Fish, Frogs, Friends, Lend me your Ears.

Posted by Mathi Thiruppathy, on 6 March 2025

Humans and other tetrapods evolved from aquatic fish. In making this leap, tetrapods evolved lungs to breathe air and lost respiratory gills. It is tempting to intuit that lungs evolved from gills. However, lungs and gills form in separate parts of the body, so they are unlikely to be evolutionarily related. Indeed, some living fish have both gills and lungs [1]. So, what became of fish gills? In work spanning the last 6 years and published in Nature, we show that gills may in fact have contributed to the origin of a functionally unrelated structure in humans – our outer ears.

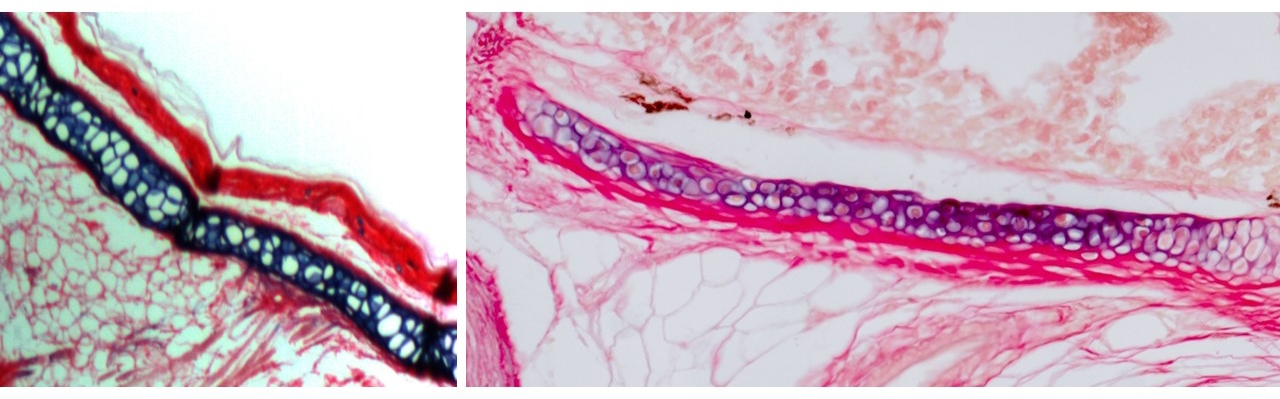

The outer ear, comprising the ear canal and flap-like pinna, is a unique feature of mammals with no known evolutionary precedent in reptiles or amphibians. At first, our research centered on the elastic cartilage that supports it, previously described only in mammals [2-5]. Elastic cartilage has cellular and mechanical properties distinct from the more widespread hyaline cartilage in the adult nose, joints, and embryonic skeleton. But we knew almost nothing about molecular drivers of these differences. In previous work in the Crump lab I had helped describe a zebrafish gill cartilage with gene expression distinct from hyaline cartilage. Ensuing discussions with Max Plikus at UC Irvine and a wonderful collaboration with Andrew Gillis at the MBL (in which he single-handedly sectioned and stained gills from multiple fish species!), helped established that cartilage in the gills of bony fishes, including zebrafish, is elastic in nature.

I next asked whether the elastic cartilage in fish gills and the mammalian outer ear might represent a homologous cell type. With help from the Evseenko lab at USC and cross-country shipments from collaborators in the Chen lab at Mount Sinai (once during a hurricane!), I acquired single-cell gene expression and open chromatin profiles from elastic cartilage of the human fetal outer ear and epiglottis, as well as hyaline cartilage from the human nose as a control and compared these with our zebrafish data. These analyses confirmed significant gene expression similarities between fish and human elastic cartilage.

At this point, two major conceptual ideas significantly expanded the focus of this work.

First, the activity of non-coding genomic elements called enhancers tends to be more tissue-specific than expression of associated genes, thus serving as better proxies for regulatory conservation between cell types. The problem is that unlike genes, only a tiny proportion of human enhancers have sequence-conserved counterparts in the zebrafish genome. However, previous work had shown that regulatory information encoded in enhancers can be recognized by similar sets of factors across species [6, 7]. This gave me the idea to sidestep the issue of DNA sequence conservation: if elastic cartilage is specified by a conserved regulatory program, then human elastic cartilage enhancers encoding this program might still be recognized specifically in fish gills.

