Papa, how do shells twist?

Posted by Joyce Yu, on 12 February 2024

“I want to show children that mathematics is not boring!”

Growing up, Luisma Escudero has always been fascinated by geometry and how patterns are created in nature. That fascination led Luisma to do biology in his undergraduate degree, followed by a PhD in developmental biology, studying the peripheral nervous system development in Drosophila. As a postdoc, his research focussed on morphogenesis. Now, he is a professor and researcher at the University of Seville and Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla (IBiS). His lab combines developmental biology, computational biology, biophysics, and mathematics to understand how tissues are organised in development and disease contexts.

In 2018, his group discovered a geometric shape in epithelial cells that had not been described before — the scutoid. The work attracted a lot of attention from the media. Eventually an editor from a publisher approached Luisma. “They propose that I could write a serious book about how mathematicians, physicists and biologists got together to make the discovery.” recounted Luisma over a Zoom call. “I was very happy about this, but after a while I realised that I was quickly going to get bored writing that book!” Instead, he proposed to the publisher about writing a book with a lot of illustrations, because those scientific concepts need to be visualised for people to understand. But it was out the publisher’s budget to find an illustrator.

In the end, Luisma contacted an illustrator, Raquel Gu, who has experience drawing scientific and mathematical concepts. The two of them started searching for a publisher. Most were not interested, but eventually they found one, who suggested they should focus on writing for children. “We decided that the book will feature me and my children — it was going to be a family book. I was so happy about that decision!”

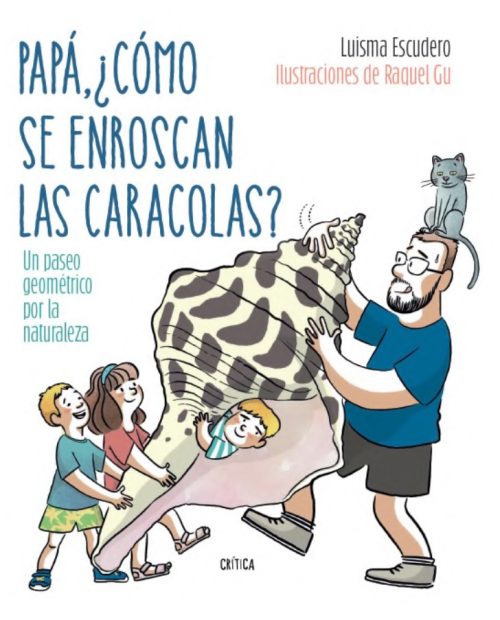

Fast forward to February 2023, the illustrated book “Papá ¿cómo se enroscan las caracolas?” was published in Spain. In the book, Luisma and his family (three curious children and a sarcastic cat that represents Valentina, Luisma’s wife) go on a walk to discover the scutoid shape and other beautiful geometries hidden in nature.

“The book starts off with my children making jokes about my research and me explaining how my research is like a hobby to me,” said Luisma while flipping through the book, which he had right beside his office desk. “Then we go on a walk looking for different geometries in nature. There are 15 chapters. 3 of them are about scutoids. We talked about the more traditional patterns like honeycomb and zebra stripes.” The book goes on to explain more complicated concepts such as the shape of eggs and butterfly wings patterns.

Illustrating scientific concepts

Explaining 3D shapes and patterns in 2D must be challenging, but Luisma said it was all credits to Raquel, the illustrator. “Everything we explain in the book is supported by the drawings. The illustrator used a lot of imagination. For example, she managed to show that scutoids have different neighbours apically and basally in an illustration. I think Raquel hated me when she had to draw all the lava rocks and the tiny fractal cones in the Romanesco broccoli!”

The scientist-illustrator partnership worked well for Luisma and Raquel right from the beginning. They first designed the characters, assigning different colours to every person’s (and the cat’s) speech bubble. For every chapter they met up to discuss all the details, including where the speech bubbles would be and how many times each character speaks. “Raquel also does humour comic strips so she would put jokes in the illustrations. It has been like a lot of fun doing this with her and now we are very good friends. She loves the children, and the children love her. It’s been a very nice collaboration.”

