The human sex ratio at conception and the conception of scientific “facts”

Posted by steven orzack, on 9 June 2015

Few things interest many people more than sex. For some, this means interest in practices and partners. For others, it means producing a son. There is an ocean of claims about how to do this. A quick Google search reveals claims that a woman can up the odds of a son by taking cough syrup, avoiding intercourse in the days before ovulation, achieving female orgasm, increasing sodium and potassium intake, decreasing calcium and magnesium intake, avoiding exercise, avoiding the missionary position, and increasing caffeine intake by the father.

As a scientist, it’s easy to dismiss such claims as folklore. Yet, science is sometimes no less tangled up with claims that amount to folklore, but which are widely accepted as scientific fact. This entanglement is well-illustrated in another manifestation of fascination with sex: the study of the human sex ratio.

Investigations of the sex ratio (often calculated as the proportion of males) date back at least to Graunt (1662) who described an excess of male births (Campbell 2001). By the late 1800s it was clear that more males than females die during later pregnancy (Nichols 1907). By the 1920s, the claim that the sex ratio at conception or “primary” sex ratio (PSR) is more male-biased than the birth sex ratio was widespread (e.g., Parkes 1926). Just how startling this is can be understood by considering what people knew back then. Other than the excess of male births, what data were available that could allow inference of the pre-birth sex ratio? Only samples of spontaneous abortions (Tschuprow 1915); the resulting sex ratio estimates were often, but not always, male-biased. Sexing was based on morphology, which is likely to generate a male-bias, especially for young fetuses. What data were not available? There were no sex ratio data derived from samples of embryos and/or extant pregnancies; such samples are now available from assisted reproductive technology (ART) and from chorionic-villus sampling and amniocentesis (techniques to sample fetal cells). There were no biochemical or molecular methods to detect the sex of a fetus or to assess whether it was karyotypically normal. In addition, there were no statistical methods to properly account for the complexities of data sets involving proportions.

Despite the concerns raised by some as to the problematic nature of inferring the PSR from spontaneous abortion data (e.g., MacDowell and Lord 1925), the male-bias of the PSR became a scientific fact. One reason is that scientists abhor a vacuum. This is not inherently problematic. After all, scientists could do nothing if “complete” knowledge was a prerequisite for any analysis. What is problematic is that claims for the male-biased PSR were usually shorn of connection with underlying data. Consider, for example, Shettles’ (1961, p. 122) opening statement that “In every population, more males than females are born, and still more are conceived.” This “digestible” fact about the PSR is memorable because of its unqualified simplicity, which makes it highly transmissible, especially given its main constituency: medical doctors (readers of Obstetrics and Gynecology). (Shettles provided citations later in his paper that he regarded as supporting his claim. He does not discuss the data; none of the citations contain data that are necessarily consistent with a male-biased PSR and not all even contain a claim about the PSR.) “Drinking from a firehose” comes to mind as an apt descriptor of medical training, so much so that the acquisition of this kind of digestible fact is an essential cognitive “device” for the completion of training. In this context, this device supercharged the spread of the claim of a male-biased PSR shorn of connection with data.

The post-WWII standardization of medical training in part driven by the wide adoption of a few textbooks accelerated the spread of the digestible fact about the PSR. For example, Stern’s (1960) widely-used and high-quality textbook on human genetics presented the claim that the PSR is male-biased and even went so far as to describe some of the data; however, possible sampling biases associated with the data went unmentioned.

The spread was also facilitated because many types of scientists regarded the male-biased PSR as basic knowledge. Groups with an interest in the topic included cell biologists, developmental biologists, demographers, epidemiologists, evolutionary biologists, gynecologists, and statisticians. This “balkanization” provided a perfect opportunity for a fact to be accepted more on its perceived acceptance by others than on the data themselves. One can readily imagine that, say, demographers pressed about the empirical basis for the male-biased PSR would state something along the lines of, say, “the gynecologists figured that out”. In part, the knowledge dynamic is similar to the game of “telephone” in which partial information at best is (re)transmitted. Here, the scientific argument underlying the message got lost in the transmission. Ironically, this occurred even though multiple professions had a stake in the problem, which at first blush one imagines might have fostered independent investigations. Instead, the presence of multiple professions likely had the opposite effect.

