Preprints and science news – how can they co-exist? A meeting summary

Posted by mpalfy, on 25 February 2019

Mate Palfy & Gautam Dey

In the summer of 2018, two commentaries from the Science Media Center (an open letter from Chief Executive Fiona Fox and a ‘World View’ in Nature news by Senior Press Manager Tom Sheldon) voiced concerns about how preprints in the life sciences could pose a potential threat to science reporting in the mass media. These articles initiated (often heated) debates within the scientific community, underlining the need for public discussions between researchers, press officers and journalists. Open Research London, a London collective of academics and librarians, and the Open Access team at the Francis Crick Institute, led by Head Librarian Frank Norman, collaborated to nucleate a platform for such discussions through an evening event at the Crick on the 6th of February.

Jane Hughes, Director of Communications at the Crick and chair of the event, kicked off the evening by asking a large audience whether they think preprints need to change or, instead, whether science reporting must adapt – with an overwhelming show of hands for the latter option.

This set the stage for Tom Sheldon, who acknowledged that preprints have been tremendously useful for science, but warned about unforeseen side-effects – such as a potential dismantling of the press embargo system. He made a strong case for preserving embargoes: for accuracy, as they give journalists time to assess claims and solicit expert comment, and for impact, ensuring maximal reach for important findings. In the case of a controversial study claiming that genetically modified maize and Roundup can cause tumours and early death in rats (since retracted), he pointed out that embargo policies gave journalists the time to consult experts, who were quick to identify significant flaws in the study. As a result, many articles in the mass media (e.g. BBC and Reuters) reported the scepticism surrounding the research. Sheldon noted that if the criticism had followed the breaking news, it would have been too late, buried by the next news cycle. In a second example, a major clinical trial showed that e-cigarettes are more effective than nicotine replacement therapies in helping smokers to quit. In this case, the embargo helped these findings make it to the front page of multiple newspapers simultaneously, maximising impact.

Sheldon then went on to envisage how such stories concerning human health might have been covered had the study been posted as a preprint. In the first hypothetical, he argued a journalist might have rushed to cover a study without consulting experts, thereby misinforming the public. In the second hypothetical, initial reporting on the preprint might have made an embargo pointless or incompatible with journal policies- meaning the story would never make it to multiple news outlets, leaving the public uninformed about important results. Sheldon then concluded that preprints necessarily disrupt the current system and – even though there have so far been no examples of preprints causing damage – we must ensure that the public understanding of science is not a casualty. In his opinion, we cannot expect journalists to change, and it is publishers, scientists and press officers who carry the responsibility to adapt.

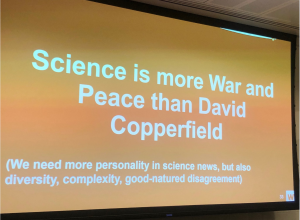

Clare Ryan, Head of Media Relations at the Wellcome Trust, shared Sheldon’s view that we won’t be able to change journalism, and should aspire to influence press officers, scientists and journals instead. In her talk, she suggested that the focus of science news should shift away from journal papers. After using a clip from John Oliver’s popular weekly show to showcase some major issues with science news, she went on to explain her vision of science in the media. Instead of forcing each ‘new discovery’ into the spotlight of the daily news (which doesn’t reflect the gradual, self-correcting nature of scientific progress in real life), journalists could aim to include more personality, complexity, and also disagreement in their stories. ‘Science is more War and Peace than David Copperfield’, after all, and we should seek to give the public better insights into how science really works. She ended with some practical advice, including ‘stop writing so many press releases!’, a sentiment that resonated strongly with the audience. Later in the Q&A session, Fiona Fox also emphasized that press officers should never write a press release about a preprint.

Robin Lovell-Badge, Senior Group Leader at the Francis Crick Institute, shifted the discussion towards the values of preprints in his talk titled ‘Preprints are the future’. After calling out some limitations of traditional journal publishing (such as cost, speed, and a peer-review process that doesn’t work too well), he also gave several examples of big studies published in the top journals, which later had to be retracted (e.g. the fraudulent Wakefield study on the link between MMR vaccines and autism), arguing that just because something is peer-reviewed does not mean it is sound. Quoting Michael Eisen, ‘the biggest threat to the proper public understanding of science is not preprints – it’s the lie we tell the public (and ourselves) that journal peer review works to separate valid and invalid science.’

Lovell-Badge then listed numerous well-known benefits of preprints, contrasting it with journal publication. For example, data and methods can be accessed much earlier when preprinted, and these are usually of high quality; he reasoned that since the work can be evaluated by the whole community, authors often take extra care to make sure what they post is valid. He suggested the rise of preprints gives us a good opportunity to create a new system that more rapidly, effectively and fairly engages the scientific community to assess the validity, audience and impact of published works. In such a system, it is also possible to review papers at any point, thereby contributing to an evolving understanding of the value and impact of the work. In contrast to the two speakers before him, he did think that journalists have a major responsibility in how science news is reported in the mass media.

The final speaker of the evening was Teresa Rayon, postdoctoral researcher at the Francis Crick Institute and member of the team of early-career researchers at preLights. She started her talk with a reminder that in our digital age, there are plenty of ways to communicate research transparently and get the society engaged with science (e.g. through blogging, social media). Recent data about the first five years of bioRxiv (also discussed here) highlights potential indicators (e.g. number of downloads) of preprint quality and impact, which could help journalists eager to report on preprints. She then introduced preLights, a community platform where early-career scientists highlight preprints they feel are important; taking the audience through her first preLights post as an example, she stressed the value of expert yet accessible opinion on a piece of work, and of open correspondence with preprint authors. Gratifyingly, the authors acknowledged the discussion prompted by her preLights post in the open peer review report associated with the final published paper. Rayon went on to illustrate the preLighter community’s commitment to preprints and open science by summarizing the important points from their commentary on why preprints promote transparency and communication, rather than distortion and confusion. Finally, she proposed that initiatives like preLights can help science reporting by highlighting work to scientists, journals and journalists (without the use of jargon), having a community of experts who can give their opinion (similar to the community of experts at the Science Media Centre), and giving a voice to the new generation of researchers, who are eager to improve communication with journalists.

The prolonged, animated, and ultimately inconclusive discussion that followed these presentations highlighted just how essential it is to initiate and encourage conversations that bring together journalists, press officers, scientists and activists. There appeared to be a reasonably broad consensus that, pending further changes in the science publishing landscape, it might be necessary to have a self-imposed moratorium on mainstream reporting on preprints, giving the work time to accrue established modes of peer-review and community approval before its wider dissemination.

Given the tight deadlines of science reporting and the pressures of the newsroom, in the longer term it will be incumbent on advocates of preprints and publishing reform to familiarise journalists and press officers with the broader ecosystem around preprints. Ultimately, we believe that open community curation and peer review can provide a treasure trove of information that will complement and enrich the traditional reporting model consisting largely of a stamp of approval provided by 2-3 peer reviewers and journal editors.

Curious about the discussion? Take a look at #ORLFeb19 on Twitter!

We thank Teresa Rayon and Frank Norman for feedback on the post

(12 votes)

(12 votes)