The Arterial Maze: Unveiling the Origin of Pial Collaterals in Mouse Brain

Posted by Swarnadip Ghosh, on 19 February 2025

Written by Swarnadip Ghosh & Soumyashree Das

Behind the Paper Story of “Development of pial collaterals by extension of pre-existing artery tips”

What we do and how we do it?

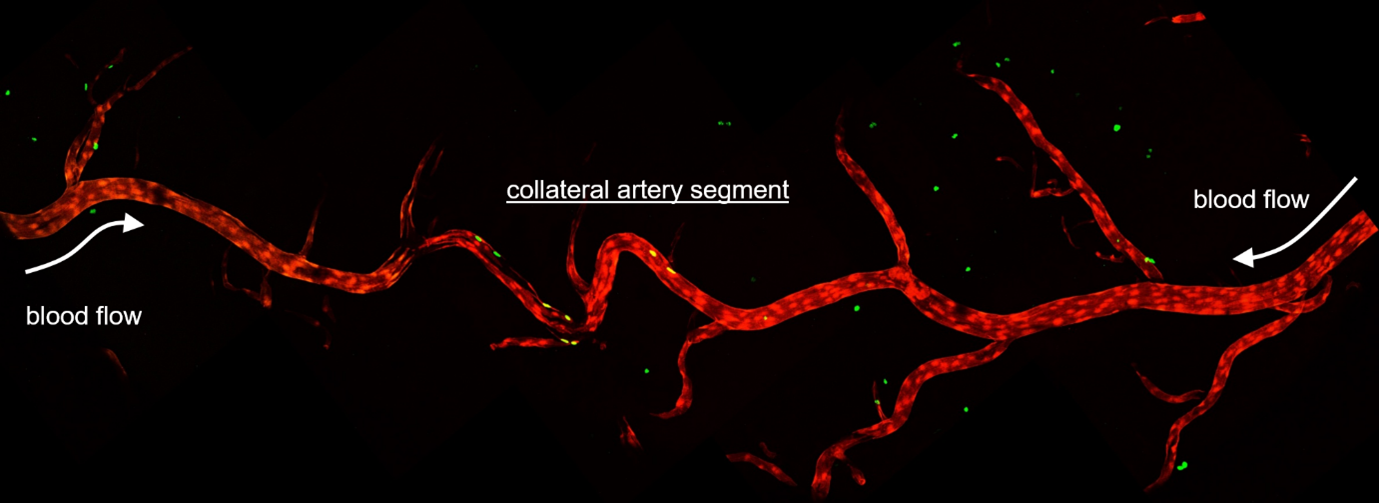

Arteries are an essential part of any tissue. For the tissue or organ to survive, it needs to be perfused with blood carrying nutrients and oxygen, which gets distributed through capillaries and keep cells alive and healthy. We use artery development as a model to ask questions about cellular responses, interactions, heterogeneity and plasticity. Specifically, we use a special kind of artery¾the collaterals (Figure 1), to ask important questions about biological processes.

Collateral arteries are special because these connect two arterial trees. So, if/when there is a clog in one of the artery branches, the collaterals reroute the blood flow and continue perfusing the underlying tissue without interruption. This ensures healthy and functional organs.

To date, we have not identified a molecular marker for collaterals, which, prevents us from distinguishing collaterals from conventional arteries on a tissue section or in the cellular clusters obtained via analyses of single cell sequencing data. The only identifying characteristic of collaterals is the fact that they connect two artery trees. So, we use imaging of whole organs (in our case, mouse hearts) to identify the coronary arteries and subsequently, the coronary collateral arteries which connect them together. Along with imaging whole hearts with cellular resolution, we heavily use mouse genetics and gene expression datasets to build hypotheses and test them both in silico and in vivo.

Like all scientific studies, this work went through a number of roadblocks which inspired our team to take up the challenges in a systematic manner and tackle them one at a time. It was not straight forward. In the process, we made some inspiring discoveries, developed some new tools and opened avenues for several questions in the field of vascular biology. Here is our story.