Sex ratio data derived from spontaneous abortions could provide a meaningful estimate of the PSR. Why did this not happen? The degraded knowledge dynamic described above limited any serious engagement with the complexities of how to use such data to estimate the PSR. For example, many fetuses die without the mother knowing she is pregnant and so are not included in samples of spontaneous abortions. Backwards extrapolation of the early sex ratio from later sex ratio data is possible but must be done very carefully. In addition, spontaneous abortions were usually regarded as unbiased samples from a population of fetuses having a male-biased PSR. The alternative possibility that the estimates arose from biased samples of a population having an unbiased PSR received little attention, and so possible corrections for a sampling bias went undeveloped.

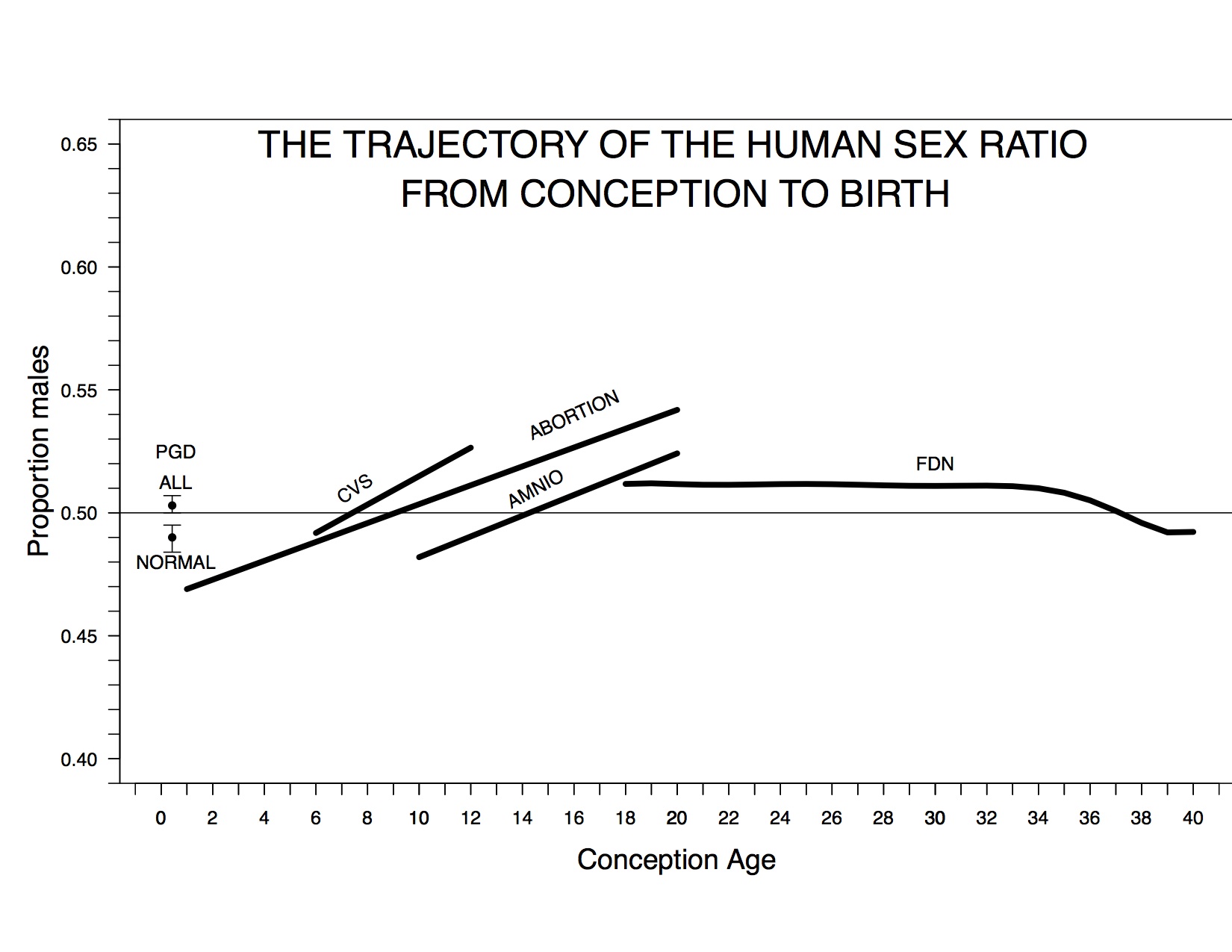

My colleagues and I recently estimated the trajectory of the sex ratio from conception to birth by analyzing three-to-six-day-old embryos derived from ART procedures, fetuses from induced abortions, fetuses that have undergone chorionic-villus sampling or amniocentesis, and US census records of fetal deaths and live births (Orzack et al. 2015).

The trajectory of the cohort sex ratio from conception to birth. “PGD All” and “PGD Normal” denote the total and normal sex ratio estimates based on ART embryos, CVS denotes the estimated sex ratio trend based on chorionic-villus sampling data, ABORTION denotes the estimated trend based on induced abortions, AMNIO denotes the estimated trend based on amniocentesis data, and FDN denotes the trend of cohort sex ratio based on US fetal deaths and live births. A dashed line denotes a sex ratio of 0.5.

Our assemblage of data is the most comprehensive ever assembled to estimate the PSR and the sex ratio trajectory and is the first to include all of these types of data. We found that the sex ratio at conception is unbiased, the proportion of males increases during the first trimester, and total female mortality during pregnancy exceeds total male mortality (contrary to long-held opinion); these are fundamental insights into early human development (Austad 2015).

