On the beauty and wonder of endless forms: a reflection on Embryology Course 2018

Posted by Paul Gerald Layague Sanchez, on 16 August 2018

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

– Charles Darwin

I spent the summer of 2018 at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, US as a student in the Embryology Course. Here, I will reflect on what was a very transformative experience, and while doing so, I would like to share my insights on the beauty and wonder of diversity in developmental biology.

Prior to coming to Woods Hole, my understanding of developmental biology was limited. I studied biochemistry as an undergrad in the Philippines and trained as a chemist. I was not formally exposed to developmental biology research until recently, when I started my PhD in Alexander Aulehla’s Lab at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in 2016. The desire to broaden my knowledge of underlying principles, mechanisms, and processes in animal development prompted me to attend the Embryology Course this year.

During the Embryology Course, I was introduced to at least a hundred different animal species, spanning both classical and emerging models of development. I worked on organisms beyond what I imagined. I got the chance to learn about and do experiments on several animals like sea squirts and sea urchins, ctenophores and tardigrades, shrimps and snails, and annelids and flatworms. I was fascinated by how the left-right asymmetry of sea squirt embryos significantly relies on its rotation during embryogenesis, and mesmerized by the symmetry and patterning of the skeleton of the pluteus larva of sea urchins. I was enthused by the coordinated beating of cilia on ctenophores, and excited by the unique cleavage pattern of tardigrade embryos. I was astonished by the differences in segmentation in the dorsal and ventral axes of Triops, a freshwater shrimp, and captivated by the establishment of chirality of the shells of snails. I was thrilled by how Pectinaria, a marine annelid, builds its home from grains of sand, and amazed by the regenerative capacity of flatworms like planaria.

ON THE BEAUTY AND WONDER OF DIVERSE EMBRYOS

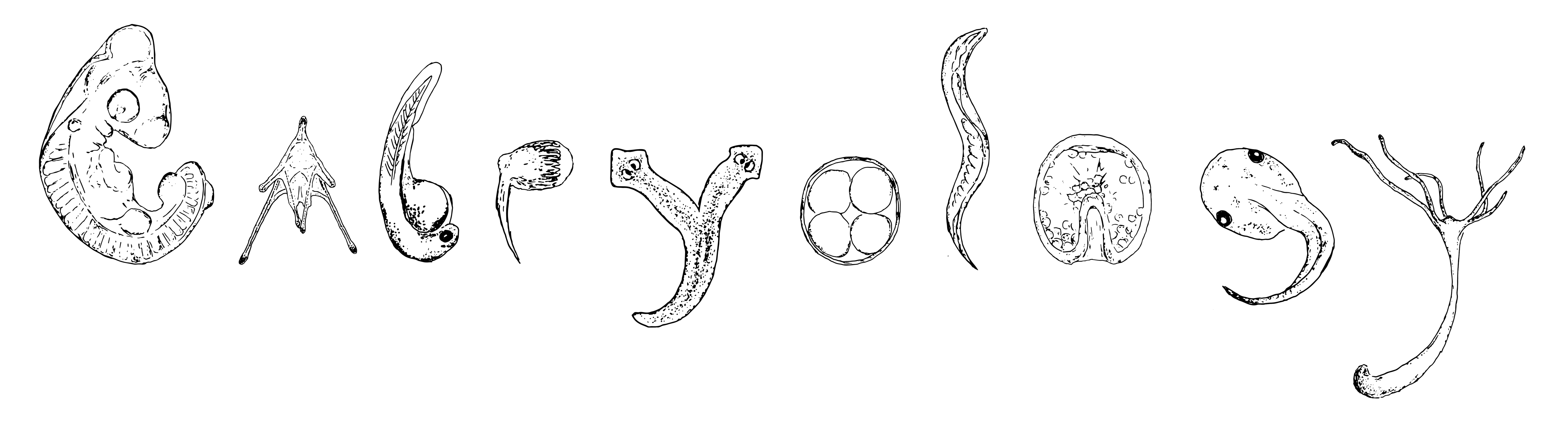

An illustration of some of the organisms we worked on during the course, arranged to spell EMBRYOLOGY.

We used this for our banner during the July 4th Parade and also printed it on our batch T-shirt.

Illustration by: Ashley Rasys

Integral to studying embryogenesis and animal diversity, the Embryology Course highlighted the strength of comparative embryology in furthering our grasp of unifying principles in development. For instance, the establishment of diverse body plans was a recurring theme throughout the course. It is fascinating how the same toolkit, a set of genes known as Hox genes, lay down the blueprint in patterning the body of very different animals like cephalopods (e.g., octopus) and insects. While all start as single cells, different embryos develop to form very different organisms. The endless beauty and wonder of animals around us, like tardigrades on lichens, ctenophores in sea water, and butterflies on flowers, is intriguing and inspiring. It is even more intriguing and inspiring how some of the developmental concepts and mechanisms could apply not only to animals, but also plants and microorganisms.

