Postnatal neurodevelopment: Inside out or the reverse?

Posted by Xuanmao Chen, on 12 March 2025

The people behind the papers – Juan Yang and Xuanmao Chen

In mammalian embryos, brains develop from the inside out, with younger neurons moving to the outer layers in a process called radial migration. A new paper in Development finds that, during postnatal development, some of the neurons in the outer layers of the brain undergo a ‘reverse movement’, repositioning themselves by moving in the opposite direction to the initial radial migration. To learn more about the story behind the paper, we caught up with first author Juan Yang and corresponding author Xuanmao Chen, Associate Professor of Neurobiology at the University of New Hampshire (UNH), USA.

Xuanmao, what questions are your lab trying to answer?

Xuanmao: We pursue three major questions. First, we investigate how ciliary signalling modulates postnatal neurodevelopment and neuronal function, thereby influencing learning and memory formation. Second, we are intrigued by how a subset of excitatory neurons in the cerebral cortex are recruited to encode and store associative memory, and how a neuronal activity hierarchy in the brain is developed and maintained. Third, inspired by our recent progress, we seek to understand the evolutionary mechanisms, other than neurogenesis, that underly biological intelligence.

Juan, how did you come to work in the lab and what drives your research today?

Juan Yang: I first became interested in laboratory research during my undergraduate studies, particularly in my molecular biology class, where I was fascinated by how gene expression regulates organismal development and function. To pursue this interest, I joined the Hu lab at the Oilcrops Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, to study how the LAZY gene regulates branching angle formation in rapeseed. I spent countless hours performing PCR for plant genotyping but genuinely enjoyed working in the lab and felt a thrill every time I saw DNA bands appear on an electrophoresis gel. After graduation, I was fortunate to obtain a technician position in the Shen lab at ShanghaiTech University, China, where I became fascinated by using cutting-edge tools such as optogenetics and fibre photometry to investigate how specific neural circuits control the body’s homeostasis. These combined experiences sparked my passion for neuroscience and guided me to pursue my PhD dissertation research in the Chen lab at UNH, where I study neuronal primary cilia and cellular mechanisms underlying postnatal brain development.

What was known about neurodevelopment before you started the project?

Juan Yang & Xuanmao: It is well-established that pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex migrate from the neurogenic regions toward the cortical or hippocampal plate an inside-out manner. Before we started the project, we had thought that pyramidal neurons only undergo unidirectional migration, and the “terminal translocation” of radial migration is viewed as the final step for neuronal placement.

Can you give us the key results of the paper in a paragraph?

Juan Yang & Xuanmao: We discovered that primary cilia of early- and late-born principal neurons in compact layers in the mouse brain, such as the hippocampus CA1 region, display opposite orientations, while primary cilia of principal neurons in loose laminae, including the subiculum, entorhinal cortex, neocortex, and cingulate cortex, are predominantly oriented toward the pia. However, specific cilia directionality was not observed in astrocytes and interneurons in the cerebral cortex, or neurons in nucleated brain regions. Guided by this clue, we found that the cell bodies of principal neurons in inside-out laminated regions, including the hippocampal CA1 region and the neocortex, undergo a slow “reverse movement” for postnatal positioning. Our evidence indicates that it is the reverse movement during early postnatal development that leads to the primary cilia of pyramidal neurons to predominately orient toward the pia. Therefore, the “terminaltranslocation” of radial migration is not the last step, pyramidal neurons in the postnatal cerebral cortex continue to adjust their position and move inwards. The reverse movement must be important for constructing sparsely layered inside-out laminae and for forming sulci (grooves) in the mammalian brain.

Why did you decide to focus on primary cilia?

Xuanmao: I initially studied type 3 adenylyl cyclase (AC3) during my postdoc training in the Storm Lab at the University of Washington, USA. AC3 is a cilia-specific cyclase originally identified in olfactory cilia. AC3 is known to be essential for olfactory perception in mammals. My first project was to study the role of AC3 in airflow-mediated mechanosensation of olfactory cilia (Chen et al., 2012). Cilia dysfunction is associated with numerous brain disorders in humans, and AC3 was found to be highly enriched in neuronal primary cilia throughout the brain (Bishop et al., 2007). However, the functions of AC3 and neuronal primary cilia in the brain are largely unknown (Guemez-Gamboa et al., 2014). The significance of these unanswered questions prompted me to study neuronal primary cilia in the central nervous system. Years later, it is the intriguing cilia directionality of pyramidal neurons marked by an AC3 antibody that guided the lab to make a breakthrough in the context of postnatal neurodevelopment.