When asked about how they manage to find the balance of communicating the essence of science while making it simple enough for kids to understand and find interesting, Luisma acknowledged that it was a challenge. “We had to keep the story short and make it into a dialogue. I would test my ideas with my eldest child Margarita. I would ask her questions to see what the answer was and what follow up questions she would ask. I had to simplify the explanations a lot in the story, but the scientific rigor is still there. I cannot invent something to make it easier.”

“It has been an adventure!”

To Luisma, publishing the book has been a fun process. “I was really emotional. I never thought I was going to publish a book, nonetheless a children’s book about what I like! Even though I was writing the book while there were a lot of other things going on at work, I was always ahead of the deadline, because for me it was like a hobby.”

Since the book’s publication, Luisma has given talks and attended book signings at book fairs around Spain — Granada, Seville, and the biggest one in Madrid. He also gave presentations at schools and libraries about the book. “The presentations at the library have been a lot of fun because I did a small performance with my children. We prepared a detailed script together and acted out some scenes from the book. My youngest one was only 3 years old when we started doing this.”

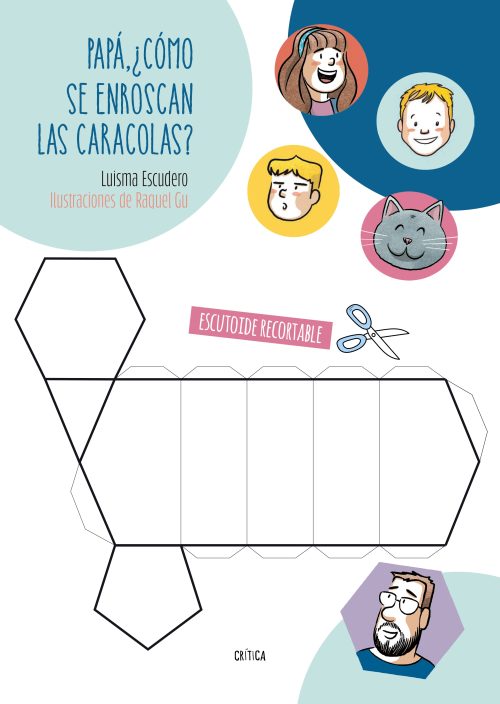

To accompany the book, Luisma designed a cut-out activity to give to children at book fairs and library events.

For the Node readers who would like to make a scutoid at home yourself (with or without children), you can download the high-resolution version.

“I’ll never stop doing science communication.”

Luisma has always been an avid science communicator. Now, he is taking advantage of the popularity of the sctutoid to continue this path. A textbook publisher even asked to feature Luisma and the scutoid discovery in their primary school material. “For me it’s crazy that a paper we published five years ago is now being taught in schools!”

Since the book, Luisma has been working on a few other projects, but he admitted that it has not been as easy as the first book. He has to put more effort to be motivated. He has recently been asked to write and deliver a 5-minute standup comedy script for secondary school students about geometry and other topics like artificial intelligence.

“I feel like when scientists do science communication, they can really make a change and get more children and adults interested in science. When I was in the UK, I felt that the importance of science is more valued. There are research charities, lots of TV programmes about science and private institutions that fund research. Here in Spain, it’s not the same. One of my wishes when I came back to Spain 14 years ago was to get people more into science.”

Translating the book to other languages

Luisma is actively trying to find a publisher in the UK. “A lot of people asked me if the book is in English. That’s why I’m trying to get the interest of some UK publishers. Nothing in the book is very local to Spain and it’s about nature so it shouldn’t be too difficult to translate.”

Wouldn’t it be great for kids from non-Spanish speaking backgrounds to enjoy Luisma’s book and learn to appreciate the hidden geometries in nature too?

Bridge of Sighs, Cambridge, UK:

“In developmental biology people say that epithelial cells are the building blocks of an organism. I also have more or less 100 kilos of construction blocks — they are the Spanish version of Lego, called Tente. I played with Tente as a child to the point of almost becoming a professional!”

(2 votes)

(2 votes)