Behind the paper: “Spatially organized cellular communities shape functional tissue architecture in the pancreas”

Posted by Alejo Torres Cano, on 28 January 2026

How the project started

If you are in the pancreas field, you may be either part of the endocrine or the exocrine band. Now, this may not be like the Sharks and the Jets in West Side Story, but you better know your position. Whether this separation reflects the actual spatial segregation of both compartments and their different embryonic development is an idea perhaps worth exploring. In any case, our question was linked precisely to that spatial segregation: why do both compartments develop in different regions of the organ?

First of all, we know that what lies around the pancreatic epithelium (what we call the microenvironment) is crucial for its development. Since the 60s1, great works have progressively characterised the microenvironment with greater and greater detail, from early elegant experiments using explants, to more elaborate mouse genetics studies where specific cellular components and signalling pathways were perturbed2,3. The single-cell revolution brought a new twist: the degree of cellular heterogeneity populating the microenvironment, especially mesenchymal cells, was much higher than anticipated. The question then was: how is this heterogeneity spatially distributed?

Mapping the pancreas and deciphering maps.

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) appeared to us the best way to answer the question, but at the time we started the project, sequencing-based approaches did not provide the resolution needed to map a small, branched organ like the embryonic pancreas. On the other hand, image-based approaches only allowed for mapping the expression of a handful of markers. Thanks to the early discussions Francesca Spagnoli (PI of the lab) had with Cartana, the biotech at Karolinska Institute, which developed the In Situ Sequencing (ISS) technology and was later acquired by 10x Genomics, we were able to pioneer this approach. In parallel, access to the first single-cell RNASeq datasets of the murine embryonic pancreas -from our lab and others in the field4– enabled us to identify the most informative set of marker genes and design robust panels for the ISS experiments. Running the ISS technology on pancreas was not immediately immediately straightforward; it required considerable effort and a series of optimization experiments carried out by me and another postdoc in the lab., Jean Francois Darrigrand. Finally, by profiling the spatial distribution of sets of markers, we were able to create a cartography of the mouse embryonic pancreas (Fig. 1).

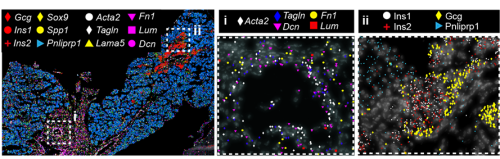

Fig. 1 ISS image of selected marker genes in E17.5 pancreas. Close-ups of selected probe genes and their spatial distribution in the tissue are shown in (i) and (ii) dashed boxes.

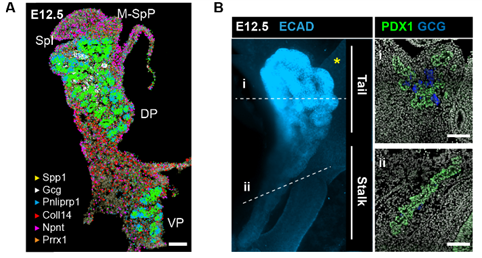

But a map is only an instrument, and the information obtained from it will largely depend on how you read it. When analysing a geographical map, your answers may vary depending on the level of aggregation: you can look at it from the country perspective, zoom in and separate by region or zoom in even more and analyse every city and small town independently. Similarly, when observing an organ, one can use different magnification lenses. First, the pancreas originates from two groups of progenitor cells growing independently (dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds), until they fuse around E14.5 in the mouse embryo. As shown in the 3D images below, generated by a PhD student in the lab, Anna Salowka, the architecture of each bud is not homogeneous along its axes. At the organ level, we discovered that the mesenchyme surrounding the ventral and dorsal pancreas is distinct (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, along the dorsal pancreas -from the duodenum to the region next to the spleen- specific mesenchyme subsets are selectively enriched (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2 (A) Representative ISS image showing selected genes in dorsal pancreas (DP) and ventral pancreas (VP) at E12.5. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Representative three-dimensional (3D) rendering of light-sheet fluorescent microscopy image (left) and confocal microscopy images (right) of E12.5 pancreas stained with indicated antibodies. Right: Confocal IF images show transverse cryosections of DP at tail (i) and stalk (ii) levels. Hoechst was used as nuclear counterstain. Scale bars, 100 μm. Asterisk indicates approximate position of the spleen.