What implications does your work have for understanding human brain evolution?

Xuanmao: In my opinion,the mammalian cerebral cortex, particularly the primate neocortex, can be likened to a “library” consisting of numerous shelves and layers of “books” (excitatory principal neurons). The development of such a sparsely layered, matrix-like architecture and its evolution from the allocortices of lower vertebrates (amphibians or reptiles) to the neocortex of humans not only involves increased neurogenesis (Florio and Huttner, 2014; Rakic, 2009; Taverna et al., 2014) and sufficient accommodating space but also requires fast, long-distance neuronal migration (Nadarajah et al., 2001) and slow, fine-tuned repositioning for final neuronal placement. These processes, particularly the slow repositioning step, permit orderly neuronal maturation and progressive circuit formation, and allow the brain to acquire external information during postnatal development to gradually construct well-organized neural circuitry to enable efficient information processing, storage and retrieval.

Upon the completion of fast radial migration, the outer layer in the cerebral cortex is highly condensed. It is unclear how the mammalian neocortical structures gradually become loosely layered, while allocortical regions remain highly compact. I believe that an additional step of reverse movement is needed for constructing the sparse 6-layered neocortex. Without reverse movement, only tightly compact 3-layered laminae can be made. Without reverse movement, neuronal maturation in the hippocampal CA1 and neocortex might occur simultaneously (as occurs in the CA3 region)(Yang et al., 2024), rather than following a sequential pattern. Therefore, the reverse movement of pyramidal neurons must be crucial for the evolutionary transition from the 3-layer allocortex to 6-layer neocortex. It is also linked to the gyrification process in gyrencephalic animals, because we discovered that a sulcus is formed, at least in part, via reverse movement.

When doing the research, did you have any particular result or eureka moment that has stuck with you?

Juan Yang & Xuanmao: The Chen lab has been intrigued by the directionality of primary cilia for many years, having observed interesting cilia orientation patterns in multiple peripheral tissues and many cortical regions. We noticed a striking alignment of cilia in the mouse hippocampus at postnatal day 14 (P14), with most pointing in the same direction. However, within the thin stratum pyramidale (SP) of the CA1 region, we observed a small subset of cilia oriented in the opposite direction. This orientation pattern was absent at other developmental stages. We did not know how to interpret this phenomenon, and the question lingered in our minds for several years. One day at home, while casually browsing hippocampus-related articles, Juan Yang came across a review article by Soltesz and Losonczy (Soltesz and Losonczy, 2018), from which she learned that the hippocampal SP contains two distinct neuronal populations: early-born and late-born neurons. This paper inspired her to speculate that the opposing cilia orientations in the CA1 SP likely belong to two distinct groups of neurons. Yang then sent the review paper to Chen in an email explaining her hypothesis. After reading the review paper a few days later, Chen responded: “That makes sense and let’s verify it”. This was the first eureka moment in advancing our understanding on cilia directionality.

