Divide and conquer. Or don’t divide but still conquer.

Posted by Kalki Kukreja, on 25 January 2025

Behind the paper story for “Cell state transitions are decoupled from cell division during early embryo development“

As embryos develop, their cells perform two fundamental tasks: they divide to populate the developing organism, and they specialize into different cell types—skin cells, brain cells, and more—to carry out a variety of essential functions. In our paper, we set out to explore how the process of cell division influences the differentiation of various cell types during early development.

When I joined Allon Klein’s lab, the team had just published single-cell atlases of zebrafish and frog development (Wagner et al. and Briggs et al. 2018), offering a detailed map of cell states over several hours of embryonic development. Allon and I began brainstorming ways to use them to learn new biology beyond cataloging transcriptional states. We had long discussions on project directions and various fundamental developmental processes we could investigate—genome organization, metabolism, or cell division. As I started reading literature, cell division quickly stood out.

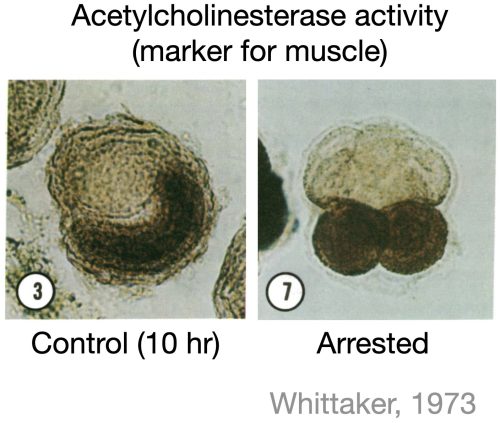

Due to its periodic nature, it has been hypothesized that cell division could act as a clock for developmental events. However, much of the literature does not support the universality of this hypothesis. For instance, studies in ascidian embryos showed that when cell division was blocked at the eight-cell stage, some cells still expressed muscle markers at the correct developmental time, suggesting that cell division was not required for commitment to the muscle lineage (Whittaker et al. 1973, figure below). While several similar studies had tested the impact of blocking division on a few marker genes, a systematic investigation into the role of cell division in forming all major cell types during early development was missing. So, we decided to do just that—in zebrafish embryos.

Zebrafish provided an ideal system for this question because their cells divide and differentiate rapidly in the first day of development (Figure below). Going into my first experiments, I expected to find at least some cell types whose differentiation would depend on active cell cycling. Alternatively, I imagined encountering intermediate “mixed” cell states which I could then follow up on for the rest of my PhD. But, to our surprise, all major cell types differentiated just fine without cell division.

For a while, I was stuck on how to move forward in the project. I spent nearly a year analyzing gene expression changes between control embryos and embryos arrested in the cell cycle. Two key patterns emerged:

- Blood cells differentiated more slowly in arrested embryos, indicating a cell type-specific delay in differentiation.

- Arrested embryos exhibited a characteristic transcriptional program related to cell cycle arrest that was global and independent of cell type.

While differentiation seemed largely unaffected, cell division also controls the proportions of cells across tissues and organs. We asked how blocking division influenced this. One possible outcome was that cell types that normally divide more frequently would be disproportionately reduced in arrested embryos. Alternatively, the embryos might activate a “compensation” mechanism to maintain normal cell proportions.

To answer this, we needed to estimate how many times each cell type has divided under normal conditions—a challenging problem. Emerging lineage tracing tools will likely solve this soon, but we took a computational approach, inferring cell division numbers from single-cell transcriptome data and lineage trees. As expected, cell types that typically divide the most were the most affected by division arrest. However, quantitatively, the effect was less severe than anticipated, suggesting some level of compensation.

Thus, while cell division is not necessary for differentiation, division influences the timing and proportions of cell types.

References

Whittaker, J. R. “Segregation during ascidian embryogenesis of egg cytoplasmic information for tissue-specific enzyme development.” Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences 70.7 (1973): 2096-2100.

Wagner, Daniel E., et al. “Single-cell mapping of gene expression landscapes and lineage in the zebrafish embryo.” Science 360.6392 (2018): 981-987.

Briggs, James A., et al. “The dynamics of gene expression in vertebrate embryogenesis at single-cell resolution.” Science 360.6392 (2018): eaar5780

(4 votes)

(4 votes)