Our analyses avoided the perils of backward extrapolation (because we have data from embryos that are just a few days old) and the potential bias of estimates based on spontaneous abortions (because we did not use such data). On the other hand, our estimate of the PSR is potentially biased because most, but not all, ART embryos are conceived outside of mothers. Our estimate of the trajectory of the sex ratio after conception might also be biased because it is based in part on sex ratio data from mothers undergoing diagnostic procedures. As described in our paper, we believe that these potential biases do not influence our estimate of the PSR and of the trajectory. Nonetheless, we encourage scrutiny of potential biases influencing our analyses. Whatever the outcome of such scrutiny, our analyses set a new standard for analyses of the pre-birth human sex ratio, one that we hope will end the degraded knowledge dynamic that has long held sway in the study of the pre-birth human sex ratio.

References:

Austad, S. (2015). The human prenatal sex ratio: A major surprise Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 (16), 4839-4840 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1505165112

Campbell, R. (2001). John Graunt, John Arbuthnott, and the Human Sex Ratio Human Biology, 73 (4), 605-610 DOI: 10.1353/hub.2001.0048

Graunt, J. 1662. Natural and Political Observations Made Upon the Bills of Mortality. London: Martyn.

MacDowell, E. C., and E. M. Lord. 1925. Data on the Primary Sex Ratio in the Mouse. Anatomical Record 31: 143–148.

Nichols, J. B. 1907. The Numerical Proportions of the Sexes at Birth. Memoirs of the American. Anthropological Association 1 (4): 247–300.

Orzack, S., Stubblefield, J., Akmaev, V., Colls, P., Munné, S., Scholl, T., Steinsaltz, D., & Zuckerman, J. (2015). The human sex ratio from conception to birth Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 (16) DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1416546112

Parkes, A. (1926). The Mammalian Sex-Ratio Biological Reviews, 2 (1), 1-51 DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1926.tb00600.x

Shettles, L. B. 1961. Conception and Birth Sex Ratios. Obstetrics and Gynecology 18 (1): 122–130.

Stern, C. 1960. Principles of Human Genetics. 2nd ed. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Tschuprow, A A. 1915. Zur Frage Des Sinkenden Knabenüberschusses Unter Den Ehelich Geborenen. Bulletin de L’institut International de Statistique 20 (2): 378–492.

(1 votes)

(1 votes)