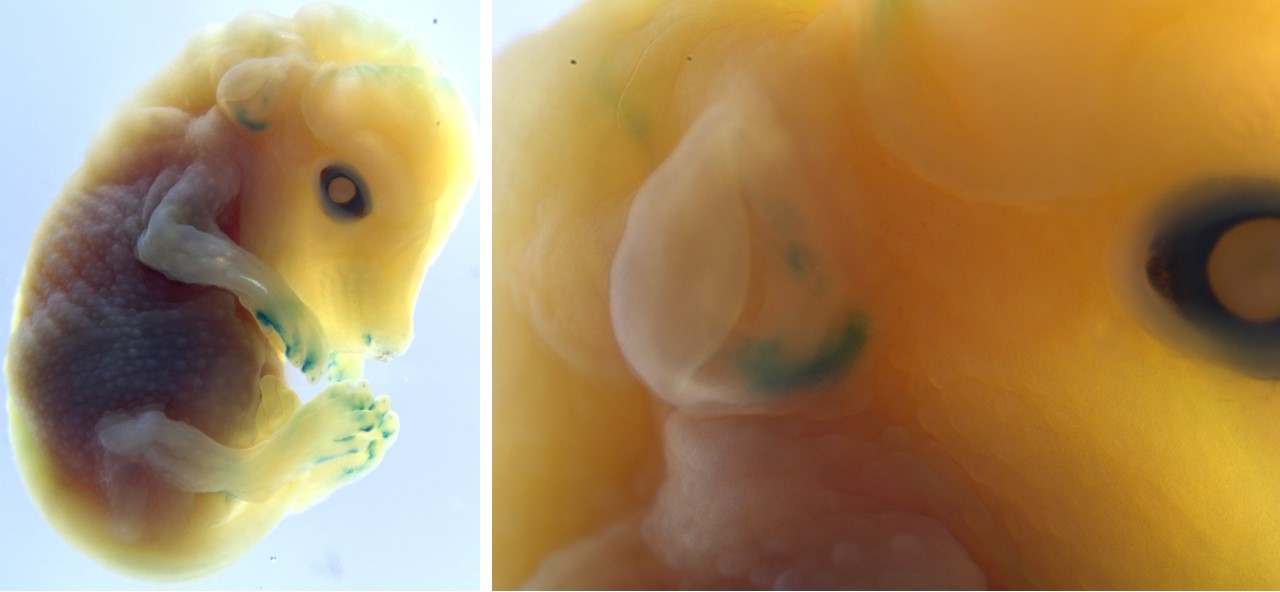

I identified human genomic regions representing putative elastic cartilage-specific enhancers and, despite absence of similar fish sequences, tested their activity in zebrafish. It was the most incredible moment of my PhD when I looked through the microscope to see six of ten human outer ear elastic cartilage enhancers driving fluorescent activity specifically in the gills, reflecting shared biology across 400 million years of evolution. Equally amazing, a zebrafish gill elastic cartilage enhancer drove highly specific activity in the elastic cartilage of the mouse outer ear.

Second, I was influenced by work in other model systems showing that seemingly novel structures can represent re-emergence of an ancestral structure that apparently disappeared during evolution but was in fact retained in a cryptic form in intervening species [8]. Could a broader gill developmental circuitry have been retained in tetrapods and repurposed in mammals to drive outer ear evolution?

I realized we could use a similar enhancer-based approach, but with a focus on developmental timepoints when gills first grow out. This led to the discovery that one of the few enhancers well-conserved between zebrafish and humans is active in gill developmental populations, but critically not in the later-forming elastic cartilage. It thus represents a piece of the ancient instructions to make fish gills retained in our own DNA. In transgenic mice, the zebrafish version of this enhancer was faintly but consistently active in the developing outer ear. These findings demonstrated that it is not simply the elastic cartilage but also the early developmental outgrowth program that is evolutionarily conserved between fish gill filaments and the mammalian outer ear.

So, what was this program doing in amphibians and reptiles? In the case of our middle ear bones, fossil data have revealed their progressive evolution from fish jawbones through amphibian and reptile intermediates [9]. By contrast, cartilage does not preserve well, so the current fossil record provides little information on how gills may have transformed into outer ears.

For answers, we again turned to enhancers. We formed a new, eleventh-hour collaboration with Helen Willsey at UCSF to test our enhancers in an amphibian – the frog. Helen and her postdoc Micaela gave me a crash course on staging, imaging, and staining Xenopus tadpoles in the final weeks of my PhD, patiently repeating injections to replace samples that I lost. The results were worth it: gill/outer ear outgrowth enhancers were active in developing tadpole gills, suggesting continuity in the developmental program from fish to tetrapods. Further, mature tadpole gills contained a little-characterized cartilage that activated both human and zebrafish elastic cartilage enhancers! Although transgenic testing was not feasible in reptiles, I collaborated with Tom Lozito at USC to examine histology of the ear in green anole lizards and found that the evolutionarily mysterious extracolumella is made of a permanent, elastic cartilage. These pieces of evidence helped put together a model through which fish gill developmental and cell type programs could have been repeatedly redeployed through the evolution of tetrapods.

