Abigail Tucker: the first to be awarded the BSDB Cheryll Tickle medal

Posted by BSDB, on 1 February 2016

![]() As reported earlier last year, the BSDB has introduced the Cheryll Tickle Medal, which will be awarded annually to a mid-career, female scientist for her outstanding achievements in the field of Developmental Biology. The BSDB is proud to announce the inaugural awardee Prof. Abigail Saffron Tucker. The medal was handed over to Abigail at the BSCB/BSDB Spring Meeting 2016 where she presented the Cheryll Tickle Award Lecture (available on YouTube), and a post-award interview was published in Development.

As reported earlier last year, the BSDB has introduced the Cheryll Tickle Medal, which will be awarded annually to a mid-career, female scientist for her outstanding achievements in the field of Developmental Biology. The BSDB is proud to announce the inaugural awardee Prof. Abigail Saffron Tucker. The medal was handed over to Abigail at the BSCB/BSDB Spring Meeting 2016 where she presented the Cheryll Tickle Award Lecture (available on YouTube), and a post-award interview was published in Development.

Note that this post was first published in the BSDB Newletter 2015 which can be downloaded (together with newsletters of the last 10 years) here.

Background and History

The award is named after Cheryll Tickle (CBE FRS FRSE Hon FSB), an extremely eminent cell and developmental biologist who used the developing limb bud to explore pattern formation in embryogenesis. After her undergraduate studies at Cambridge and PhD work at Glasgow, she worked as a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University, then as a postdoc in the group of Lewis Wolpert at Middlesex Hospital (later merged into UCL) where she studied the morphogen model of digit patterning. This laid the foundation for her subsequent work on the elusive limb polarising factor, mechanisms of limb outgrowth, FGF signalling, HOX gene regulation and snake limblessness. While at Middlesex/UCL, she moved up the ranks from lecturer, to reader and eventually to Professor, and shortly after she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, an acolade which was awarded the same year she moved to Dundee (1998). Cheryll was the first ever Waddington medal winner (1998) and became the first female Royal Society Foulerton Fellow (2000). Currently Professor Emeritus at the University of Bath, she continues to explore diverse limb projects such as the loss of the pelvic fin in natural populations of sticklebacks as well as ectopic bone formation in wounded war veterans.

The award is named after Cheryll Tickle (CBE FRS FRSE Hon FSB), an extremely eminent cell and developmental biologist who used the developing limb bud to explore pattern formation in embryogenesis. After her undergraduate studies at Cambridge and PhD work at Glasgow, she worked as a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University, then as a postdoc in the group of Lewis Wolpert at Middlesex Hospital (later merged into UCL) where she studied the morphogen model of digit patterning. This laid the foundation for her subsequent work on the elusive limb polarising factor, mechanisms of limb outgrowth, FGF signalling, HOX gene regulation and snake limblessness. While at Middlesex/UCL, she moved up the ranks from lecturer, to reader and eventually to Professor, and shortly after she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, an acolade which was awarded the same year she moved to Dundee (1998). Cheryll was the first ever Waddington medal winner (1998) and became the first female Royal Society Foulerton Fellow (2000). Currently Professor Emeritus at the University of Bath, she continues to explore diverse limb projects such as the loss of the pelvic fin in natural populations of sticklebacks as well as ectopic bone formation in wounded war veterans.

The first awardee, Abigail Tucker

The BSDB is proud to announce the first winner of the Cheryll Tickle Medal, which will be awarded at the 2016 BSDB-BSCB Spring meeting in Warwick to Prof. Abigail Saffron Tucker. Abigail obtained her DPhil from Oxford University in 1996 in the lab of Prof Jonathan Slack. She then worked as a post-doctoral fellow at Guy’s Hospital, London, in the labs of Prof Paul Sharpe and Prof Andrew Lumsden. Here she started her interest in embryonic development of the head. She set up her own laboratory as a Wellcome Trust Research Career Development fellow in 1999 in the MRC centre for Developmental Neurobiology at King’s. In 2002 she moved to the department of Craniofacial Development within the Dental Institute at King’s College London as a Lecturer and was promoted to Senior Lecturer in 2007, Reader in 2012 and Professor in 2015. In 2014, she was selected as a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator and leads a research team of 11 people, including an impressive number of past and present PhD students. She has three children, Poppy, Imogen and Max.

The BSDB is proud to announce the first winner of the Cheryll Tickle Medal, which will be awarded at the 2016 BSDB-BSCB Spring meeting in Warwick to Prof. Abigail Saffron Tucker. Abigail obtained her DPhil from Oxford University in 1996 in the lab of Prof Jonathan Slack. She then worked as a post-doctoral fellow at Guy’s Hospital, London, in the labs of Prof Paul Sharpe and Prof Andrew Lumsden. Here she started her interest in embryonic development of the head. She set up her own laboratory as a Wellcome Trust Research Career Development fellow in 1999 in the MRC centre for Developmental Neurobiology at King’s. In 2002 she moved to the department of Craniofacial Development within the Dental Institute at King’s College London as a Lecturer and was promoted to Senior Lecturer in 2007, Reader in 2012 and Professor in 2015. In 2014, she was selected as a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator and leads a research team of 11 people, including an impressive number of past and present PhD students. She has three children, Poppy, Imogen and Max.

