Tweaking a gene can remind cells of their ancient roots

Posted by Brent Foster, on 3 January 2024

What is this?

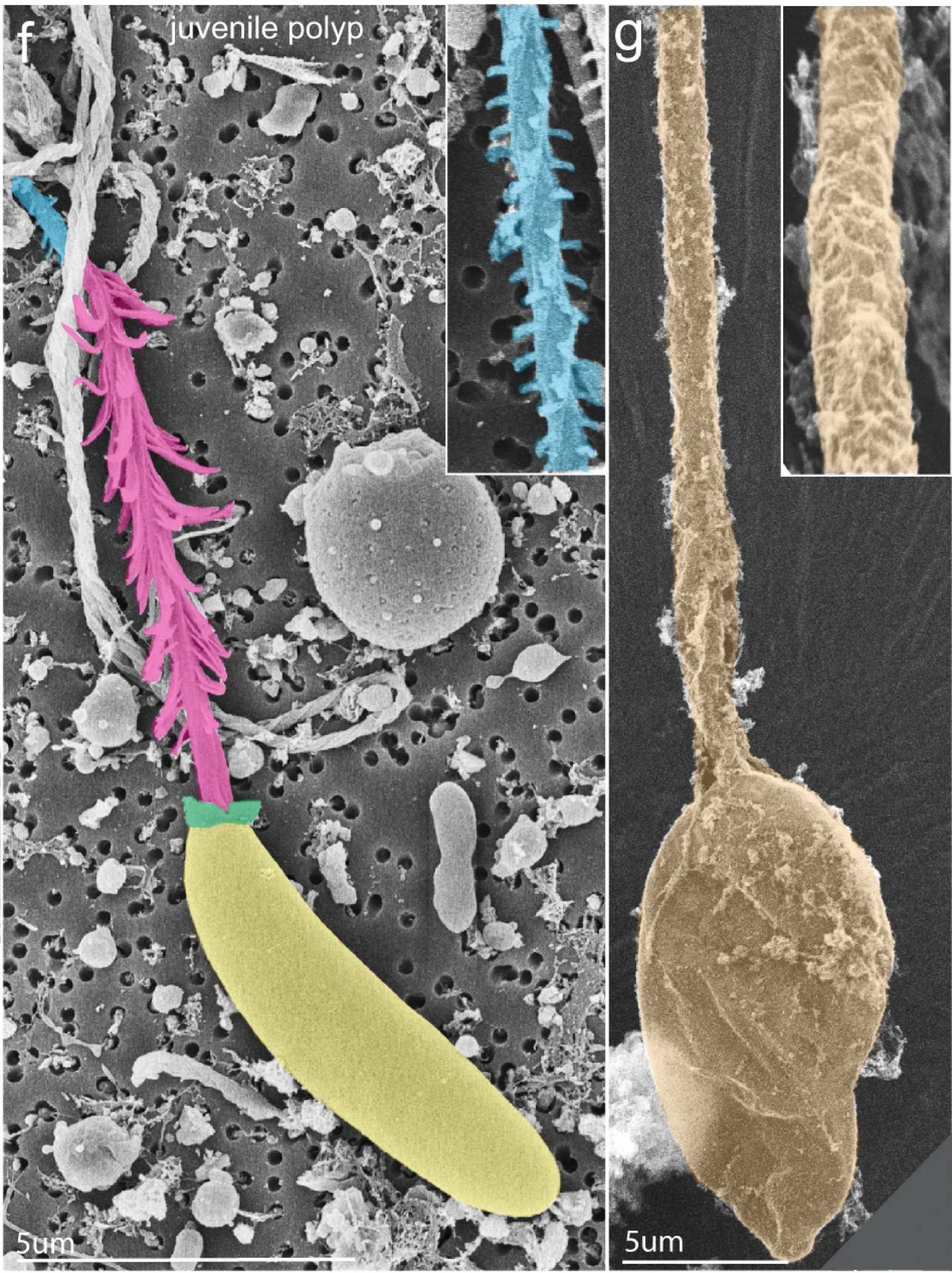

A sea anemone stinging cell (F; left panel) and change in cell identity following the knockout of a gene called NvSox2 (G; right panel).

How was this taken?

With a Scanning Electron Microscope. Images are pseudo-colored to highlight characteristics of these cells.

What does it do?

Sea anemones have various stinging cells, called cnidocytes, with different functions such as piercing prey for feeding or sticking to surfaces so they don’t get swept away by ocean currents.

Why should people care about this?

Piercing cells come in over 30 different sizes and shapes, all of which were thought to share a single “piercing” ancestor. But at some point in the starlet sea anemone’s evolution, a gene called NvSox2 silenced the molecular decisions that led stinging cells to become “sticky” and instead instructed them to become a specific type of “piercing” cell (F), effectively inventing a new cell type.

When NvSox2 is disabled, these “piercing” cells are restored to their ancestral “sticky” identities (G) that have been forgotten in this particular anemone’s long evolutionary history.

These results suggest that single-gene switches driving cell fate have been around for a long, long time and provide a flexible molecular mechanism for animals to adapt to new and changing environments as needed to survive. It’s plausible — maybe even likely — that other types of “piercing” cells have a similar gene-induced amnesia blocking cellular memories of a distant past.

How would you explain this to an 8-year-old?

Sea anemones (pronounced “uh-neh-moh-nees”) don’t look like you and me. They’re related to jellyfish and have special stinging cells. If you’ve ever been stung by a jellyfish, you know that can hurt!

These are pictures of two cells that come from a sea anemone. Someone has colored the cells for us so we can see them better. They’re very different from each other. Can you see how they’re different?

The smooth yellow cell on the left shoots pointy darts into the sea anemone’s food so it can eat. The dart is colored pink and blue in the picture.

The tan cell on the right has large, sticky strings that keep the sea anemone from being washed away.

When these cells are young, they’re not sure if they’re supposed to shoot small pointy darts or large sticky strings when they grow up. Do you know what you want to be when you grow up? How do you know what to choose?

These cells are told what to do with an on-off switch. When the switch is flipped on, the cell forgets how to be large and sticky and looks like the small pointy cell on the left. That’s what this sea anemone normally does. But when scientists turn the switch off, the cell suddenly remembers it should be large and sticky like the cell on the right.

Wouldn’t you like to have a switch to help you remember something that you forgot?

Switches like this can teach us how animals invent new cells. It also shows us how cells store old memories that might help them survive through hard times. When something works, you don’t want to forget it!

Where can people find more about it?

This paper was featured on Nature Communications Editors’ Highlights page. You can find the full-length article here.

Check out other ‘Show and tell’ posts and how about writing one yourself?

(1 votes)

(1 votes)