The health impacts of microplastics are studied using a Xenopus amphibian model.

Posted by Jacques Robert, on 12 January 2026

Jacques Robert1,2 and Rachel F. Lombardo2

1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 14642, USA

2Department of Environmental Medicine, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 14626, USA

Introduction

Plastic particles and fibers shed from plastic debris, termed microplastics (MP), have become ubiquitous environmental pollutants found everywhere globally throughout marine and freshwater ecosystems (reviewed in [1]). Improper disposal, accidental loss, and fragmentation of plastic materials have led to an increase in MPs, which range in size from as large as 5 mm to as small as 1 mm. These MPs which can also be airborne, pollute environments as varied as urban landscapes, remote terrestrial regions, aquatic ecosystems. One of the highest waterborne MP concentrations reported in the USA is where Rochester’s Genesee River meets Lake Ontario [2]. In the air, soil and water, these MPs are consumed by a wide variety of organisms from invertebrates including mollusks and crustaceans to vertebrates such as fish, amphibians and ultimately humans. In humans, MPs accumulate in breast milk as well as various organs and tissues including the brain , liver, and placenta [3, 4]. Recently, MPs present in human tissues have increased from 2016 to 2024, especially in the brain [5]. While there is increasing evidence suggesting that MPs pose serious threats to aquatic ecology and human health, many aspects of their potential biological activity remain unclear. Notably, little is known about the potential lasting impacts of exposure to MPs during early development on immunity.

The study of biological effects of MPs has revealed multiple challenges including the wide diversity of plastic types that may or may not induce similar effects and the need for reliable biological models. While it is estimated that there are over 5000 different types of plastics composed of different polymers (e.g., nylon, polyethylene terephthalate, etc.) and chemical additives (e.g., flame retardants, plasticizers, etc.), the large majority of biological studies of MPs have used manufactured sterile polyethylene or polystyrene spherical beads of uniformized size. Moreover, under the actions of UV, temperature and pH in the environment, plastics fragment into a myriad of sizes and shapes, while their physical properties (e.g., porosity, hydrophobicity) are further altered during this process of aging. Finally, plastic debris sinking in water is associated with the formation of biofilms composed of diverse microbial communities, which may include pathogens [6].

To help fill these current gaps in knowledge surrounding MPs, we leveraged the amphibian Xenopus laevis as a robust comparative model. The X. laevis Research Resource for Immunology at the University is specialized in the development and use of Xenopus for immunological research. Fully aquatic tadpoles are ideal experimental organisms for addressing the acute and persistent biological impacts resulting from exposure to MPs, because their post-embryonic development, including the immune system differentiation is external and not protected by the maternal environment, which increases their sensitivity to perturbations by water pollutants. Furthermore, the development and physiology, as well as the immune system of Xenopus, are remarkably similar to that of humans which has led to fundamental discoveries about pathophysiology, development, and medical immunology [7-9].

Lake Ontario MicroPlastics Center

The research program using Xenopus is integrated into the Lake Ontario MicroPlastics Center (LOMP). This is a new collaborative initiative between the University of Rochester (UR) and the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). LOMP is a hub for research, translation, and community engagement, interested in investigating how different types of real-life plastics enter and move through the Great Lakes ecosystems and how MPs may affect human health under different environmental conditions. LOMP is one of six Centers for Oceans and Human Health jointly funded by the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. As mentioned above, besides marine ecosystems, significant quantities of MPs have been detected in Upstate New York lakes, rivers, and the drinking water of cities such as Rochester, NY [10]. This has led to the establishment of this productive collaborative research program between UR and RIT. An important component of LOMP is its Materials and Metrology Core that develops standardized protocols and produces optimized materials for the different research teams. For example, the Core provides silicon nanomembranes used for water and air filtration to quantify environmental MPs; it also prepares by cryomilling lab-made MP stock solutions in defined size ranges to mimic real-life MPs (Fig. 1A-C).

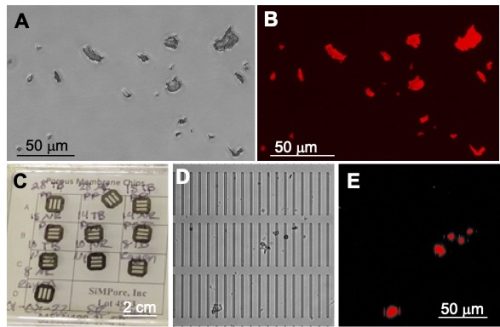

Figure 1: Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) MPs. (A) Bright field image and (B) RFP image obtained with an epifluorescence microscope of real-life PET-MPs of variable shapes and sizes (1-20 μm) stained with fluorescent Nile red dye. (C) Photograph of silicone nanomembranes (SimPore, Inc.). (D) Bright field image, and (E) RFP image of PET-MPs isolated on a nanomembrane (2 μm × 50 μm microslits) from liver lysates of tadpoles exposed for 7 days.