The inspiration: Same but Different

While it seems like the properties of cells which compose vessels within an organism are same, scientific evidence points to the contrary. We and others (Arolkar et al., 2023; McDonald et al., 2018) have time and again shown that, the building block of arteries─artery endothelial cells─can be quite different. Research groups around the world have used a variety of experimental models to highlight the differences in their origin, function, plasticity and regenerative abilities. The molecular heterogeneity of endothelial cells within a given vessel segment is getting more and more attention (Augustin and Koh, 2017; Trimm and Red-Horse, 2022).

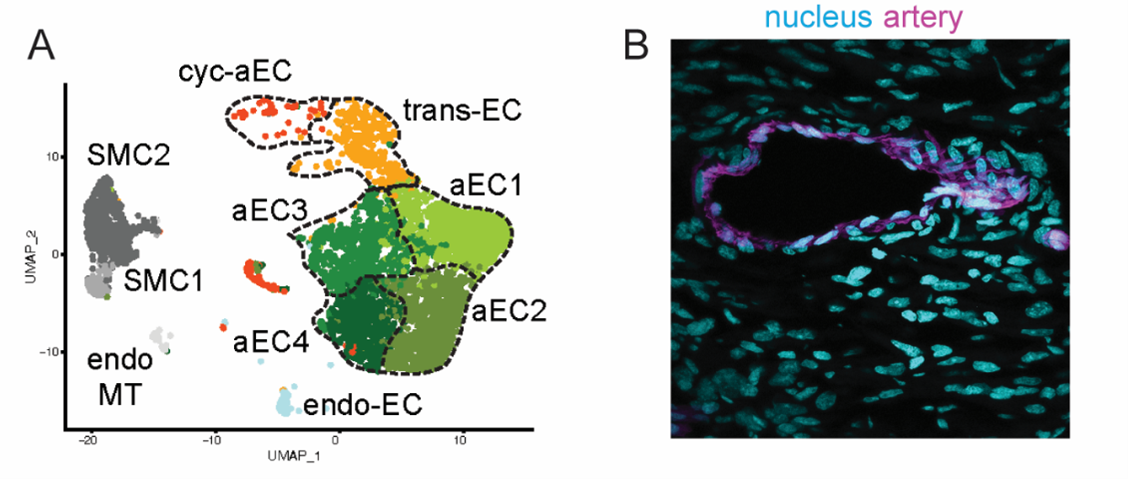

When we take a section of any vascularized tissue, and immunostain for arterial markers, like Cx40 or SMA, we cannot distinguish one cell from the other. We also know that these cells are different in their gene expression profiles (Arolkar et al., 2023). So, while the artery cells all look the same, they can be very different from each other (Figure 2). Cellular heterogeneity could be determined by their origin, which, consequently regulates the plasticity. This is a hypothesis, which we would like to test in as many ways as possible.

In our prior work we have done in silico and in vivo analyses of molecular properties of cardiac artery endothelial cells. In these studies, we have shown that only a small subset of artery cells is plastic enough to give rise to new cells, and that this plasticity is coupled to age¾the younger the hearts, the more plasticity (Arolkar et al., 2023; Das et al., 2019). That being said, we were always curious to test if this molecular heterogeneity within arteries is also observed in other organs.

