Greetings from the 118th Embryology Class

Posted by David Gold, on 6 July 2011

Twenty-four of us have been working for the past five weeks, studying development in a variety of contexts and organisms at the Marine Biology Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. The area is beautiful, but we don’t have much time to enjoy it. This is a very intense course, we have lectures from 9am to noon, and then work on experiments often until 1 or 2 in the morning! Because of this, we have been a little slow getting our blogposts going, but we look forward to sharing our experiences from Woods Hole.

Our course directors, Nipam Patel and Lee Niswander, presented the Embryology course as a chance to work with the latest techniques on model organisms (such as mice, and fruit flies), while providing a broad introduction to the diversity of animal evolution. The first two weeks of the course exemplified these dual goals, as we studied some of the earliest branching animal lineages, and the two major invertebrate model systems.

At the beginning of the course Nicole King came to teach us how to work with choanoflagellates and sponges, while Uli Technau introduced us to the cnidarians (in particular the sea anemone Nematostella and the hydrozoan Hydractinia). Sponges and cnidarians are morphologically much simpler than most animals, and genetic evidence supports the long-standing hypothesis that they were some of the first groups to diverge from our own lineage. However, sponges and cnidarians possess many of the genes “higher” animals have, and they have provided important insight into the ways cells communicate during development.

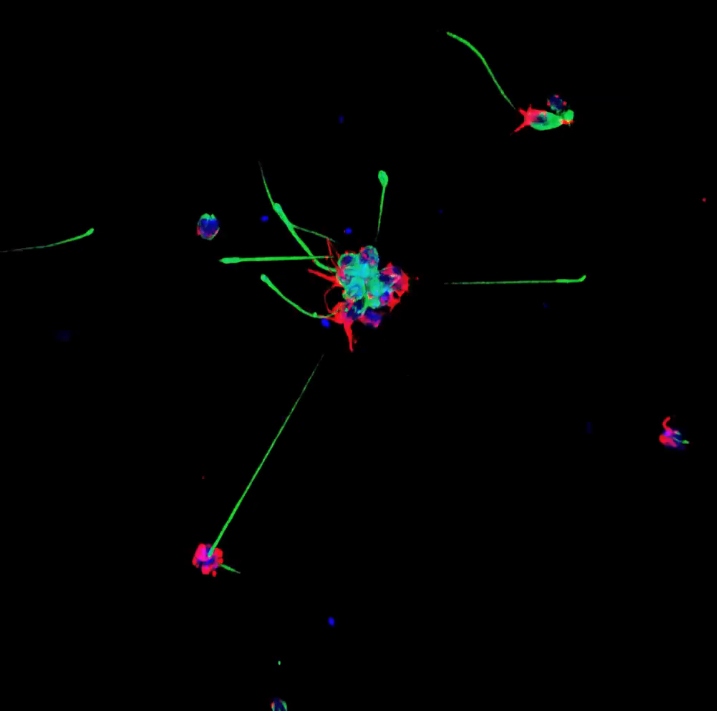

Choanoflagellates are not actually animals, but DNA evidence suggests that they may be animals’ closest living relatives. Each choanoflagellate is a single cell. It has a long flagellum, which it uses to swim through the water and to trap bacteria (which it eats) in a collar made up of microvilli. The reason that choanoflagellates have received a lot of attention recently is that they don’t always spend life as a single cells. Sometimes, as a choanoflagellate divides, the individuals stay connected to each other in long chains or rosettes. Perhaps these organisms can teach us how the first multicellular animals evolved. Below is an image created by classmate Valerie Virta showing single and colonial choanoflagellates, the blue is staining the choanoflagellate bodies (DAPI), the red is microvillar collar (actin) , and the green is the flagellum (tubulin):

A team of scientists, including Joel Rothman, Dave Sherwood, and David Fitch, then came to teach us about the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans. C. elegans has become a important model for understanding basic development. Dave Sheerwood, for example, gave a great lecture on how the developing vulva of C. elegans may provide a better model for studying cancer than cultures of human tissues (you can find a podcast about his work here; look for the podcast from 5/10/10).

Finally, we got our hands on the invertebrate workhorse of genetics and developmental biology, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. It’s exiting to think that Thomas Hunt Morgan, the Nobel Prize winning founder of fruit fly genetics, did much of his research at the same institute we are working at now. Nipam Patel, Lynn Cooley, Iswar Hariharan, and Matt Ronshaugen showed us a number of techniques for visualizing development, gene expression, and miRNA exoression in D. melanogaster, as well as how those techniques could be modified to look at other arthropods. Below is a movie taken by David Gold of several Drosophila imaginal disks, stained with eyeless, cubitus interruptus, teashirt, and dapi:

We look forward to updating you with details about the third and fourth weeks soon. More detailed posts will be available over time from David Gold’s blog at www.BioBlueprints.com.

(7 votes)

(7 votes)

Thanks for the update! Choanoflagellates sound (and look!) very intriguing.

I’ve also embedded your fly video so it’s easier to watch from here rather than clicking through. Hope that’s okay =)