LabCIRS – Learning from mistakes

Posted by Ingo Przesdzing, on 13 December 2016

Biomedical research is experiencing what has been termed a ‘reproducibility crisis’. There is much talk about how we can improve the rigor and robustness of our research to increase its value and predictiveness. Many remedies are being discussed, such as increasing statistical power, reducing bias by improving internal validity, fostering transparency by open data policies, and publication of NULL results, among many others. In general, this debate is about increasing the quality of our research. Errors, mistakes and mishaps negatively impact on quality. In a work environment as complex as experimental biomedical research a substantial number of errors may occur on a daily basis, which can jeopardize the quality of our work, and may waste resources, or even endanger personel. Surprisingly, the issue of errors, and how to avoid them, has not yet received any attention in the current ‘biomedical research waste’ debate.

There is no way for professionals to not make mistakes from time to time. What really makes a difference is how we deal with such mistakes. Often mistakes can even teach you that a certain strategy may not be sufficient to solve a given problem. In any case, we do not want to keep repeating mistakes, so we have to learn how to avoid them. However, while this may work for the person responsible for or witnessing a mistake, this information is lost for the surrounding community if not properly communicated. While most people may consider it as helpful to learn from other’s mistakes, they may not want to admit and communicate their own mistakes in front of others. Potential reasons include just feeling ashamed or concerns that a certain mistake may put the own position at risk. So the question is: How can we facilitate the reporting of errors in an open, non-punitive manner?

Systems to report critical errors and incidents were already in place during World War II in order to improve safety for military pilots. Today, critical incident reporting systems (CIRS) can be found in the energy sector, aviation, or clinical medicine. The basic concept of such CIR systems is that they offer a way to report mistakes and (critical) incidents without the need to reveal the identity of the reporter. While CIRS are mandatory in the context of clinical medicine, structured ways to report errors are virtually unknown in the context of academic preclinical research.

We have therefore developed, tested, and implemented a CIRS for biomedical research. The Department of Experimental Neurology, with approximately 100 students, researchers, and technicians, carries out academic research in preclinical biomedicine. At the moment nine workgroups with different research focus, reaching from spinal cord injury to neuroimmunology work in our department, using techniques like cell culture, microscopy, MRI, animal behavioral studies, molecular biology or biochemistry.

We first encountered the challenge how to handle errors and critical incidents in a structured way in 2012 when we the decided to implement a quality management system to improve the quality and validity of our research. The system we choose as a framework was the ISO 9001:2008 norm, which requested a statement on how we handle critical incidents. During the implementation process we learned a lot about quality management (QM) in general, since QM is very rare in academic basic research. We therefore had to adapt and even invent many features of our QM on the go. The development of CIRS for the laboratory environment is a typical example for this learning by doing approach.

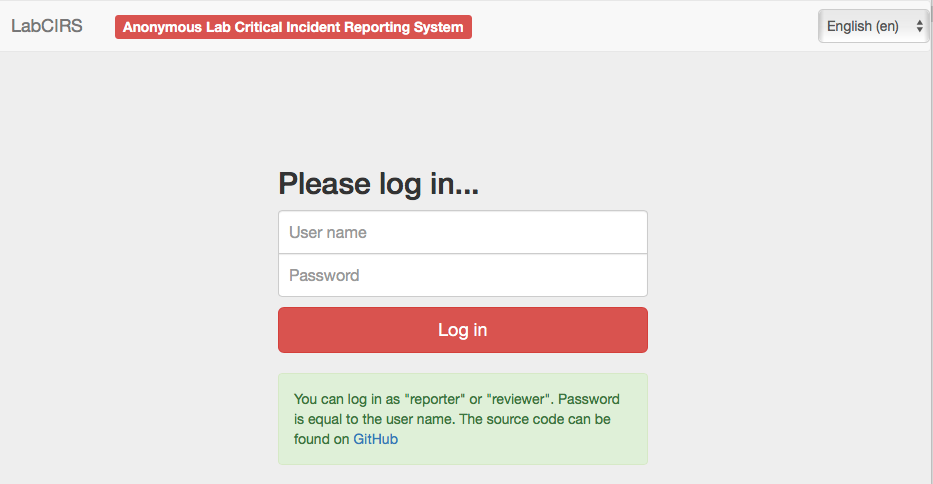

Our first version of an error reporting system was paper based, just a form sheet on our pinboard. While this form already covered all necessary questions, it was almost completely ignored by our staff. Trying to understand the reasons, we found out that the paper version was not convenient and more importantly, not confidential enough. Our colleagues were worried that the reported incident could reveal their identity and may put their position at risk. Acknowledging this obstacle, the idea was born to use an online tool, which does not require user specific information, nor requiring or logging any personal information. Since there was no out of the box system available, which met out needs (anonymous, browser based, structured, but not as complex as a medical CIRS), Sebastian Major, a member of our department designed the LabCIRS from the scratch. The source code and a documentation can be found at github.

