Cut + Paste: Crick exhibition on the future and ethics of genome editing invites the public to give their opinion

Posted by Alexandra Bisia, on 10 March 2023

On Thursday 23 February I visited the Crick Institute in London to see their new exhibition, Cut + Paste, and to meet the organisers. Cut + Paste is an interactive exhibition that invites attendees to learn about applications of genome editing currently being implemented or those that are being investigated as potential solutions to environmental, food supply, or medical problems facing 21st century humanity. Equally importantly, the exhibition aims to engage visitors, make them think about potential risks in the technology, and ask them for their own opinions.

The exhibition was organised by creative consultancy ‘The Liminal Space’ in collaboration with the Crick’s public engagement team, with Professor Robin Lovell-Badge and Dr Güneş Taylor, researchers at the Institute, serving as scientific advisors.

The exhibition is small, engaging and informative, and is designed to appeal to as wide an audience as possible, in terms of age but also familiarity with the topic. After giving visitors a brief tour of the DNA and its information storage unit, the gene, the exhibition introduces gene editing as a method to introduce precise edits to the genome, both large-scale as well as single-‘letter’ edits. The exhibition then gives an overview of the various applications of genome editing that are already in use and those being investigated with the aim of solving some of the world’s pressing problems. Among some of the topics explored by the exhibition are the editing of plant genes to make plants more nutritious; modifying the genes of livestock to make them emit less methane, a greenhouse gas; curing or treating human diseases such as sickle-cell anaemia; or ‘enhancing’ humans with new characteristics, such as making them resistant to HIV infection or curing deafness.

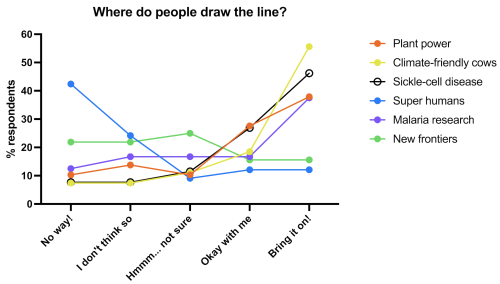

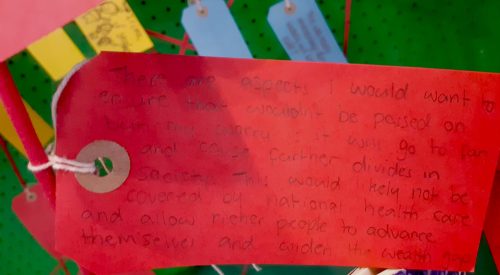

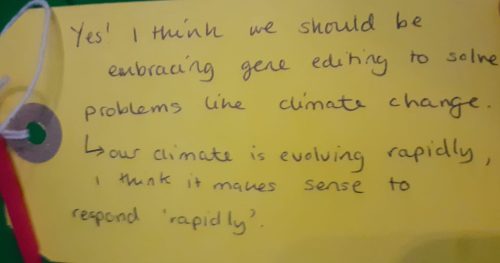

The best thing about the exhibition, in my opinion, is the high degree to which it invites viewers to contribute their opinion. Early on in the exhibition, viewers are asked which traits they’d want to pass on to their children (Science whizz? Sense of humour? Compassion?) and to combine their selection into a ‘gift.’ Later, attendees can read arguments on the potential pros and cons for each of the applications of genome editing and are invited to show how keen they are to see this application come to life by throwing a ping-pong ball into one of five ‘bins.’ Interestingly, but perhaps unsurprisingly, applications directly associated with human genome editing seemed to be more controversial. I had the opportunity to do a bit of my own research on visitors’ attitudes by calculating how popular each application was. At the end of the exhibition, visitors can record their thoughts into a microphone or write their opinion on a note card and hang it up on a ‘web of ideas’ along with others’.

Climate-friendly cows – should genome editing be used to help solve environmental crises?

Sickle cell disease – should genome editing be used to cure inherited diseases?

Super humans – should gnome editing enhance our minds and bodies?

Malaria research – should genome editing be used on entire species to get rid of infectious disease?

New frontiers – should we use heritable human genome editing for challenges that could be solved in other ways?

Visitors to the exhibition are not as ready for editing human genomes to have enhanced traits or for addressing challenges that could be otherwise solved.

I was able to talk to some attendees on the day and ask their opinion. Jaz and Chloe mostly agreed with genome editing for the treatment of diseases and the improvement of human health but disagreed about the risk of gene-edited crops or animals potentially altering the ecosystems they are released into. They both loved the interactive/game-like element of the exhibition. Clearly the exhibition provides a lot of food for thought!

I also had the opportunity to talk with Dr Taylor about the exhibition in more detail, and their involvement with public engagement in the context of scientific research.

For the Cut + Paste exhibition, could you take us through the process from the initial conception to the final exhibition?

Cut + Paste was first conceptualised before the pandemic. When the Crick was first started in 2017, [genome editing] was put forward as a good subject to cover soon [in the Crick’s exhibition space], because it’s timely and it matters. The idea at the time was to have a small trial exhibition, where we tried different concepts to see how the public responded to different ways in which this information could be presented. Then the pandemic put everything on ice. So as we were coming out of the pandemic, it was decided that we would re-engage the project, and develop it into a full-sized, full-year exhibition.