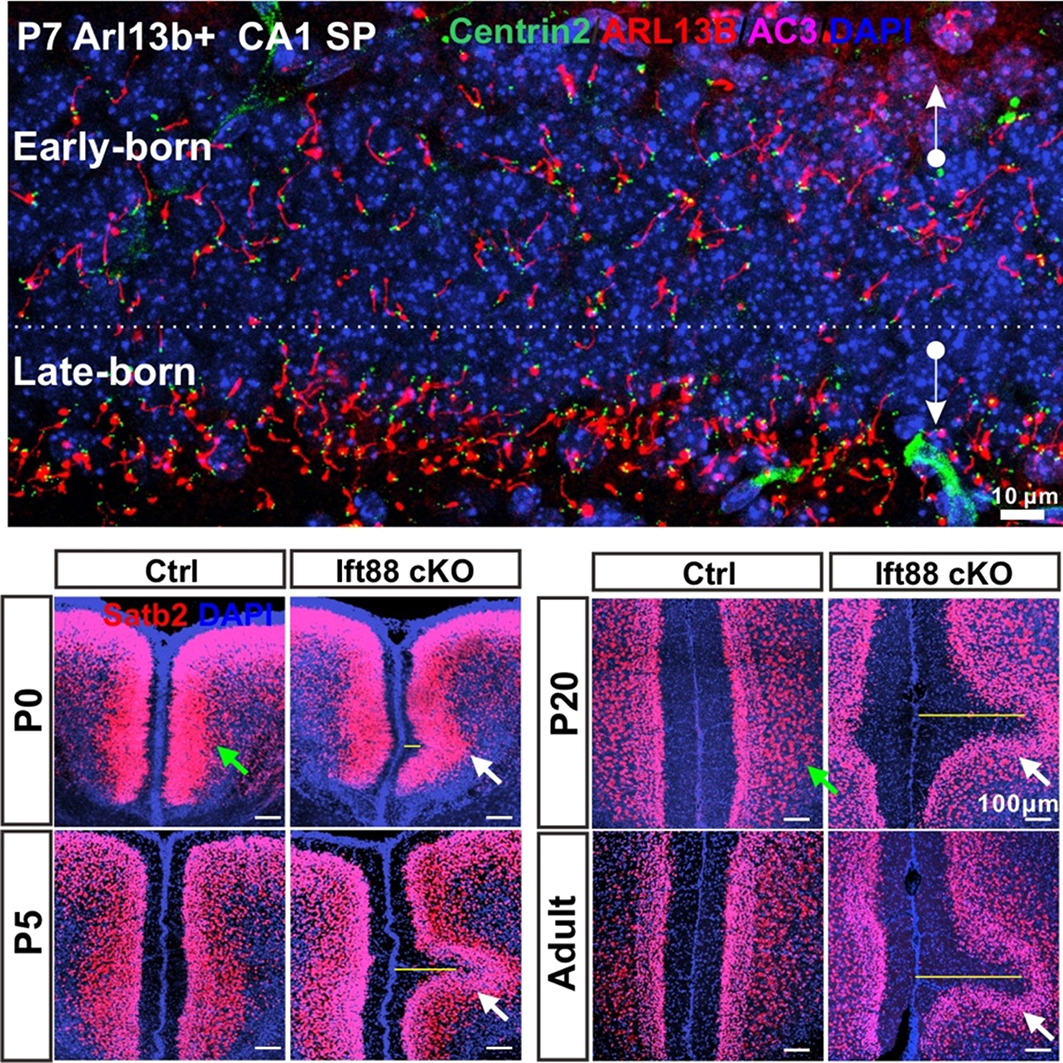

The concept of reverse movement could not have been developed if the lab had only used wild-type (WT) mice to assess cilia orientations. In the WT hippocampal CA1 region, the primary cilia of pyramidal neurons are not very long (5-8 µm), and they protrude out of the plasma membrane within a short two-day window (P9–P11), by which point centrioles are no longer clustered at the bottom edge of the SP. Fortunately, the lab also maintained Arl13b-mCherry, Centrin2-GFP double transgenic (Arl13b+) mice (Bangs et al., 2015; Higginbotham et al., 2004), which mark primary cilia and centrioles, respectively. The transgenic mice have much longer cilia (~16 µm) in the CA1 region than the WT mice. They also express cilia a few days earlier than WTs and have a prolonged ciliation time-window spanning from P3 to P14. This extended period provided us with more snapshots to track the cilia and centriole positioning process as well as cell body movement during early postnatal development. For example, at P7 in Arl13b+ mice, early-born neurons have already emanated long cilia, which are largely oriented toward the stratum oriens (SO), whereas late-born neurons are only just beginning to protrude cilia, which are enriched in the bottom edge of the SP and orient toward the stratum radiatum (SR) (Figure 1, top panel). This striking contrast instantly led Chen to formulate a concept of reverse movement, in which late-born neurons first migrate to the bottom edge of the SP before moving back to the main part of the SP. Recognizing the existence of this reverse process was the second key step in advancing this research. Subsequently, we found that slow reverse movement is a common positioning step for most of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex.

