental atlases. Then Muzz said, “I’m looking at exactly the same thing in psoriasis!” and I knew this is a discovery that is worth pursuing and understanding further.

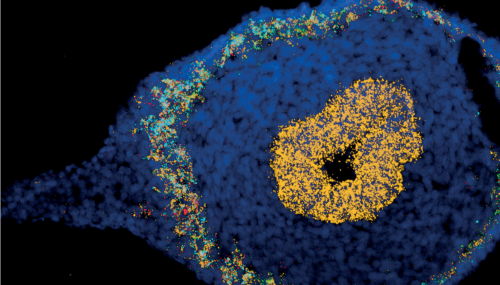

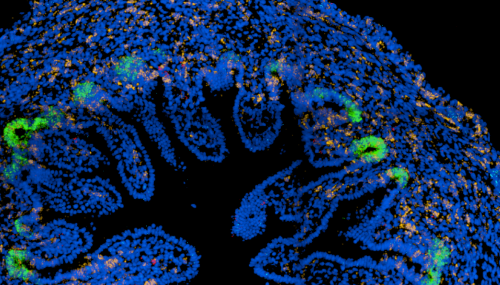

Rasa’s work on mapping the cells of the human developing gut contributed to better understanding of cellular and molecular mechanisms during enteric nervous system development and epithelial crypt-villus formation early in life. Fluorescent images show colonisation of the myenteric plexus by enteric neural progenitors (left) and emergence of intestinal stem cells (green, LGR5) in the human fetal intestine (right).

The Gut Cell Atlas work is part of a larger initiative called the Human Cell Atlas. What was it like being part of the initiative?

Within the consortium, every scientist brings their own expertise, from clinicians to biologists and data scientists. It feels like we’re all pieces of a puzzle and we come together to solve this complex problem of mapping cells. We share one goal — create a reference that can help future scientists to answer their own research questions. I think that’s something I’ll be very proud of in the future, and I already am, especially when other researchers tell me that they’ve used the Gut Cell Atlas and the data has helped them to answer their own scientific questions. Being part of the consortium also provides connection to other researchers who are working on similar questions. It generates a lot of enthusiasm, inspiration and provides a lot of support. It made me feel that even though we have a huge task in front of us, it is achievable if we work together.

Did you work on other projects during your PhD?

The culture at the Sanger Institute and the Teichmann laboratory is extremely collaborative. I was involved in multiple projects with members of Teichmann group, other groups at the Sanger Institute and also external collaborators. For most projects, I used my experience analysing single cell data to answer new and intriguing questions. For example, I worked on a project with collaborators in Oxford led by Holm Uhlig that aim to better understand how cells in the gut contribute to monogenic Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Another project focused on characterising enteroendocrine cell in an organoid system together with a team from Hans Clever’s laboratory. Even though the project only involved online interactions, it was a nice topic for me to work on because it brought me back to early days of my PhD, when I was trying to better understand organoid cells. It was much less frustrating this time round because now we had a reference to compare these organoid cells to!

There were also collaborations that were much less expected, like a project on Schwann cells. The gut has Schwann cells that migrate and colonize the gut during development and contribute to establishment of the enteric nervous system- so called second brain. A paediatric scientist, Sam Behjati, who is passionate about understanding childhood cancers was looking at the origins of neuroblastomas. We were interested in whether neuroblastoma cancers share similarities with some of the Schwann cells that we captured by profiling developing gut and adrenal glands. It was a very special project not only because of the translation impact of the project, but also because the lead author is a fellow Lithuanian Gerda Kildisiute and we had a great time working together.

Were there any frustrating moments during your PhD?

The one obvious frustration was the pandemic, which of course, affected everyone. There were already many challenges with the process of getting tissue access because the human samples are rare. When the pandemic hit, we couldn’t do any more experiments because the Institute’s focus, for good reason, shifted to better characterising and tracking the virus. The silver lining for me was that I could stay back home and focus on bioinformatic analysis of the vast amount of data that we generated. Nevertheless, during this time I missed the in-person interactions with members of our group. I feel these interactions and discussions were key for advancing scientific ideas during my PhD.