The important point of the starting phase is to have conversations that capture all the things that you think are important and to have some dialogue about “Which of these many different things should we be talking about as a biomedical research institution?” Importantly, one of the big things that happened in the course of this was [that] it went from just being, “Here is an exhibition just explaining what genome editing is,” to becoming not really an exhibition per se, rather a space to engage with difficult ethical questions stemming from genome editing. So you’ll notice that it’s not really pictures of Cas9 and CRISPR everywhere. It’s deliberately designed to be more about those questions than about the technology in itself.

Absolutely. Ok, so, in that vein, how did you choose which specific genetic modification ‘case studies’ to highlight in the exhibition?

There are six case studies, scenarios, and of them, one is about plants, one is about livestock, one is about pests that carry diseases that affect humans, and the other three are all about humans directly. That’s a reflection of the fact that we’re a biomedical research institute. We don’t actually study plants or even livestock [at the Crick]. But it was important to flag them, because we were keen to get across this idea that anything on Earth that has DNA can now be edited using this technology. The potential ramifications of this technology are all-encompassing, and we really wanted people to understand that.

Also people feel quite differently, and much more strongly, about the human scenarios. So, it also functions to bring people into the right headspace to think about it. It’s one thing to think about a plant: “How does that affect food and food supplies?”, and then thinking about livestock, there’s a bit more ethical concern, “What about their welfare?” There’s a bit of a sliding scale, naturally, in that.

What are you hoping will be the major messages and takeaways of the people who attend the exhibition? Do you plan to track responses to questions in the exhibition to assess what attendees’ opinions are and how they may have changed as a result of attending the exhibition?

Exactly. The key information that we’re hoping to get across is that genome editing is a technology for changing DNA, and there are different contexts under which you can use this technology, but the main thing that we wanted was for people to engage. Often people initially think “I’m not a scientist, I don’t know.” We wanted to overcome that, such that people feel empowered and have a sense of agency about these conversations.

The second thing [we wanted to get across] is, of course, an immediate appreciation for the fact that there is a diversity of opinion on, and value in, each of the scenarios that we present. You’ll notice that the scenario cards [in the exhibition, describing pros and cons of each potential genome editing scenario] deliberately have opposing opinions, and that’s important to remember, in this context especially. It’s to make people comfortable to engage, but also comfortable and aware of the fact that some people disagree.

And then of course the final thing is that we have this ‘make your mark’ section where we invite people to vote and write things down and record their thoughts, and as a research institute we will be keeping record of that, and it will potentially feed into statements we will make in the future regarding genome editing and future policy decisions.

You’ve been involved in science communication for several years. What about it do you find exciting and important? What about science communication would you like both the scientific community and members of the general public interested in science to know?

I think that many scientists still think that it’s pointless, and I obviously disagree with that. I was always raised with this idea of the Victorian scientist who does the experiments and then gives the public lectures, so I thought that was completely normal. It wasn’t until I started the PhD that I realised people are very hierarchical in academia, like “Who are you to go out and talk to the public? You don’t have a Nobel prize, who cares?” But, on principle, we are publicly funded. I felt very seriously that I am funded by the public, it’s charity money that’s giving me my salary to do this, so if the public want to know about something, they have a right to know.

Actually, whether I’m talking to a biochemist, or an engineer, or an electrician, there’s not really that much difference. I would classify [all] as public engagement. You talk to anyone outside your field, it’s basically public engagement, because most people don’t know about the finer nuances of your field. It’s been real training for me in how to communicate clearly. And I didn’t go into it for that, but since realising that that’s a side effect, I’ve encouraged as many people as I can to get comfortable doing that. The true challenge in trying to demonstrate mastery of something is to be able to accurately transmit that information in simple terms. And there is no better context under which to do that than public engagement.

The last thing to say about it is, at least in my experience, academia is extremely hierarchical, and that can corrode one’s self-confidence a lot. For me, science communication has been an antidote to that. A different context under which I can practice remembering that I am an expert, of sorts. That’s more of an amorphous benefit, but I think it’s really important because we don’t get much gratification in our line of work. It’s not often that a big experiment works. But it can be so satisfying to have that moment of being able to say “You didn’t understand what DNA was when we started this conversation, and now you asked me a really smart question, so I know you understand.” And that immediate gratification, at least for me, has been really helpful.

Do you have any short- or longer-term plans for public engagement events on any other topics?

I don’t actively plan them. If I get invited to do something, or if somebody wants my opinion, I will give it. I value ‘engagement’ with a little ‘e,’ if that makes sense. For me, the way to have a tangible impact comes from the personal interactions that you have with people. It’s just engagement with a little ‘e’ rather than with a capital ‘E.’ It’s not in the context of an institution, but those are the moments that for me never stop. Someone says “What do you do?” and you say “I’m a scientist,” and then almost inevitably they say “I didn’t do well at school at science,” or “I’m really bad at maths.” For me that’s an opportunity to engage and say “Yeah, me too, but I just really like it.” And to normalise that conversation about science is really timely. The pandemic, if nothing else, proved that there is a moment right now where people really see that science is important, but maybe don’t know how to engage or still feel very much like science is something that scientists do. [But] the reality is, the scientific method – the ability to observe, hypothesise, and rationally interrogate information – is not something that only scientists do. And for me, that’s the heart of any of these things.

The Cut + Paste exhibition is open to visitors Wed 10:00-20:00 and Thurs-Sat 10:00-16:00 at the Crick Institute until December 2nd 2023.

(2 votes)

(2 votes)