The question and where to look

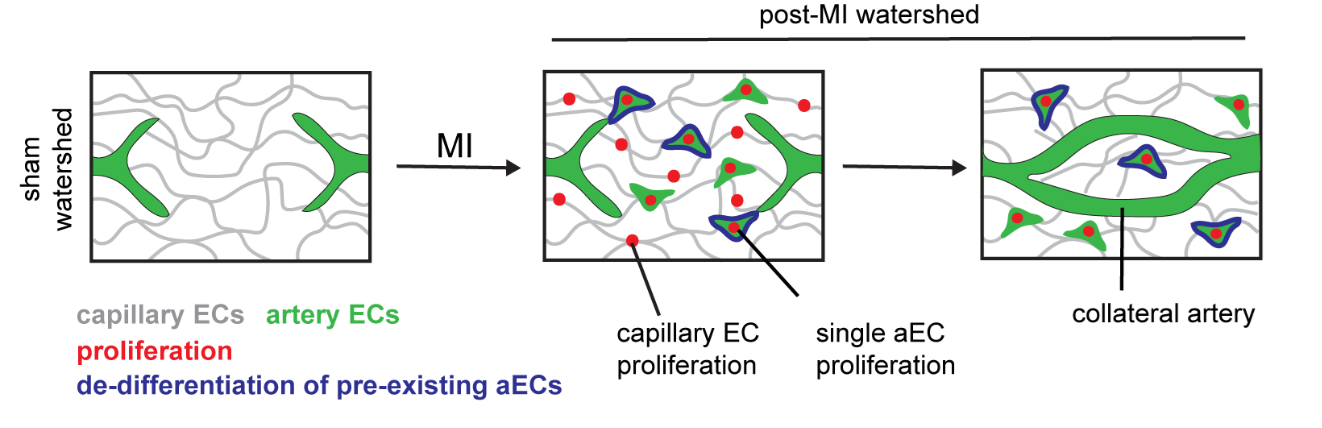

In mouse hearts, induction of myocardial infarction leads to dissociation of individual artery endothelial cells from pre-existing arteries. Only a subset of these dissociated single cells undergo proliferation, which results in massive expansion of this population. Eventually these cells come together and coalesce to build a collateral artery in the heart (Figure 3). We still do not understand what makes a small population (~8.4%) of artery endothelial cells more plastic than its neighbors. What is the relevance of such functional heterogeneity? Can these “plastic” cells, with proliferative properties, be distinguished molecularly from other artery cells? We continue to ask these questions in our lab.

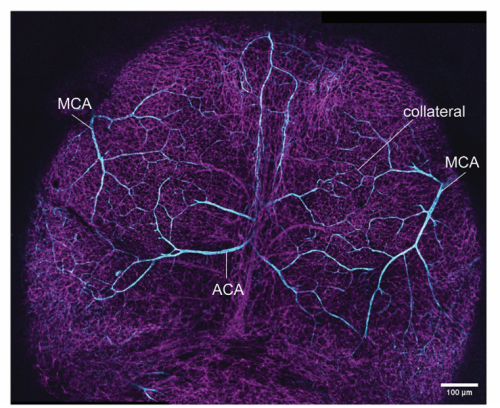

We are also curious about the occurrence of this unique biological process elsewhere in the mouse. So, we asked, if other critical (ischemia-prone) organs such as the brain, would demonstrate similar molecular heterogeneity within a given artery cell population. Luckily for us, apart from circle of Willis, which is embedded deep, the brain’s superficial layer, the pial layer, also has an extensive network of collaterals. This collateral network is formed between two major arterial trees, the middle cerebral artery and the anterior cerebral artery (Figure 4).

At the time, the brain was a new model to work on. The team did a thorough research on the anatomy and structure of mouse brain, especially how the arteries run through different segments of the brain, the time-lines, and the drivers. We read about different structures in the mouse brain and analyzed the gene expression patterns of various anatomic structures. We were surprised how little was known about the brain vasculature. Though stroke is one of the leading causes of deaths world-wide and have been known to us since ages, our approaches in its prevention or treatment is extremely limited (Bam et al., 2022; Grossman and Broderick, 2013). With all this in mind, we set off to ask our question: How do collateral arteries develop in a mouse brain? We chose to study pial collaterals to look for answers.

The hiccups: Mind the brain

While we were excited to start this new venture, we encountered the first bump very early on. A big challenge was to deduce a timeline. From earlier studies, we understood that pial collaterals in mouse brains were present at the time of birth, meaning, these structures developed during embryogenesis. We knew that tracking a developmental process could easily become very tricky. For starters, multiple overlapping cellular events during development could complicate our assessment of the timeline for the origin of pial arteries (middle and anterior cerebral arteries) and pial collateral arteries. Lack of a single molecular marker for collaterals would not let us distinguish arteries from collateral arteries.

