A day in the life of a Honeybee lab

Posted by meganleask, on 19 January 2015

Welcome to the Lab for Evolution and Development.

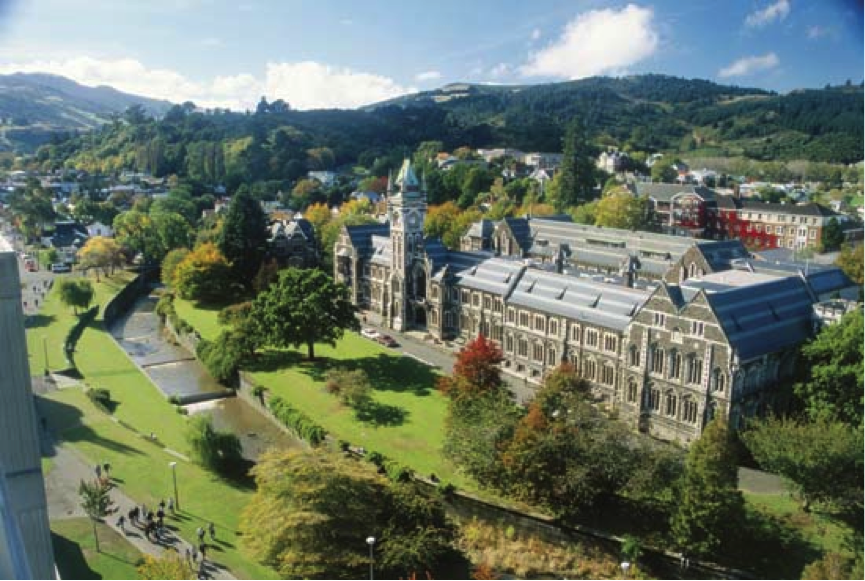

The lab is situated in the deep south of New Zealand in the quaint Scottish inspired little city of Dunedin. 1/5 of the population of Dunedin is made up of students and the University is considered the heart of the Dunedin community. I was a student here for 9 years and I love Dunedin and our lab so much that I decided to stay on in our lab as a Post-doctoral Fellow. Our lab is based in the Biochemistry Department and is primarily focused on answering evo-devo questions using a number of different Arthropods species. We are particularly interested in unraveling the mechanisms that underlie phenotypic plasticity and for these questions we use the Western honeybee Apis mellifera.

View of the historic University of Otago Clock Tower Building, with Signal Hill in the background and the Leith River which runs through the heart of the University.

The honeybee displays some of the most remarkable examples of phenotypic plasticity seen in animals. During larval development of the female honeybee, differential nutrition leads to the development of two phenotypically very different females castes; the queen and the worker honeybees. In addition to this and what was the focus of my PhD research is the ability of the worker honeybee to activate its ovaries upon removal of the queen from the hive (see image below). Ovary activation in the worker honeybee is a process that transforms the quiescent worker ovary into a fully functioning differentiated tissue that can produce drone eggs. Our lab has found that the physiological transformation of the worker ovary involves large-scale gene expression changes and chromatin remodelling for the maintenance of the active worker ovary.

Queen, worker and queen-less worker ovary. Columns depict Queen ovaries on the right, worker ovaries in the middle and the process of ovary activation on the left. As a result of female honeybee caste development, and under normal conditions when the queen is present in a hive, workers are reproductively dormant. During the activation process the worker ovary goes through a number of stages until it finally develops into a fully functioning ovary. Their stage of activation is scored using a four-point scale, modified from Hess (Hess, 1942). Stage 0 is an ovary from a worker that is in a queen-less hive however no activation is seen. In stage 1 the ovary enlarges and begin to differentiate (arrowheads). At stage two oocytes have begun to develop within the ovary and by stage 3 fully developed eggs are present and can be laid as drone eggs in the hive.

Day in the Life of a Honeybee lab: 6th of November

I woke up today to a beautiful spring day, not a cloud in sight, perfect weather for doing some honeybee work. I jumped in my car, drove for 5 minutes to the Uni, found a park and grabbed a coffee on the way to the department. Once I got into Biochemistry and sat at my desk I checked quickly on the phylogeny that I had been running on the server overnight. Success. The best way to start the day. I then rounded up the rest of the lab for a lab photo (we haven’t done one in ages and this blog post was a great excuse). Aren’t we are good looking group?

Next up I asked our wonderful in-house beekeeper Otto to retrieve some honeybees ready for dissection this afternoon. Spring and summer are the busiest times in the lab for dissections as this is the only time when it is feasible to raid the hives and collect enough tissue for the upcoming year of experiments. The whole lab gets stuck in and sometimes we are lucky enough to get new forceps, which is handy when you are out of practice. With so many different projects on the go we need lots of different types of tissue for a number of different experiments including; in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, RNA and DNA analysis and chromatin immunoprecipitation, to name a few. The sheer volume of tissue required as well as creating the active worker hives (by removing the queens) means we have a number of hives situated around Dunedin including a room within the lab that is dedicated to keeping a few small hives of bees. These bees can come and go as they please through plastic tubing that connects the hive to the outside of the building. Otto and Mackenzie however, made the most of the fine weather and went to collect bees from the hives that we have on the roof of the adjacent chemistry building. Unfortunately for me I can no longer participate in the handling of bees as I was stung and became allergic during my PhD. So today I was banished to the microscope room to image some of my immunos I had completed the day before. Imaging is my favourite thing to do at work and it is particularly pleasant and easy on our wonderful confocal microscope.

