Peer Review Week 2022: Research Integrity

Posted by Katherine Brown, on 22 September 2022

This week (September 19-23) is Peer Review Week, and the theme this year is “Research integrity: creating and supporting trust in research”. This is a topic very close to Development’s heart – as a key journal for the community we recognise the importance in ensuring, to the best of our abilities, that our papers are trustworthy and we pride ourselves on publishing content that stands the test of time.

I thought it might be interesting for readers of the Node to find out a bit more about what we do at Development to try and protect the integrity of the scientific record. You can also hear more about The Company of Biologists’ activities on this front over on the Company twitter feed, where we’re spotlighting some of our activities and the people behind them.

Research integrity issues come in many flavours, from unreported conflicts of interest and authorship disputes through to plagiarism and data manipulation. And in the almost 14 years (wow, can it really be that long?!) that I’ve been in the publishing business, we’ve seen people trying to cheat the system in ever more elaborate ways – from papermills to fake peer review. It’s profoundly depressing that a publication can be so important to someone’s career that they might go to such lengths to fake one, but somehow this is the world in which we find ourselves.

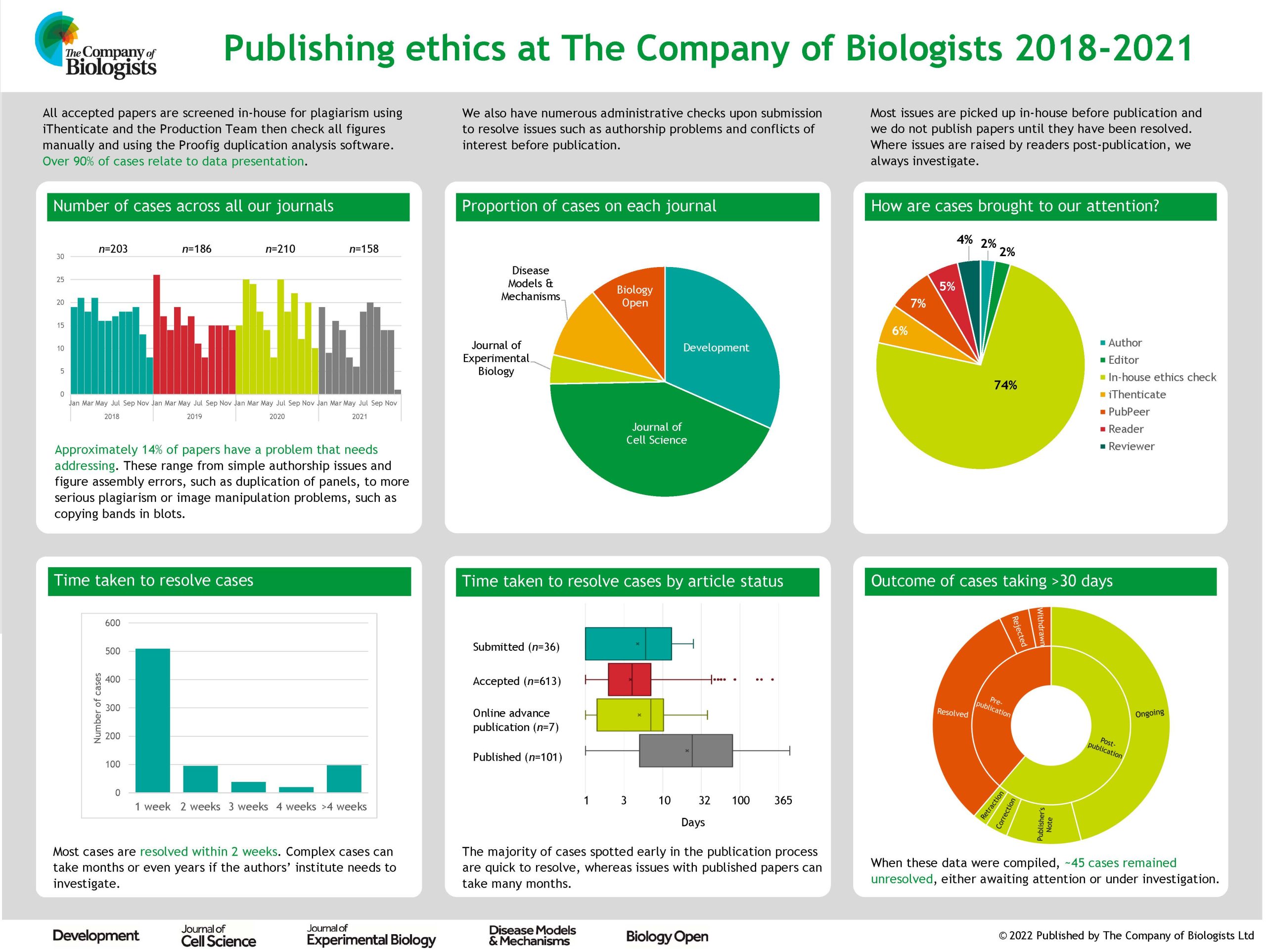

Fortunately, we don’t encounter that many problems at Development, and those we do can generally be resolved without too much difficulty (though I have been threatened with legal action for libel on at least two occasions). So what are the main kinds of issues we do have to deal with, and what processes do we have in place? The vast majority of cases we handle are to do with data presentation – blots that have been cropped, spliced or otherwise altered, images that are duplicated between figures and so on. In most cases these are picked up by our in-house acceptance checks. Our production team screens all figures for potential issues – both by eye and using the Proofig software, which picks up full or partial duplications both within and between figure panels. Where potential issues are detected, these are passed on to our ethics team (production editors trained in handling ethics cases) who communicate with the authors to understand and – hopefully – resolve the problem. Fortunately, most of these issues are the result of honest error on the part of the authors and can easily be fixed prior to publication. Where the case is more complicated, this is usually where I get involved and where, as appropriate, we may need to communicate with the authors’ institution to initiate a wider investigation. We do not publish papers until we are as confident as we can be that the data behind them are trustworthy.

