Scientists identify new puberty-promoting genes

Posted by the Node, on 5 November 2019

Press release from Development. You can also read the associated Research Highlight for this article.

A team of neuroscientists led by Professor Christiana Ruhrberg (UCL, UK) and Professor Anna Cariboni (University of Milan, Italy) have found two molecules that work together to help set up the sense of smell and pave the way to puberty in mice. These findings, reported in the journal Development, may help our understanding of why patients with the inherited condition Kallmann syndrome cannot smell properly and cannot start puberty without hormone treatment.

Aficionados of 1990s jazz and fans of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks might remember the distinctive contralto vocals of “Little” Jimmy Scott. Jimmy’s naturally high singing voice was caused by a rare genetic disease, known as Kallmann syndrome, which affects about 1 in 30,000 males and 1 in 120,000 females.

Kallmann syndrome is caused by the lack of a hormone that stimulates the brain to produce signals needed to reach sexual maturity. As a result, people with the condition don’t go through puberty and instead retain a child-like stature, no sex drive and underdeveloped genitals. Currently, the most common treatment is hormone-replacement therapy to bypass the brain and kick-start puberty. Unlike similar reproductive conditions, Kallmann syndrome patients also have no sense of smell – a tell-tale sign of this particular disorder.

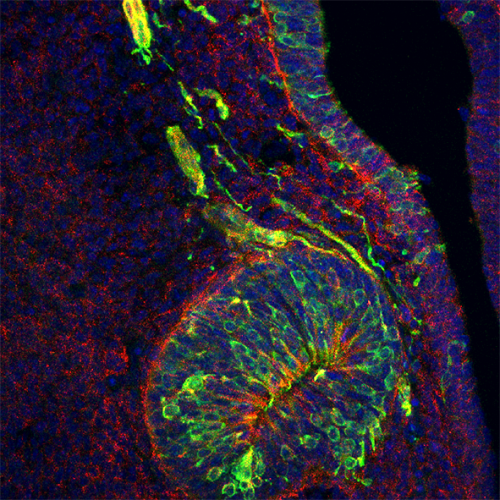

Now, research has identified two molecules, called PLXNA1 and PLXNA3, that might be linked to the condition. Scientists have found that both molecules are present in nerves that extend from the nose into the brain of developing mice. These nerves transmit signals essential for the sense of smell and also guide hormone-secreting nerve cells from their place of origin in the nose to their destination in the brain, where they regulate the onset of puberty. The study has revealed that both types of nerve are not wired properly when PLXNA1 and PLXNA3 are absent in developing mice. Consequently, the brain regions that process smells are poorly formed and the brain also lacks the puberty-promoting nerve cells – the same symptoms shown by Kallmann syndrome patients.

“By studying the mouse as a model organism, we have identified a pair of genes that can cause an inherited condition with symptoms similar to human Kallmann syndrome. This is an important finding, because the nerves that convey our sense of smell and that guide the puberty-inducing nerve cells arise in a very similar way during the development of mice and humans whilst they are still in the womb,” explained Professor Christiana Ruhrberg, who led the UK team.

This research gives hope to patients with an unknown cause of Kallmann syndrome by testing for defects in the PLXNA3 gene together with PLXNA1, which has been previously implicated. The lead author from the University of Milan, Professor Anna Cariboni added, “Although Kallmann syndrome can be treated with hormone injections if diagnosed early, knowing the underlying genetic causes can make a huge difference to speed up diagnosis and give treatment to the right patients at an earlier time.”

The full study, “PLXNA1 and PLXNA3 cooperate to pattern the nasal axons that guide gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons” appears in the journal, Development.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)