First issues – breaking newt

Posted by Laura Hankins, on 12 February 2025

As part of our ‘first issues’ series to mark The Company of Biologists’ 100th anniversary, Development’s in-house team are researching the authors of articles published in the first issues of the Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology (JEEM) and its reincarnation, Development. In this post, we meet Ruth Clayton, a biologist who worked at the University of Edinburgh and who published an article in the first issue of JEEM.

Ruth Clayton was born in London in 1925 [1], the same year that our publisher, The Company of Biologists, was founded. Since Clayton would have turned 100 this year, it feels appropriate to honour her as part of the Company’s own 100th birthday celebrations. Clayton studied Zoology at Oxford before moving to the Institute of Animal Genetics (IAG) at the University of Edinburgh. Interestingly, this links Clayton to The Company of Biologists, since the IAG was initially established as the Department of Research in Animal Breeding by Francis Crew, who happens to have been the Managing Editor of our sister journal, Journal of Experimental Biology (JEB). I found out a bit about Crew and the institute a couple of years ago when researching the authors from JEB’s first issue [2]. The journal, which was founded in 1923 as the British Journal of Experimental Biology, quickly ran into financial difficulties, and George Parker Bidder III founded The Company of Biologists to safeguard its future [3].

By the time Clayton joined the IAG, it had come under the leadership of C. H. Waddington. Waddington is of course best known for his iconic epigenetic landscape [4], but he was also a member of JEEM’s first Editorial Board [5]. Clayton helped produce a gift for Waddington’s 50th birthday: a commemorative photo album [6]. This is worth a mention, mostly because it features candid shots of other IAG researchers [7] including Charlotte Auerbach and Tom Elsdale (who we’ll hear about on Friday, in the final post of this series), but also because the album documents the institute’s “Drosophila ballet”, which looks just as bizarre as it sounds [8]. The photo album was presented to Waddington at his birthday party, which seems to have been a similarly eccentric event, apparently featuring a pinball machine modelled on Waddington’s landscape [9]. Sadly, I could not find photographic evidence of the original machine, but during my search I did stumble across a paper that redraws Waddington’s epigenetic landscape as a pinball machine [10; the idea seems to be that the machine’s flippers can promote dedifferentiation]. So, maybe the party organisers were onto something.

Clayton’s article in JEEM’s first issue focuses on antigen specificity in the alpine newt (Triturus alpestris) embryo [11]. She begins her paper with a statement that still rings true for developmental biologists over 70 years later: “The mechanism of differentiation presents one of the central problems of embryology.” Clayton’s study aimed to address one aspect of this problem by investigating how antigens in the early embryo differ from those in the adult, to give hints as to what changes during the process of differentiation. To do this, she dissected different sections of newt embryos (e.g. ectoderm, mesoderm and tailbud) at different stages (e.g. blastula, gastrula) and homogenised them for injection into rabbits, to produce antisera.

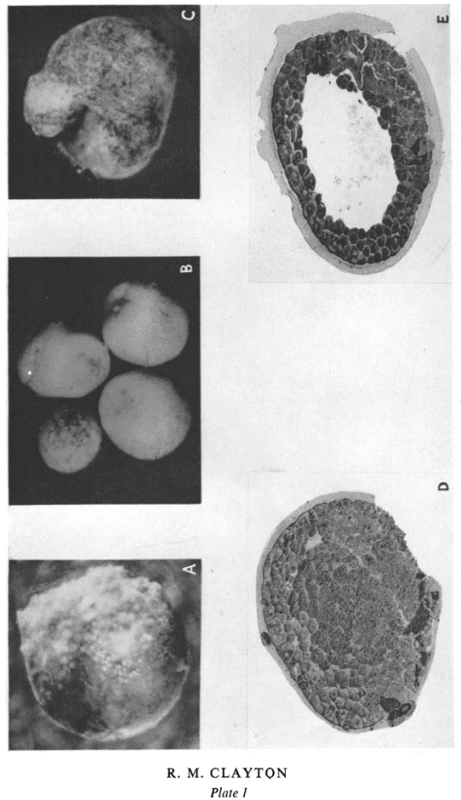

The use of antisera in biology goes back a remarkably long way; at the turn of the 20th century, Emil von Behring pioneered ‘serum therapy’, injecting mammals including guinea pigs with diphtheria and tetanus toxins and ultimately using the resulting antiserum to treat patients [12, 13]. Nowadays, developmental biologists might be most familiar with using antibodies for Western blots, or for immunostaining. In her paper, Clayton mixed the antisera and antigens produced from different embryonic structures and recorded whether they cross-reacted. She went on to test the effects of placing embryos (Fig. 1) and explants in sera, antisera or absorbed antisera (i.e. the antigen and antisera mixes from earlier in the paper). The results are all a bit of a puzzle to tease out, because the experiments are done in multiple combinations, but they allow Clayton to deduce the existence of common antigens (which are present throughout development) and antigen fractions that arise at specific timepoints. For example, she notes that blastulae die or exhibit perturbed development when placed in “anti-gastrula serum absorbed with blastula” and suggests that this “is due to antibodies left in the medium after removal of antibodies to blastula antigens, i.e. that at gastrulation a new fraction appears”.