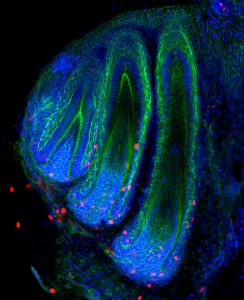

Abigail’s has published over 100 papers on Developmental Biology, many of them in high ranking scientific journals. Her research concerns the development of the head, with particular recent focus on the ear, jaw, teeth and glands, which are all linked during development depending on complex epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. The Tucker group investigates a number of aspects concerning these tissues, including the transcription factors and signalling molecules that control their patterning and shape, their embryonic origins, congenital birth defects relating to them, and how cranial structures undergo repair/regeneration. A further research line of the group investigates how evolution shapes our faces and how Developmental Biology can be used to understand the mechanisms behind evolutionary change. The lab is therefore a host to many different species for study, including snakes, geckos, chameleons, chicks, opossums, and mouse.

Apart from the Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award mentioned before, Abigail has been selected for KCL’s “Supervisory Excellence Award” in 2011, the Anatomical Society’s “Fellow of the Year” Award in 2014, the “BSDB Cheryl Tickle Medal” in 2016 and shortlisted for the “King’s Public Engagement Award” in 2015. She acts as an editor for the Journal of Anatomy and Developmental Dynamics, is a council member for the Anatomical Society, a member of KCL’s Life Sciences Museum management board, sits on the Public engagement committee of the Royal Society of Biology, and is director of postgraduate research at KCL’s Dental Institute. Besides these many scientific and administrative roles, Abigail even finds time for successful public engagement activities including the “Science uncovered evening” at the Natural History museum, the “Summer Science Exhibition” of the Royal Society, the “Cheltenham Science Festival”, giving career talks in schools and providing work experience placements, as well as contributions to broadcasted programmes, such as “Easter Eggs Live” (Channel 4, 2013) and “Your Inner Fish: an Evolution Story” (BBC4, 2015). Read here some of Abigail’s views concerning important questions concerning our field and its future.

Which are the important questions in Developmental Biology?

I love developmental biology, how you can generate a complex structure, such as the head, by combining tissues of different origin and ending up with a coordinated structure. Although we know lots about the development of many structures, there are always more questions being generated. At the moment there is a wave of research trying to understand how gene expression changes result in cellular changes that physically shape tissues and organs. We can say that a mutation in a specific gene causes a developmental defect, such as a cleft palate, but we still don’t always know how that genetic change leads to a cellular change. At the moment we are used to saying, oh that happens due to proliferation or cell death, but now people are starting to look at such cell behaviours much more closely. Personally, I find there are lots of very understudied organs/tissues/processes just waiting to be investigated. I have just started working on the external ear, which has a fabulously complex morphogenesis, but hardly anything is known about it.

Will Developmental Biology remain an important discipline that young researchers should aspire to?

I really hope so. It is a fascinating area and one that the general public are also really interested in. An understanding of Developmental Biology is also essential for understanding cell fate decisions, which is a key part of repair and regenerative biology. From an evolutionary point of view Developmental Biology is also important to provide possible mechanisms whereby evolutionary change can be generated. I have read quite a few papers where proposed mechanisms for evolution of a new structure didn’t make any sense, as the writer didn’t have a good knowledge of how structures normally form during development. From a clinical point of view you can really understand anatomy if you understand how tissues form in the first place.

Which were the key events or experiences in your life that influenced your career decisions and paved your path to success?

I have been lucky in that I always wanted to be a scientist. At the age of eleven I wrote that in 10 years time I would be starting a PhD in biology and I was, although I must admit I thought I would be travelling the world researching primates in exotic locations rather than working in a lab! At University I took a course in Developmental Biology and was hooked. At the time many great names in developmental biology were at the Oxford Developmental Biology Unit: Jonathan Slack, David Ish-Horowicz, Julian Lewis, Phil Ingham, Chris Graham to name a few. I was very lucky to arrive there at that time and it drove me to a PhD and my future career. I have also been lucky to have some really supportive supervisors and mentors over the years, which is essential, particularly while having career breaks and going part time.

What advice do you give young researchers towards a successful career?

I have really benefitted from trying different model organisms throughout my career. I moved from Xenopus to mouse to chick during my PhD and postdocs, which meant I can now use aspects of all these models to answer questions. It’s given me a much broader understanding of developmental biology and lots of flexibility. When moving to an independent career I think it’s important to come up with some real key questions you want to answer in an area you can make your own. Look out for the quirky and take advantage of new technologies but also read the old papers (some very old) as they are often a real font of forgotten information.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)