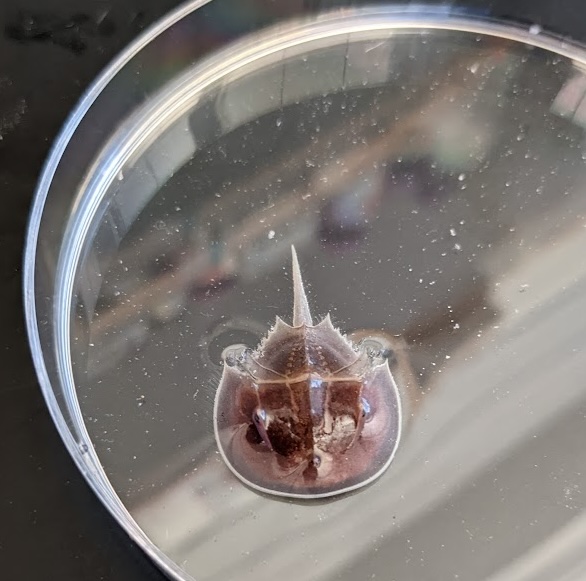

Finally, older reports had suggested that the horseshoe crab, an ancient invertebrate, makes a cellular type of cartilage-like tissue in its gills [10-13]. An exciting opportunity arose when I attended the wonderful Embryology Course held at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), which happens to be in Atlantic horseshoe crab territory. From chats I had there with invertebrate evo-devo aficionado Heather Bruce (now at the University of British Columbia), I got in touch with the Marine Resource Center, acquired a horseshoe crab specimen, and performed single-nuclei multiomic analysis on its unique “book gills”. Amazingly, a horseshoe crab gill enhancer drove transgenic activity in the zebrafish gills! Although we can do only limited experimental work in horseshoe crabs, our data suggest that gills and their elastic cartilage support may have an ancient origin in early bilateria.

Traditionally, fish gills were thought to have played little role in the evolution of tetrapods. Now, our work reveals an unprecedent legacy for this complex ancestral structure. Our research supports the idea of “deep” or “cryptic” homology: the morphological disappearance of a structure does not imply the disappearance of the developmental field from which it emerged or the regulatory program that instructed its formation. These developmental fields and regulatory programs can instead be reused to make something new, contributing to the widespread innovation we observe in nature.

1. Cupello, C., et al., Allometric growth in the extant coelacanth lung during ontogenetic development. Nature communications, 2015. 6(1): p. 8222.

2. Sanzone, C.F. and E.J. Reith, The development of the elastic cartilage of the mouse pinna. American Journal of Anatomy, 1976. 146(1): p. 31-71.

3. Bradamante, Z., B. Levak-Svajger, and A. Svajger, Differentiation of the secondary elastic cartilage in the external ear of the rat. The International journal of developmental biology, 1991. 35(3): p. 311-320.

4. Cox, R. and M. Peacock, The fine structure of developing elastic cartilage. Journal of anatomy, 1977. 123(Pt 2): p. 283.

5. Kostović-Knežević, L., Ž. Bradamante, and A. Švajger, Ultrastructure of elastic cartilage in the rat external ear. Cell and Tissue Research, 1981. 218: p. 149-160.

6. Wong, E.S., et al., Deep conservation of the enhancer regulatory code in animals. Science, 2020. 370(6517): p. eaax8137.

7. Minnoye, L., et al., Cross-species analysis of enhancer logic using deep learning. Genome research, 2020. 30(12): p. 1815-1834.

8. Bruce, H.S. and N.H. Patel, The Daphnia carapace and other novel structures evolved via the cryptic persistence of serial homologs. Current Biology, 2022. 32(17): p. 3792-3799. e3.

9. Gould, S.J., An earful of jaw. Natural History, 1990. 99(3): p. 12-18.

10. Person, P. and D.E. Philpott, The biology of cartilage. I. Invertebrate cartilages: Limulus gill cartilage. Journal of Morphology, 1969. 128(1): p. 67-93.

11. Person, P. and D.E. Philpott, Invertebrate cartilages. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1963. 109(1): p. 113-126.

12. Cole, A.G. and B.K. Hall, The nature and significance of invertebrate cartilages revisited: distribution and histology of cartilage and cartilage-like tissues within the Metazoa. Zoology, 2004. 107(4): p. 261-273.

13. Tarazona, O.A., et al., The genetic program for cartilage development has deep homology within Bilateria. Nature, 2016. 533(7601): p. 86-89.

(4 votes)

(4 votes)