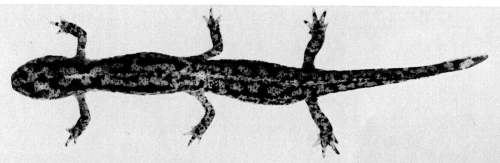

Clayton explains that she chose to work with the alpine newt for a couple of reasons: she needed “an embryo whose dissection might prove relatively easy and large numbers of which were available”. Today, other salamander species, such as the axolotl, are widely used to study regeneration. By contrast, the alpine newt doesn’t seem to have endured in developmental biology research. Indeed, a very quick search of Development’s archives suggests that it’s been nearly 50 years since we last published a research paper about alpine newts (to be fair, it’s a memorable article, featuring a chimeric newt with six legs (Fig. 2, 14). However, there is evidence that JEEM used to feature a pleasing range of newt species, including the California newt [15], the Iberian ribbed newt [16] and the Japanese fire-bellied newt [17]. Clayton’s rationale is a reminder of the importance of selecting the most appropriate organism to address a particular research question, so maybe the alpine newt will make a comeback when the circumstances are right. We highlighted the use of unconventional model organisms in our 2024 Special Issue [18].

Clayton published in JEEM a total of four times. She continued to make use of antisera in her investigations, but her subsequent work focused on cell differentiation in the context of the developing chick eye. This included research into the transdifferentiation of neural retina cells into pigment and lens cells [19]. Today, transdifferentiation is an active area of research that may hold promise for stem cell-based therapies. Clayton remained at the IAG, where Waddington later won funding to establish an Epigenetics Research Group. However, according to an obituary written by Alan Robertson, much of the project’s resources were used for molecular biology research that had no clear implications for development [9]. Indeed, Robertson mentions Clayton as “a notable exception” whose work on avian lens development “fitted into Waddington’s original concept”. Later in her career, Clayton’s expertise in lens development saw her lead an interdisciplinary collaboration to investigate risk factors for cataract formation [1]. She retired in 1993 and was appointed Reader Emeritus. Clayton’s obituary was published in the University of Edinburgh’s eBulletin in February 2003. It states that “though never formally a Director of Studies, she was often the member of staff to whom students turned for guidance”, suggesting that she was a dedicated mentor as well as a great scientist.

References

[1] Staff news pre-2009. eBulletin Archive. February 2003. Obituaries. Ruth Clayton. https://www.ed.ac.uk/news/staff/archive [accessed 21/01/2025]

[2] Hankins, L. E. and Rutledge, C. E. (2023) Class of 1923: looking back at the authors of JEB’s first issue. J Exp Biol; 226 (1): jeb245424. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.245424

[3] Knight, K. (2023) Journey through the history of Journal of Experimental Biology: a timeline. J Exp Biol; 226 (22): jeb246868. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.246868

[4] Waddington, C.H. (1957). The Strategy of the Genes (1st ed.). Routledge. doi: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315765471

[5] Eve, A. (2025) Development: a journal’s journey. Development; 152 (3): dev204602. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.204602

[6] https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/archival_objects/17322 [accessed 21/01/2025]

[8] https://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/towardsdolly/2014/03/24/picture-perfect/ [accessed 21/01/2025]

[9] Robertson, A. (1977) Conrad Hal Waddington, 8 November 1905-26 September 1975. Biogr. Mems Fell. R. Soc; 23, 575–622. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbm.1977.0022

[10] Sareen, D. and Svendsen, C.N. (2010) Stem cell biologists sure play a mean pinball. Nature biotechnology; 28(4), 333-335. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0410-333

[11] Clayton, R. M. (1953) Distribution of Antigens in the Developing Newt Embryo. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology; 1 (1): 25–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.1.1.25

[12] Behring, E. V. (1890) Ueber das zustandekommen der diphtherie-immunität und der tetanus-immunität bei thieren. Dt. Med. Wochenschr; 49, 1113–1114.

[13] Behring, E. V. (1913) Ueber ein neues Diphtherieschutzmittel. Dt. Med. Wochenschr; 39: 873-876.

[14] Houillon, C. (1977) Tractus uro-génital des chimères chez l’amphibien modèle Triturus alpestris Laur. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology; 42 (1): 15–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.42.1.15

[15] Tucker, R. P. and Erickson, C. A. (1986) The control of pigment cell pattern formation in the California newt, Taricha torosa. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology; 97 (1): 141–168. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.97.1.141

[16] Deparis, P. and Jaylet, A. (1984) The role of endoderm in blood cell ontogeny in the newt Pleurodeles waltl. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology; 81 (1): 37–47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.81.1.37

[17] Matsuda, M. (1980) Cell surface properties of amphibian embryonic cells. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology; 60 (1): 163–171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.60.1.163

[18] Extavour, C., Dolan, L., Sears, K. E. (2024) Promoting developmental diversity in a changing world. Development; 151 (20): dev204442. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.204442

[19] De Pomerai, D. I. and Clayton, R. M. (1978) Influence of embryonic stage on the transdifferentiation of chick neural retina cells in culture. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology; 47 (1): 179–193. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.47.1.179

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)