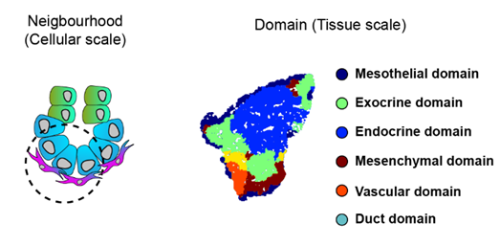

To increase the resolution of our analysis to meso- and micro- scales (Fig. 3), Gabriel Herrera (at the time rotation student in the lab) brough into the project his bioinformatic skills to implement pipelines to analyse the spatial data. What we found is that the tissue is organised in concentrical niches enriched in mesothelial, mesenchymal, exocrine or endocrine cells. When comparing exocrine and endocrine niches, we found that proliferative mesenchyme was preferentially located around acinar cells, whereas another subset, which we termed Mesenchyme (M)-II, was enriched in the endocrine niche.

Fig. 3 Schematics of the spatial analysis frameworks: At cellular scale (left), spatial neighborhoods encompassing the 10 closest cells around each cell were used to calculate cluster pair neighborhood enrichment; at tissue scale (right), tissue areas with similar local cell type composition were clustered to identify tissue domains.

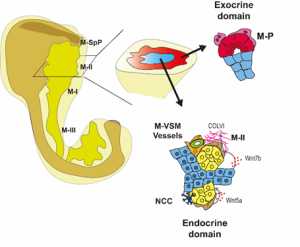

We then focused on the latter association and identified putative Ligand:Receptor interactions between M-II and endocrine cells (Fig. 4). In particular, Wnt5a and Collagen VI molecules caught our attention because of their potential role in creating a niche favourable for endocrine and, specifically, beta-cell differentiation. Consistently, functional experiments using mouse pancreatic explants demonstrated that blocking Wnt5a signaling hampered endocrinogenesis by perturbing the JNK pathway. On the other hand, explants treated with Collagen VI showed a higher number of endocrine cells. By examining human foetal pancreatic tissue, Georgina Goss, a postdoc in the lab, showed that Collagen VI is also enriched around human endocrine cells. Finally, I went on embedding human iPSC-derived endocrine cells in hydrogels containing different ECM mixes, and discovered that Collagen VI, in a conserved fashion, increased the number of beta-cells in the cultures.

To complete our study, we decided to have a glimpse of the adult pancreas. What we found is that different mesenchyme subsets are enriched inside and around islets of Langerhans, ducts and acini. A long-standing question in the field is to track the origin of the adult pancreatic mesenchyme. Our dataset enabled us to fill this gap. Using in silico analysis, we identified fate trajectories connecting the embryonic and adult mesenchyme. Our results suggested that the Spleno-Pancreatic mesenchyme could be one of the origins of the adult mesenchyme which we confirmed using in vivo lineage tracing.

Fig 4: Spatial organization of the pancreatic mesenchyme during embryonic development

What’s next?

Several questions remain open, and several arose during the project. If the pancreatic tissue is carefully distributed, how is that architecture shaped? What signals link epithelial compartments to the formation of their surrounding microenvironment? Our results also raise questions regarding the function of the different levels of organisation: Why does pancreas development need gradients of signalling along the proximodistal axis? It would be interesting to test whether the disruption of that axis causes defects in the separation of the pancreas and surrounding organs. Further research is also needed to understand the function of the secretion of specific ECM components, such as Collagen VI, around exocrine and endocrine cells. In the case of Collagen VI, it would be interesting to investigate how it affects tissue stiffness, as it has been shown that control of the mechanotransducer YAP is crucial for endocrinogenesis. Finally, the spatial organization of the microenvironment during human embryonic development needs further characterization, but using similar approaches we are now beginning to understand it, so if you want to know a little bit more about it, check out the new preprint from the lab5.

Access the article: Torres-Cano, A., Darrigrand, J. F., Herrera-Oropeza, G., Goss, G., Willnow, D., Salowka, A., Ma, S., Chitnis, D., Rouault, M., Vigilante, A., & Spagnoli, F. M. (2025). Spatially organized cellular communities shape functional tissue architecture in the pancreas. Sci Adv, 11(46), eadx5791. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adx5791

References

1. Golosow, N. & Grobstein, C. Epitheliomesenchymal interaction in pancreatic morphogenesis. Developmental Biology 4, doi:10.1016/0012-1606(62)90042-8 (1962/04/01).

2. L, L. et al. Pancreatic mesenchyme regulates epithelial organogenesis throughout development – PubMed. PLoS biology 9, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001143 (2011 Sep).

3. C, C. et al. A Specialized Niche in the Pancreatic Microenvironment Promotes Endocrine Differentiation – PubMed. Developmental cell 55, doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2020.08.003 (10/26/2020).

4. Byrnes, L. E. et al. Lineage dynamics of murine pancreatic development at single-cell resolution. Nature Communications 2018 9:1 9, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06176-3 (2018-09-25).

5. Goss, G. et al. Mesodermal-niche interactions direct specification and differentiation of pancreatic islet cells in human multilineage organoids. bioRxiv, 2025.2012.2013.694117, doi:10.64898/2025.12.13.694117 (2025).

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)