Biodistribution and biological impact of MP exposure in water on Xenopus

As part of the LOMP program, the objectives of the Xenopus research project are to determine the biodistribution and biological impacts of MP water contaminants using a sensitive and reliable experimental platform in X. laevis. The overarching hypothesis is that the developmental exposure to MPs will induce composition and size dependent long-term perturbations of immune homeostasis, chronic inflammation, decreased resistance to microbial pathogens and poorer antimicrobial immunity.

Using X. laevis tadpoles, we are conducting a rigorous assessment of the biodistribution and biological effects of MP ingestion, and specifically their potential to affect immune homeostasis and weaken the immune response to viral pathogens. In contrast to studies often using unrealistically large amounts of spherical microspheres (greater than 1 g/L), we are using smaller amounts of MPs (from 25 to 0.1 mg/L) that are closer to what is found in the environment. As a point of comparison, it is estimated that mineral water bottle can contain up to 0.6 mg/L of MPs [11], while European drinking water has been reported to contain 4,889 MPs per liter, which would correspond to about 2.6 mg/L [12]. We are focusing on two types of environmentally relevant plastics: polyethylene terephthalate (PET), which is extensively used in the packaging industry, and is a significant contributor to environmental plastic pollution [13] but is under-investigated [14]; and nylon 66 (nylon), which despite being one of the most abundant MPs in the microenvironments and detected in high amount in human tissues [5], there is little research about its biological impact. In collaboration with the other LOMP research teams, we also plan to test MPs isolated from Lake Ontario.

We first defined in detail the biodistribution, accumulation, and persistence of PET-MPs cryomilled to different size ranges: 1–100 μm [15] and 1-20 μm. These MPs were fluorescently labelled with Nile red for their detection by fluorescence microscopy on whole mount tissues and isolated peritoneal macrophages. The biodistribution was also evaluated by enzymatic digestion and silicon nanomembrane filtration (Fig. 1D and E). Even at concentrations as low as 0.1 mg/L, there was a rapid intestinal transit of PET-MPs leading to their accumulation as early as 24 hrs. of exposure in tadpole intestines, liver, kidneys, brain, and peritoneal macrophages, where they persisted for over a week after the initial exposure. We were able to estimate that a 2–3-week-old tadpole weighing approximatively 300 grams could ingest up to 2 mg of PET-MPs during the 24-hr. exposure. When transferring exposed tadpoles into clean MP-free water, a total of 1.7 mg of the MPs were released within 7 days. Thus, we estimated that on average 0.3 grams of MPs were retained in tadpoles one week after exposure, which correspond to 0.5-1 mg of MPs per gram of tadpole tissue.

To determine whether exposure to PET-MP has any effect on tadpole immunity, we took advantage of the ranavirus FV3, a major amphibian pathogen, which is a large double-stranded DNA virus. We have extensively characterized the pathogenesis and immune response against FV3 in X. laevis (reviewed in [16]). Notably, exposure to PET-MPs at a concentration of 10 mg/L for 1 month significantly increased tadpoles susceptibility to viral infection and altered innate antiviral immunity without inducing overt inflammation [15]. Further analysis of gene expression by qPCR revealed an altered expression of several genes critical for macrophage function (e.g., IL-34, MHC-II), which suggest that exposure to PET-MPs induces some macrophage dysfunction. Regarding the effect on development, we also noted that 1 month of exposure to PET-MP significantly delayed metamorphosis completion.