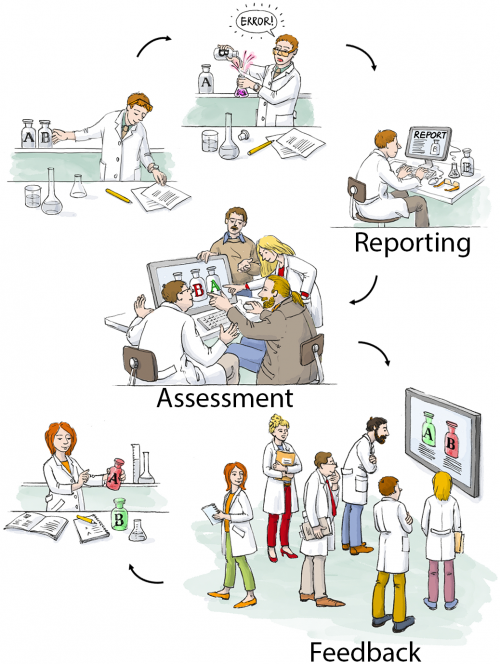

After some fine tuning and beta testing, LabCIRS went online at the end of 2013. This is how it works for the researcher (student, technician, postdoc, etc.): First, one has to log in with a shared login for all department members which does not point to a single user. The system is bilingual (English /German), so depending on their preferences, users can choose the language they feel more comfortable with. After login, the user sees all formerly published incidents and can either search and read through them or report a new incident.

While reporting an incident the reporter can assign a date, describe what happened, and if make suggestions on how to avoid the event in the future. In addition, images can be uploaded, and as a last step, the reporter is asked if the reported incident should be available for all users of the LabCIRS, or reported just to responsible personel.

The reported incident is then checked by a “reviewer” who has privileged access to LabCIRS. This reviewer translates the reported incident and makes sure no personal information is reported. In a next step, the reported incident is internally discussed in our monthly quality meeting with the focus on how the avoid a recurrence of the same incident in the future. Then, if the reporter agreed, it is published inside the LabCIRS, via mail and in addition reported at one of our weekly department meetings.

While it is of course desirable to make all reported incidents available to the public, we found it important to leave this decision to the reporter.

At the very beginning, only about half of the reported entries were cleared by the reporter to be openly published in the department. Over time, however, when it became evident to the reporters that reporting is appreciated and the idea is not to blame anyone, but to learn from mistakes and, if possible, to avoid them in the future, the mindset slowly changed. For more than one year now, all of the reported incidents are cleared for publication. This demonstrates a change in error culture, away from hiding mistakes towards an open discussion and prevention.

Clearly, it is not software which makes people change their minds about quality and error culture, but for us, the LabCIRS was and is a helpful tool helping us in this process.

If you would like to give it try for yourself to check out if this could be useful for you as well, feel free to check it out under http://labcirs.charite.de and download it (or even commit something) at github.

You can find a more detailed report on our LabCIRS in our publication in PLOS Biology.

(2 votes)

(2 votes)

Thanks for posting Ingo – this is an interesting initiative. Can you say anything about the kinds of errors that get reported and whether they’ve actually led to changes in research culture in the institute?

Hello Katherine, most of the reported errors are directly connected to the practical lab work. Looking through the LabCIRS I found a good example from our cell culture lab.

Once, our primary neuronal cells died during a routine measurement. While this seemed to be an isolated problem at the beginning, it turned out that almost everyone was affected, although not everyone was aware of it. The cause of our problem was the PBS, which is the basic component for many solutions in the cell culture. Normally 10x PBS is ordered and then diluted to 1x concentration. For some reason, this time, we did not receive 10x PBS but 1x PBS. Since the bottles looked almost identical and the concentration of the PBS was written in very tiny letters, the person who prepared the 1 x PBS, did not realize that the stock solution already was 1x concentrated, resulting in 0.1x concentrated PBS instead of 1x. When this 0.1x PBS is used, to wash the cells, they just die within minutes.

This was communicated via the LabCIRS.

Reading about that problem at the LabCIRS, other colleagues realized that they also used this PBS as one component in a more complex solution.

In this case, the effect was not as obvious, but could be detected when you knew what to search for. The consequence for our colleagues was to discard the results from this particular experiment and to repeat it.

In a second step we talked about measures to make sure, this will not happen again. We contacted the supplier of the PBS asking for a relabeling of their bottles. I addition we changed our workflow for the preparation of shared solutions.

Coming back to your second question I would say that the implementation of the LabCIRS raised our general awareness. Talking about the reported incidents on a regular base trained us to anticipate and identify possible quality problems in our scientific work trying to find potent measures in order to avoid or at least handle them.