A planarian’s journey from Sardinia to the Midwest

Posted by Tracy Chong, on 22 February 2012

In 1999, twenty-nine planarians, courtesy of Dr. Maria Pala made the journey across the Atlantic from the beautiful mediterranean island of Sardinia, to Baltimore, Maryland, into the hands of my advisor, Phil Newmark, who was then a post-doctoral fellow in Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado’s laboratory at the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

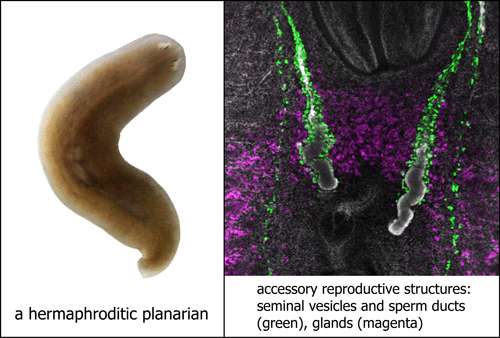

Realizing the potential of the flatworms he held in his hands, he took advantage of their power of regeneration and cut them into many pieces, each of which grew into a whole new animal. In this way, he generated clonal lines of the sexual strain of the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. These animals are simultaneous hermaphrodites- meaning that they have functional male and female reproductive organs; unlike C. elegans, they are not self-fertile and must mate to propagate. Inbred lines were derived in the Sánchez Alvarado lab from one of the clones and used for sequencing the S. mediterranea genome.

When I joined the Newmark lab at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I was fascinated by the developmental plasticity of these planarians. Due to a population of stem cells called neoblasts, they can grow and degrow, and their reproductive system can regress and regrow depending on environmental factors. Even more amazing, these flatworms could regenerate their whole reproductive system, including the germ line, from fragments that were initially devoid of reproductive tissue. Understanding the mechanisms that the planarians use to achieve this feat is one of the main themes of research in the Newmark Lab.

Interestingly, there is a strain of S. mediterranea that reproduces asexually by transverse fission. The existence of two divergent modes of reproduction in a single species presents a unique opportunity to identify conserved and species-specific genes that are important for germ cell development and reproductive system maturation.

Together with my colleagues, Yuying Wang and Joel Stary, we performed microarray analyses to identify genes that are expressed differentially between the asexual and sexual planarians; we then used in situ hybridization to examine the cell types in which these genes were expressed. To complement this transcriptomic approach, we also identified several antibodies and fluorescent lectin-conjugates that labeled components of the planarian reproductive system.

This work, as presented in our BMC Developmental Biology paper, provides markers and tools to further characterize the hermaphroditic reproductive system of S. mediterranea. I was thrilled to see that there were genes specific to either male or female components of the reproductive system, suggesting sex-specific mechanisms in a simultaneous hermaphrodite. I am very excited to unravel the mystery of how these hermaphroditic worms are able to develop both male and female parts. With their genome now experimentally accessible, little did the twenty-nine planarians know how they would contribute to science when they made their journey across the Atlantic 13 years ago.

(11 votes)

(11 votes)