The lab also housed a Ift88 conditional knockout (KO) mouse strain (Haycraft et al., 2007), which lacks primary cilia on the excitatory neurons and astrocytes in the forebrain. Notably, Ift88 cKO mice produce a lot more late-born neurons than WTs. The overcrowding of late-born neurons in the outermost cortical layer of Ift88 cKOs gradually leads to the formation of a sulcus via a reverse movement (Figure 1, bottom panel). This observation indicates that principal neurons are subject to backward movement for postnatal repositioning, sometimes individually if the outermost layer is not very crowded, and sometimes collectively if too crowded.

And what about the flipside: any moments of frustration or despair?

Juan Yang: The challenges of scientific research are numerous, but for me, they gradually fade away – either forgotten over time or overshadowed by new research progress and gaining recognition from my peers.

Why did you choose to submit this paper to Development?

Juan Yang & Xuanmao: Development has a long-standing reputation as a leading peer-reviewed scientific journal focused on developmental biology. We rely on the editorial board’s expertise in neurodevelopment and professionalism to evaluate the significance of our discoveries.

Where will this story take your lab next?

Xuanmao: This story opens multiple new avenues to explore. The lab is well positioned to address the following questions: (1) what key factors control cilia directionality and the reverse movement of principal neurons, and consequently neuronal maturation; (2) how primary cilia regulate or stabilize neuronal positioning; (3) how reverse movement impacts the cortical evolution of mammals; and (4) how neuronal primary cilia modulate neuronal function, contributing to associative learning and memory formation.

Finally, let’s move outside the lab – what do you like to do in your spare time?

Juan Yang: I enjoy playing table games, exploring new cuisines and traveling.

Xuanmao: In the summer, I enjoy spending time with friends and family, swimming and paddling on lakes and beaches. Fall is my favourite time for hiking and admiring the vibrant maple leaves in the mountains. In winter, I love skiing with the kids. The most rewarding activity in my spare time is thinking freely without set objectives and sketching on whiteboards – a hobby that I call “whiteboard fun”.

References:

Bangs, F.K., N. Schrode, A.K. Hadjantonakis, and K.V. Anderson. 2015. Lineage specificity of primary cilia in the mouse embryo. Nat Cell Biol. 17:113-122.

Bishop, G.A., N.F. Berbari, J. Lewis, and K. Mykytyn. 2007. Type III adenylyl cyclase localizes to primary cilia throughout the adult mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 505:562-571.

Chen, X., Z. Xia, and D.R. Storm. 2012. Stimulation of electro-olfactogram responses in the main olfactory epithelia by airflow depends on the type 3 adenylyl cyclase. J Neurosci. 32:15769-15778.

Florio, M., and W.B. Huttner. 2014. Neural progenitors, neurogenesis and the evolution of the neocortex. Development. 141:2182-2194.

Guemez-Gamboa, A., N.G. Coufal, and J.G. Gleeson. 2014. Primary cilia in the developing and mature brain. Neuron. 82:511-521.

Haycraft, C.J., Q. Zhang, B. Song, W.S. Jackson, P.J. Detloff, R. Serra, and B.K. Yoder. 2007. Intraflagellar transport is essential for endochondral bone formation. Development. 134:307-316.

Higginbotham, H., S. Bielas, T. Tanaka, and J.G. Gleeson. 2004. Transgenic mouse line with green-fluorescent protein-labeled Centrin 2 allows visualization of the centrosome in living cells. Transgenic Res. 13:155-164.

Nadarajah, B., J.E. Brunstrom, J. Grutzendler, R.O. Wong, and A.L. Pearlman. 2001. Two modes of radial migration in early development of the cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. 4:143-150.

Rakic, P. 2009. Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 10:724-735.

Soltesz, I., and A. Losonczy. 2018. CA1 pyramidal cell diversity enabling parallel information processing in the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 21:484-493.

Taverna, E., M. Gotz, and W.B. Huttner. 2014. The cell biology of neurogenesis: toward an understanding of the development and evolution of the neocortex. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 30:465-502.

Yang, J., S. Mirhosseiniardakani, L. Qiu, K. Bicja, A. Del Greco, K. Lin, M. Lyon, and X. Chen. 2024. Cilia Directionality Reveals a Slow Reverse Movement of Principal Neurons for Postnatal Positioning and Lamina Refinement in the Cerebral Cortex. BioRxiv 473383v7.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)