Of course, our processes are not perfect and I’d be lying if I pretended that Development has never published a paper with image integrity issues. Post-publication, we are sometimes alerted to potential problems by readers; we’re grateful for these reports and we do always investigate . This can, however, take a long time, particularly where we need the institute to investigate, and it’s not always possible to reach a definitive conclusion on the integrity of the work, especially in cases where the paper is very old and original records may not still be available. We generally try to alert readers to potential problems with a paper even before an investigation has concluded, and – where problems are confirmed – we then act to correct the literature or, in severe cases, to retract a paper.

While data presentation problems represent the bulk of the integrity issues we have to handle, they are not the only ones. We also screen all accepted papers for potential plagiarism using the iThenticate software – in most cases, any text copying is minor and we can work with the authors to ensure that the original source is appropriately cited. We occasionally have to handle authorship disputes, though we try to ensure that authorship is appropriately attributed at an early stage using the CRediT taxonomy and by requiring all authors to confirm any changes to authorship that might occur while a paper is under consideration with us. Fortunately, Development has not been a big target for papermill papers, but my colleagues at Biology Open have encountered their fair share of papermill submissions and now have rigorous processes in place to try and identify and exclude them.

Most of what I have outlined above relies on the work of our in-house staff. But this post was prompted by Peer Review Week, so how does peer review help to ensure research integrity? In some cases, referees alert us to issues such as possible image manipulation or inappropriate use of statistics and we’re hugely grateful to our dedicated referees who pick up these problems at an early stage in the process. But more generally, I would argue that the process of detailed peer review helps to identify potential flaws in and caveats with a paper, and gives authors the opportunity to address these prior to formal publication. I’m not going to claim that this process is anything close to perfect, but I do believe that most papers are improved by peer review and that the final product is often more rigorous, better controlled and hence more trustworthy than the initial submission. As we look to the future of publishing and consider new models, it’s worth remembering that – given the vast sums of taxpayer and charity money that go towards funding science – we need systems in place to ensure research is disseminated in a responsible way. Peer review and journal publication may not be the only way to achieve this, and for sure it has its limitations, but I have yet to be convinced that there is a better one!

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)