The second challenge was more technical. The brain tissue was nothing like the heart¾it was squishy and lost its integrity post-processing. Preserving the integrity of the tissue and the embedded vasculature was a non-trivial task. We tried a variety of approaches, from isolating the pial layer (as a sheet) to sectioning and reconstructing different slices of brain tissue. But nothing worked.

The detours: Bypassing the blocks

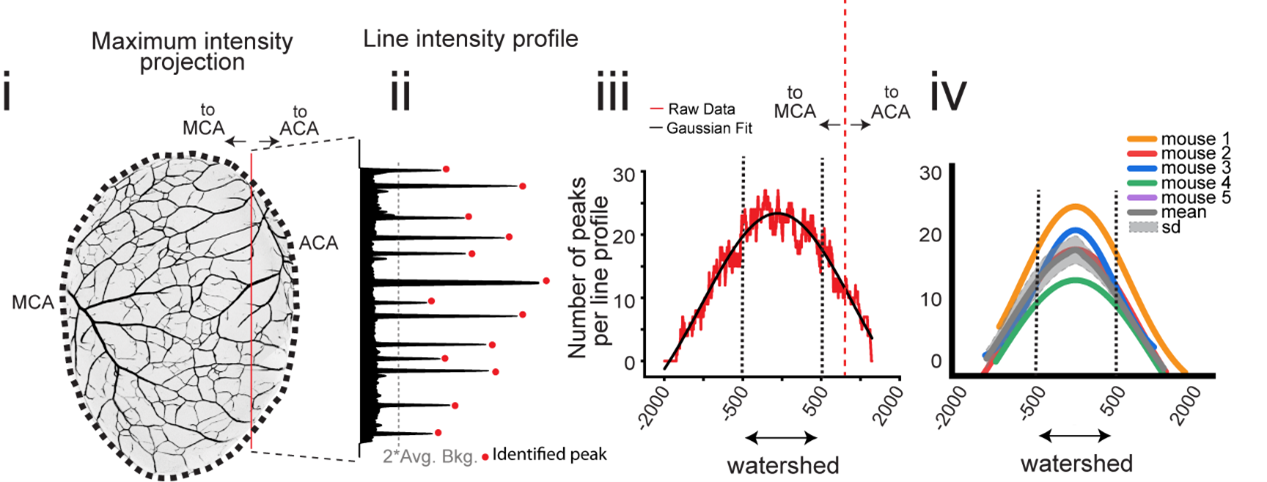

None of our (older) tactics allowed us to reliably visualize the collaterals. With time, we realized that we will need to develop new tools to address the questions we were asking. During the late-gestational period, when the pial collateral arteries develop (embryonic day (e) 15.5 to 18.5), the cranium and the skin (with its very own intricate vascular network) grow concurrently. This transformation posed a great obstacle for us to accurately visualize the pial blood vessels across different stages without the interference from surrounding tissue. It took us a year and a half to optimize a method for immunostaining and whole brain imaging of vasculature, with cellular resolution. After many trials and errors, we had a protocol which allowed us to confidently identify pial collaterals in all stages of developing mouse brain. Alongside, we also developed a quantitative method (Figure 5) to distinguish pial arteries from pial collaterals. Eventually, we were able to leverage this quantitative approach to delineate the precise timeline for development of pial arteries vis-à-vis collaterals in the mouse brain. With this, our curiosity deepened. We asked what was the cellular lineage of the pial collaterals. To address these questions, we utilized several transgenic mouse lines which enabled us for genetic fate mapping of the endothelial cells that form collateral arteries. As anticipated, we found a major cellular contribution (77%) from the preexisting artery cells with a smaller but notable contribution (31%) from the capillary cells, resulting in a mixed lineage composition.