If you took one abiding memory with you from your PhD, what would it be?

There are a lot of joyful memories from my PhD, and it is challenging to pick one. I have great memories marking the day we learnt that our paper was accepted in Nature. I shared this moment with my colleague and mentor Kylie James and Sarah in her garden. It felt surreal. It was great to know that our data and insights into developmental and disease biology will have a broad reach. Personally, it also felt like a huge achievement and it was enabled by my supervisor’s willingness to give me independence, support and a feeling of trust that made me believe in myself. I think this is a key quality in a leader and something I aspire to carry over when I eventually have my own team.

Speaking of good supervisors, what do you think about the importance of having good mentors and supportive people around you?

Having female mentors and role models means a lot to me, and it extends beyond my PhD supervisor, to all my previous colleagues and mentors. I could relate so much more to them and it meant a lot to see that they are incredibly passionate at work and also have busy lives outside work. The achievements on my CV were only possible because the female leaders I had a chance to interact with. Starting with Sarah who has given me countless opportunities to present at the conferences, meet people in and outside academia and form unexpected collaborations. The lab members around me have also been very supportive and the supportive culture is propelled by the fact that everyone has their own experiences and expertise. We come together to interact and learn from each other. It’s never competitive.

What have you been working on since you completed your PhD? What’s next for you?

After my PhD, I sat down with Sarah to discuss what I could do next. I remember thinking I didn’t even know where to start looking for opportunities— should I stay in academia, transition to industry or try the start-up world? The opportunity came to co-found a start-up company together with Sarah as well as colleagues at Sanger Institute with expertise in the cell engineering field. I thought, it is now or never!

I decided to give myself one year to get the start-up going, which looking back was quite ambitious. During that year I worked as a staff scientist and dedicated my time to think about translational applications of the Human Cell Atlas data and computational tools that have been developed in the group. We started raising money on the idea of identifying drug targets using Human Cell Atlas data. The aim is to create a platform to better understand cellular and molecular mechanisms of disease and identify potential off-target toxicities through the Human Cell Atlas data. At the same time I also completed an internship with Foresite Capital, which gave me a unique perspective into the world of Venture Capital. These experiences and interactions exposed me to a different career path and greatly shaped my ideas on how to generate impact from the Human Cell Atlas research.

Longer term, do you know if you plan to stay in science?

I am a scientist at heart, and I think I’ll always stay in science in one way or another. For me it doesn’t really matter if I stay working in academia or pursue science in other ways. As long as I’m staying curious and creative about how I ask questions and interrogate the data in front of me, I consider myself a scientist.

Where do you think developmental biology will be in ten years? How do you think single-cell and spatial transcriptomics methods will advance in the next decade?

Single cell transcriptomics methods are increasing in resolution and becoming cheaper too. I am excited to see the day when we will be able to measure all the facets of a cell, including DNA, RNA, protein from a single cell as well as its spatial location in high throughput. Connecting this with gene and cell perturbations is going to be another step to better understand how cell identity is determined. It’ll be exciting to see how the data we generate will be combined with generative modeling and foundational AI. I am curious to see how this will improve the way the data is interpreted and what kind of insights we can get from it. I’m also excited about the developments in in vitro models and the way the field is advancing. There’s a lot of potential for understanding early human development through the lens of in vitro modelling and single cell genomics.

Outside of the lab, what do you like to do?

I enjoy trying new activities and generally staying active. Most weeks I enjoy bouldering, working out at the gym and I have also recently started cycling and running. On the days when I don’t want to be active, I design knitting projects – it is a hobby that I started during lockdown. Some people think it is an old-fashioned hobby, but for me it is an incredibly creative and rewarding activity because I get to make something entirely from scratch.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)