The people behind the papers – Sungwook Choi

Posted by the Node Interviews, on 13 March 2019

This interview, the 59th in our series, was recently published in Development

The control of timing in development is crucial, both within and between tissues. Heterochrony involves shifts in the rate of development of some tissues relative to others, and although the first heterochronic genes were identified in Caenorhabditis elegans in the early 1980s, their role in inter-tissue developmental coordination is still not completely understood. A new paper in Development tackles this problem with an analysis of the role of lin-28, a key heterochronic gene, in worm fertility. We caught up with Sungwook Choi, first author and recently graduated PhD student in Victor Ambros’ lab at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, to find out more.

When did you first get in to science, and biology in particular?

I have been interested in biology ever since high school. I remember, at that time, being intrigued by the fact that each cellular compartment has distinct functions. I majored in life sciences during my undergraduate studies and focused on plant developmental biology during my Master’s degree.

Why did you decide to make the transition from plant to animal development?

Studying plant biology – in particular the biosynthesis of jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis – gave me the opportunity to be exposed to basic molecular techniques and genetic analysis. Later, when I started my graduate studies in University of Massachusetts (UMass) Medical School, I became interested in small RNA biology. I was fortunate enough to join the laboratory of Victor Ambros and learned that microRNAs, such as lin-4 and let-7, are key regulators of animal developmental timing. Since then, I have expanded my studies beyond microRNAs to include various genetic factors that regulate the timing of animal development.

How did you find the other transition – moving from South Korea to the USA?

It was quite a smooth transition. Although language barriers were inevitable at first, I met many nice people who helped me inside and outside of the laboratory. Also, I greatly enjoy and appreciate the international environment that UMass Medical School fosters through its inclusion of people with different nationalities from diverse cultures.

Before your paper, what was understood about lin-28‘s role in coordinating developmental events?

lin-28 was first identified as a developmental timing regulator in C. elegans by Victor Ambros and Bob Horvitz in the 1980s. The loss of lin-28 causes precocious hypodermal development in larvae and its function has mainly been studied in this context. In particular, many studies have elucidated the genetic relationship of lin-28with other developmental timing regulators such as lin-4, let-7, hbl-1 and lin-46. This genetic regulatory network is called the ‘heterochronic pathway’. In terms of inter-tissue regulation, a 2016 study from Gary Ruvkun’s lab showed that the heterochronic pathway genes act in the hypodermis to regulate mTORC2 signalling in the intestine.

Can you give us the key results of the paper in a paragraph?

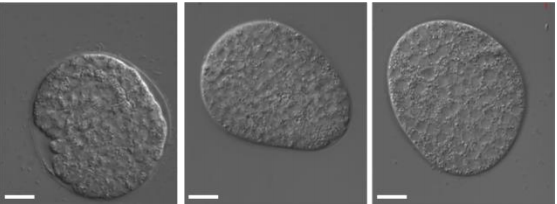

We first looked at why lin-28 loss-of-function mutants exhibit reduced fertility. We found that somatic gonadal structures of the mutants are abnormal, which negatively affect the reproductive process, especially spermathecal exit and ovulation. Then, we asked how lin-28 regulates somatic gonadal structure. By genetic epistasis and tissue-specific rescue experiments, we found that the hypodermal, not somatic gonadal, function of lin-28 in controlling developmental timing is crucial for somatic gonadal development. Therefore, our data indicate that timely hypodermal development guaranteed by lin-28function is essential for somatic gonadal morphogenesis.

Timely hypodermal development guaranteed by lin-28 function is essential for somatic gonadal morphogenesis.

Your data suggest that lin-28 affects somatic gonadal morphogenesis cell non-autonomously: how might an RNA-binding protein act from a distance?

Our data implies that the downstream targets of LIN-28, such as let-7 and lin-46, are still in the hypodermis, not in the somatic gonadal tissues. Therefore, LIN-28 binding to its target RNAs probably happens in the hypodermis. What we have not yet identified is the exact mechanism by which hypodermal precocious development can talk to somatic gonadal morphogenesis. We speculate that there might be actual signalling molecule(s) from the hypodermis to somatic gonad, and/or perhaps physical contact between two tissues could be aberrant in lin-28loss-of-function mutants.

When doing the research, did you have any particular result or eureka moment that has stuck with you?

When I tried to identify the physiological causes of infertility of lin-28(lf) mutants, I didn’t know where to start. Around that time, I went to the Boston Area Worm Meeting and heard the presentation from Erin Cram’s lab about ovulation and spermathecal exit of C. elegans. I came to the realization that lin-28(lf) mutants showed defects in spermathecal exit and from then on, I analysed the mutants focusing on aspects of somatic gonadal development.

And what about the flipside: any moments of frustration or despair?

For me, the frustrating moments about research are not the times when I disprove my research hypothesis. What is most frustrating for me is when established protocols or techniques are not working as expected for my experiments for reasons that I do not understand very well. However, I kept trying to analyse the technical challenges and to enjoy the process of problem solving as a researcher.

Congratulations on getting your PhD last August – what’s next for you?

I haven’t completely decided yet. I am interested in several areas of research including those that are more clinically relevant. Regardless of the topic, I want to do research that is necessary for the progress of the field, even if it may not be particularly fancy.

Finally, let’s move outside the lab – what do you like to do in your spare time in Worcester?

I like Worcester very much. There are many local restaurants and pubs in Worcester, and some famous diners, which I often visit for breakfast. Other than that, I enjoy Worcester’s plentiful cultural resources, like the diverse exhibitions at the Worcester Art Museum and the concert series in the downtown area.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)