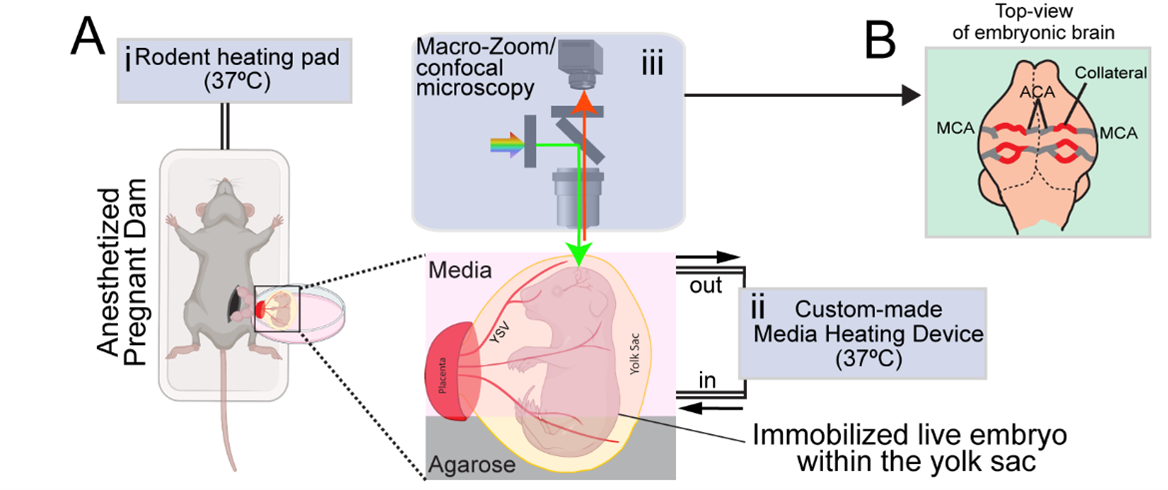

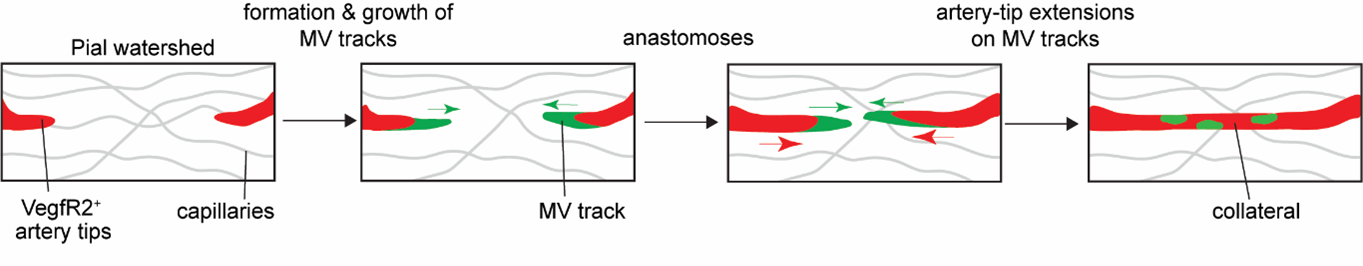

We next asked how pial collaterals form. This led us to embark on a new phase of investigation using in vivo experimentation and whole organ imaging to capture snapshot of the developmental process. Here we encountered one of the most formidable challenges. From immunostaining fixed samples, we realized that pial collaterals develop rapidly during embryogenesis. After a series of unsuccessful attempts to capture the cellular process in action, we refined our work-plan, and pushed the limits. We decided to build a system which allowed us to image brains of live embryos (Kawasoe et al., 2020; Yuryev et al., 2016). From immunostaining whole brains, we already knew that pial collaterals form in a very short time-range of 1-2 days. Hence, we hoped that keeping the embryo alive outside the mother’s womb for 3-4 hours (at the relevant gestational period, i.e., e16-e16.5) and making it accessible to microscopy, would help us capture the cellular dynamics involved in pial collateral artery development. We followed a surgical procedure where the developing embryos were taken out from the anesthetized pregnant dam. The embryos were still connected via umbilical cord and kept within the intact yolk sac. The whole set-up was kept adequately hydrated and temperature was stringently maintained to ensure the survival of the embryos. This set up was coupled with a (stereo and confocal) microscope to capture the vascular dynamics at cellular resolution (Figure 6). By live imaging embryos, we bypassed all biases and concerns, be it technical or biological. And the results were truly surprising and rewarding. The process we captured was distinct from what we observe in the heart. We captured pre-existing artery tips walking on defined microvascular structures (Kumar et al., 2024). It was exciting to observe the collaboration of artery and capillary endothelial cells.