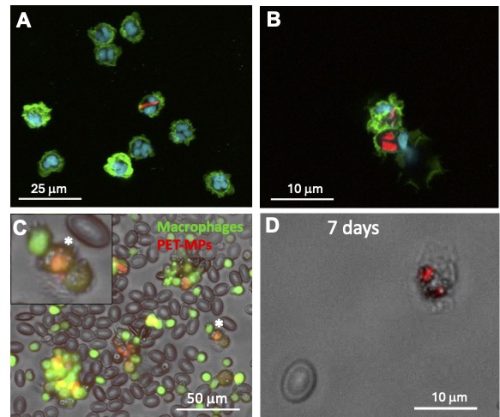

We are now focusing our investigation on the effects of MPs on macrophage function using both in vitro and in vivoapproaches. Interestingly, our preliminary results indicate that, compared to polystyrene or polyethylene manufactured spherical beads that are phagocytosed by a majority (>90%) of peritoneal macrophages from adult frogs at the same concentration, PET, and nylon 1-20 μm MPs fragments are internalized by only a minor fraction (~10%) of peritoneal macrophages. In addition, fewer PET and nylon MPs are internalized by individual peritoneal macrophage compared to manufactured spherical beads (Fig. 2A and B). We are in the process of developing a controlled aging process by UV treatment to determine if aged MPs might be phagocyted at a different rate than pristine MPs. To assess MP effect on macrophage function in vivo, we are taking advantage of the X. laevis transgenic line mpeg::GFP, where macrophages express the fluorescent GFP reporter. Intraperitoneal injection of a small amount of Nile red-stained PET-MPs in adult frogs allows the detection of GFP+ macrophages that have engulfed red fluorescent PET-MPs (Fig. 2C). Similarly, tadpole peritoneal macrophages can phagocytose red fluorescent PET-MPs following intraperitoneal injection. Moreover, we can detect macrophages with internalized PET-MPs up to 7 days after exposure (Fig. 2D), which suggests that, as also observed in vitro, MP engulfment does not induce marked cell death. This in vivo system will now allow us to follow the fate of macrophages with internalized MPs and determine whether their function in homeostasis, regeneration and immune response is altered.

Figure 2. In vitro and in vivo MP internalization assay. (A) Confocal microscopy images of adult X. laevis peritoneal macrophages (Mø) incubated with 10 μg/mL of Nile red fluorescently stained PET-MPs (1-20 μm) for 24 hours in vitro. (B) Similar peritoneal macrophages incubated with 10 μg/mL of Nile red fluorescently stained nylon-MPs (1-20 μm) for 24 hours in vitro. (C) Three days following the elicitation of Mø in the peritoneum, mpeg::gfp transgenic frogs with green fluorescent Mø were intraperitoneally injected with 10 μg of Nile red fluorescently stained PET-MPs. PLs were harvested 24 hrs. later by lavage and Mø with internalized MPs (orange) were visualized under a fluorescent microscope. (*) Magnification of a Mø with ingested PET-MPs. (D) Peritoneal macrophage from a tadpole (3 weeks of age) 7 days post-intraperitoneal injection with 10 μg Nile red fluorescently stained PET-MPs.

Regarding association of microorganisms with MPs, mycobacteria spp. were found in biofilms generated on plastic debris in a field mesocosm study in Lake Ontario and in the laboratory setting by our LOMP collaborators at RIT [6]. To further investigate the potential of MPs to interact with pathogens, we incubated PET-MPs with different mycobacteria species. M. marinum, a non-tuberculosis mycobacterium found in water around the world, can tightly bind to PET-MPs in vitro, as well as M. abscessus, which is a notable emerging human pathogen (Fig. 3). We plan to determine whether association of mycobacteria with MPs promotes their colonization in tadpoles and whether it affect infection and survival in macrophages.

Fig. 3: Tight association of non-tuberculous Mycobacterium abscessus with PET-MPs. M. abscessus expressing dsRED fluorescent reporter incubated overnight at 1×105 cfu in (A) 1 ml of amphibian PBS or (B, C) 10 µg of PET-MPs in 1 ml of amphibian PBS. The mixture was gently resuspended before examination under a fluorescent microscope.

In summary, our study using Xenopus carries substantial significance, raising developmental immunotoxicity (DIT) concerns not only for aquatic vertebrates but also for human health. The demonstrated impact on immune function underscores the broader ramifications of MP pollution, highlighting the need for comprehensive strategies to mitigate its pervasive DIT effects on both aquatic ecosystems and human populations.

Acknowledgements

The expert animal husbandry provided by Tina Martin is gratefully appreciated. We would like to thank Rachel F. Lombardo, Francisco De Jesus Andino and Hannah Turner for their significant experiment contribution as well as Drs. Lisa De Louise and Alison Elder for their critical review of this manuscript. The Lake Ontario MicroPlastics Center (LOMP) is jointly funded by NIEHS (P01 ES035526) and NSF (OCE-2418255). JR is also funded by NAID (R24-AI059830) and R.L. by the Toxicology Training Grant (T32-ES07026).

References

1. Frias, J. P. G. L. and R. Nash. “Microplastics: Finding a consensus on the definition.” Marine Pollution Bulletin 138 (2019): 145-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.11.022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X18307999.

6. Parthasarathy, A., A. C. Tyler, M. J. Hoffman, M. A. Savka and A. O. Hudson. “Is plastic pollution in aquatic and terrestrial environments a driver for the transmission of pathogens and the evolution of antibiotic resistance?” Environ Sci Technol 53 (2019): 1744-45. 10.1021/acs.est.8b07287.

7. LaBonne, C. and A. M. Zorn. “Modeling human development and disease in xenopus. Preface.” Dev Biol 408 (2015): 179. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.11.019. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012160615004716.

(2 votes)

(2 votes)