Mackenzie kindly captured some shots of Otto hard at work. In the images below you can see him checking carefully for the location of the queen, the amount of brood (developing larvae), pollen and honey. Once the hive has been checked and the location of the queen is known worker honeybees can be collected into small containers to take back to the lab.

Images clockwise from top left. Worker honeybees on the edge of a frame. The beautiful array of pollen loaded into the cells of the comb. Otto checking the frames for brood, honey, pollen and the queen. The queen is easily identifiable in the hive because she has a relatively longer abdomen and in this case has had her thorax painted for identification purposes. The smoker, an important piece of equipment for beekeeping. Otto uses the smoker to calm the bees in the hive which reduces their aggression. The middle image shows the entrance to our bee room.

When they returned to the lab they put the bees into the fridge to send them into a peaceful slumber. Once the bees were asleep, Otto, Liz and Mackenzie got to work dissecting out the ovaries of the worker honeybees, collecting them in ice cold PBS, so that I could extract chromatin for my ChIP reactions later on in the afternoon.

Mackenzie dissecting out the ovaries from worker honeybee abdomens.

That afternoon I finished up my chromatin preps and asked around the lab to see what other people were up too. Andrew was doing some enthralling tissue culture in the room next door for protein expression. Liz was working tirelessly on a publication and Mackenzie was finishing off an in situ hybridization in worker ovaries. Before I went home for the day I started running another phylogeny, cleaned my bench and answered some emails, already for another day in the life of honeybee lab.

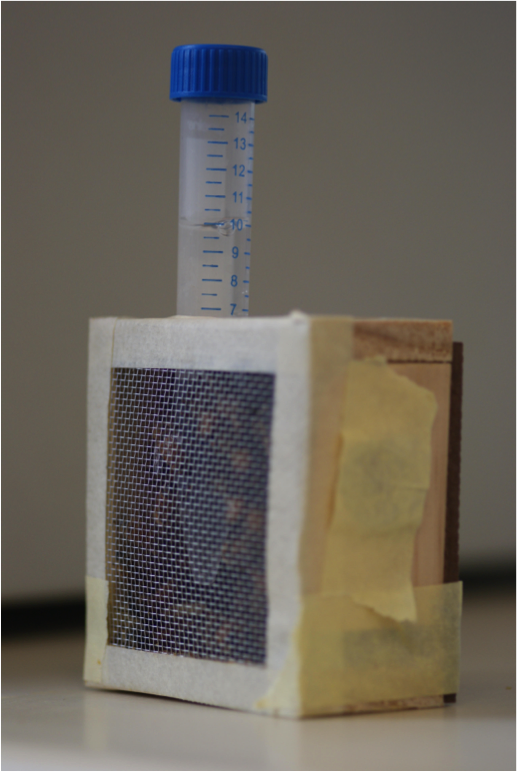

Drug trial cages. These house ~100 worker honeybees. On each side there are caps that contain complete bee food and are supplemented with drug. The bees are also provided with water in a falcon tube and kept at a constant temperature of 34 degrees Celsius in an incubator. To test the function of biological processes in the adult honeybee we feed worker honeybees drug inhibitors over a 10 day period to see whether the drug effects the process of ovary activation. These trials are restricted to the warmer months as we require newly emerged adult bees so that age can be controlled for in these experiments. The very last day of this experiment is an intense day of dissecting and imaging the ovaries from some 800+ honeybees. These images are then scored blindly by two people according the Hess scale seen in image 2 to assess whether the drug has had an effect on ovary activation in comparison to the control cages.

The 6th of November is only a snapshot of the goings on in the Lab for Evolution and Development. Some of the most important experiments happen during summer including RNAi in honeybee embryos and drug trials on adult worker bees, in order to test the biological function of genes and biological pathways. In addition December 2014 will be hectic what with graduation, our Christmas outing and a race to the finish line to complete some of our pending publications as well as the normal day-to-day lab work. As we come into the summer months the lab will be bustling as we welcome in new students and members of the lab focus on getting the majority of their experimental work underway. If you would like to know more or are in our neck of the woods at some point drop us a line we would be more than happy to show you through the lab.

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

(4 votes)

(4 votes)

Dear sir

I am from chungbuk university, south Korea, we undergoing activity experiments on honey bees using herbal drugs, currently using 2 L beaker for experiment and facing more mortality, can you suggest me what kind of cages are suitable for experiment. It would be great help for our ongoing and future experiments.

Thank you

Bala