We also systematically tested the role of CXCL12 and VEGF pathways in pial collateral development and remodeling. We chose these molecules as they are already known to perform critical functions during coronary collateral development, post-MI. Remarkably, in contrast to the heart, CXCL12 was dispensable for the development of pial collaterals during embryogenesis. While VEGF pathway was critical, it performed a very different function─helping in artery tip extension. We also performed longitudinal imaging of adult pial layer, and assessed the effects of hypoxia on individual artery cells which make up pial collaterals. Together, using a combination of mouse genetics and intravital/longitudinal imaging we showed organ-specific mechanisms drive collateral development in the brain and heart (compare Figure 3 with Figure 7).

This study was a result of combined output from a post-doctoral work, a part of doctoral research work and three master’s theses. It, indeed, was a team-driven pursuit and a notable example of curiosity-driven science. Many of the authors have moved on to their next stage of careers, continuing to explore multiple aspects of neuroscience and vascular biology. We anticipate amazing outcome from their works in near future.

References:

Arolkar, G., Kumar, S. K., Wang, H., Gonzalez, K. M., Kumar, S., Bishnoi, B., Rios Coronado, P. E., Woo, Y. J., Red-Horse, K. and Das, S. (2023). Dedifferentiation and Proliferation of Artery Endothelial Cells Drive Coronary Collateral Development in Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 43, 1455–1477.

Augustin, H. G. and Koh, G. Y. (2017). Organotypic vasculature: From descriptive heterogeneity to functional pathophysiology. Science (1979) 357,.

Bam, K., Olaiya, M. T., Cadilhac, D. A., Donnan, G. A., Murphy, L. and Kilkenny, M. F. (2022). Enhancing primary stroke prevention: a combination approach. Lancet Public Health 7, e721–e724.

Das, S., Goldstone, A. B., Wang, H., Farry, J., D’Amato, G., Paulsen, M. J., Eskandari, A., Hironaka, C. E., Phansalkar, R., Sharma, B., et al. (2019). A Unique Collateral Artery Development Program Promotes Neonatal Heart Regeneration. Cell 176, 1128-1142.e18.

Grossman, A. W. and Broderick, J. P. (2013). Advances and challenges in treatment and prevention of ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol 74, 363–372.

Kawasoe, R., Shinoda, T., Hattori, Y., Nakagawa, M., Pham, T. Q., Tanaka, Y., Sagou, K., Saito, K., Katsuki, S., Kotani, T., et al. (2020). Two-photon microscopic observation of cell-production dynamics in the developing mammalian neocortex in utero. Dev Growth Differ 62, 118–128.

Kumar, S., Ghosh, S., Shanavas, N., Sivaramakrishnan, V., Dwari, M. and Das, S. (2024). Development of pial collaterals by extension of pre-existing artery tips. Cell Rep 43, 114771.

McDonald, A. I., Shirali, A. S., Aragón, R., Ma, F., Hernandez, G., Vaughn, D. A., Mack, J. J., Lim, T. Y., Sunshine, H., Zhao, P., et al. (2018). Endothelial Regeneration of Large Vessels Is a Biphasic Process Driven by Local Cells with Distinct Proliferative Capacities. Cell Stem Cell 23, 210-225.e6.

Trimm, E. and Red-Horse, K. (2022). Vascular endothelial cell development and diversity. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2022 1–14.

Yuryev, M., Pellegrino, C., Jokinen, V., Andriichuk, L., Khirug, S., Khiroug, L. and Riverat, C. (2016). In vivo calcium imaging of evoked calcium waves in the embryonic cortex. Front Cell Neurosci 9, 173603.

(1 votes)

(1 votes)