In addition to the diversity in organisms that were available to study embryonic development, I had the privilege to interact and do science with a very diverse group of people, coming from different research backgrounds. I learned a lot about regeneration from Jack Allen and Anneke Kakebeen who work on regeneration in planaria and frogs, respectively. Aastha Garde and Sandra Edwards provided insights on cell migration, cell invasion, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. This jived very well with Jayson Smith’s expertise on the cell cycle. On another hand, Katherine Nesbit emphasized the interplay between development of embryos and their environment. Meanwhile, Stefania Gutierrez gave fresh perspectives on animal development with her expertise in colonial tunicates. In parallel, Laurel Yohe and Melvin Bonilla offered a distinct evolutionary point-of-view on acquisition of traits. Andrew Fraser and Shinuo Weng, our mechanical engineers, uniquely saw embryogenesis in terms of forces and mechanics, and Bruno Moretti, our physicist, lended his expertise in optics for functional imaging of developmental processes. Anna Yoney was the go-to person on germ layer patterning, while Darcy Mishkind was the in-house expert on left-right asymmetry. We also had people in the batch who worked on development of reptiles, with Ashley Rasys studying eye development in lizards and Boris Tezak investigating sex determination in turtles. Maximilien Courgeon was most keen on studying the development of the brain and the nervous system. Martyna Lukoseviciute and Marla Tharp were the specialists on gene regulation and chromatin dynamics, while Weiyi (Lily) Tang and Andrea Attardi were the experts on gene regulatory networks. Catherine May was particularly interested in the evolution of cell types, and Shiri Kult was most curious about bone and cartilage development.

While we all worked on the same group of organisms during the course, equipped with our expertise, we tackled the development of these animals at different vantage points. We became more aware of our skill sets, which complemented each other. Being in a diverse group allowed us to challenge dogma, encouraged us to be comfortable with our ignorance, and let us acknowledge the gaps in our knowledge. This created an environment where we embraced naivety, which proved to be conducive in being bold and asking fearless questions. We found ourselves doing classical experiments that were performed by Hilde Mangold and Hans Spemann on frog embryos, Thomas Hunt Morgan on planaria, and Ethel Browne on hydra. We explored the promise of modern approaches in developmental biology research, like advanced and quantitative imaging, 3D printing, and CRISPR-Cas. We took on risky projects, embraced failure (which happened quite often), and celebrated success (when it happened very seldomly). Together with the faculty and the TAs, we relied on each other to supplement our understanding of embryology. Together, we learned beautiful and wonderful things.

ON THE BEAUTY AND WONDER OF DIVERSE RESEARCH BACKGROUNDS

Outdoor Sweat Box (question and answer session) with Susan Strome.

Photo credit: David Sherwood

The enthusiasm, joy, and excitement transcended gender identity and sexual orientation, nationality, and cultural background. This camaraderie went beyond the lab, evident in our Sunday out-of-the-lab trips and spontaneous dance parties, our convergent extension-inspired presentation during the July 4th parade (please see B. Duygu Özpolat’s video here), and our victory during this year’s softball game with the Physiology course. The diversity catalyzed the building of a strong network of scientists and lifelong friends.

The Embryology course also showcased exemplary initiatives to promote inclusive and equitable access to developmental biology research. The microscopes we used, for example, were kindly sponsored by different companies like Zeiss, Nikon, Bruker, and Mizar. During a visit, Manu Prakash, together with Team Foldscope (check out their website here), distributed cheap paper microscopes and highlighted the importance of frugal science. Alexis Camacho-Avila, a very brilliant undergrad from an underrepresented minority group, attended the first two weeks of the course through the Society of Developmental Biology (SDB) Choose Development! Fellowship Program. Moreover, there were generous scholarship grants and fellowships available to cover the expenses of attending the course. Personally, I am grateful for the financial support from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Horace W. Stunkard Scholarship Fund, and The Company of Biologists. These initiatives, among others, ensure barriers to diversity in developmental biology research are overcome. Witnessing and experiencing this was empowering.

ON THE BEAUTY AND WONDER OF DIVERSE DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGISTS

Embryology Course 2018 class photo, taken at the Waterfront Park in Woods Hole.

Photo credit: Bruno Moretti

Like the embryos we study, the community of developmental biologists has evolved to take endless forms. We are biologists, chemists, and physicists. We dance, ride a skateboard, and win softball games. We are parents, sons, and daughters. We come from different parts of the world, speak different languages, and grow from different cultural backgrounds. While being different, we share the passion to push developmental biology research forward.

Before ending, I would like to use this platform to thank various people who made the Embryology Course special. I thank my classmates whom I shared this truly transformative experience. I thank Christopher Pineda, Amber Rock, and Hannah Rosenblatt, our Course Assistants, who made sure the course ran smoothly. Also, I express many thanks to all the faculty and teaching assistants (TAs), who shared their knowledge and wisdom. I am further thankful to Richard Schneider and David Sherwood, our Course Directors, for granting me this life-changing opportunity. Lastly, I am grateful to my family, my lab, and every one who supported me and encouraged me to apply. I am very grateful to be part of #embryo2018 (a Twitter-friendly collective term referring to Embryology Course 2018 and every one who took part in it).

It has been around a month since I left Woods Hole. While I recollect on everything that happened during the Embryology Course and reflect on how it has a significant impact on what I do now and in the future, the weather here in Heidelberg has become cooler and the leaves on trees have started to turn into different shades of red. This summer is ending most beautifully and most wonderfully.

(18 votes)

(18 votes)