The people behind the papers – Takanori Wakatake & Ken Shirasu

Posted by the Node Interviews, on 23 July 2018

Parasitic plants are fascinating and agriculturally relevant organisms that rely for their success on the haustorium, a specialised root structure that invades host root vasculature to derive nutrients and water. A recent paper in Development addresses the developmental origins of these crucial structures in the facultative root parasite Phtheirospermum japonicum. We caught up with first author Takanori Wakatake and his supervisor Ken Shirasu, Group Director at the RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science in Yokohama, to find out more about the story.

Ken, can you give us your scientific biography and the questions your lab is trying to answer?

KS After I got a bachelor’s degree in agricultural chemistry at the University of Tokyo, I moved to University of California, Davis, where I got a PhD degree in Genetics. My PhD thesis was on how a parasitic bacterial pathogen transfers its DNA to the host plant. As a Postdoc at the Salk Institute, I studied how plant immune signals are potentiated. Then I moved to The Sainsbury Laboratory, UK, where I continued to work on plant immunity identifying signalling components. After nearly 18 years of study abroad, I went back to Japan to open a new lab at RIKEN where I started working on parasitic plants. The main theme of our lab is to understand how plants defend themselves against pathogens and how pathogens overcome it. We work on various pathogens including bacteria, fungi, nematodes and parasitic plants, but often realize that they use similar strategies to manipulate host plants.

Takanori, how did you come to join the Shirasu lab?

TW After I made a decision to study plant science at the graduate school of the University of Tokyo, I was thinking which laboratory I should join. There were two main reasons why I chose Ken’s lab. 1) It is in RIKEN, outside the University of Tokyo. I believed that changing environments would help me to build my identity as a scientist. 2) The term “immunity” sounded cool to me because I was interested in pharmacology when I was an undergrad. I eventually became interested in arms race between plants and pathogen. What Ken suggested to me during the first interview, however, was to study parasitic plants, as pathogens. I decided to work on parasitic plants, because I wanted to do something unique.

As far as I can tell, your paper is the first Development has ever published on the development of parasitic plants! What fascinates you about these organisms?

KW & KS How exciting! Parasitic plants are the plants that have evolved to attack own kinds. They do not infect own roots nor members of the same family. Thus, they are able to perceive host plants, which are very similar to themselves, as non-self. How they can differentiate own species from others? And, for infection, they invented a new organ called haustorium, which provides a totally new function. How did plants do that? Haustorium was independently evolved at least 12 times so it should not be so difficult. They must have modified a common machinery so following developmental stages of haustorium we may find some clues.

Can you give us the key results of the paper in a paragraph?

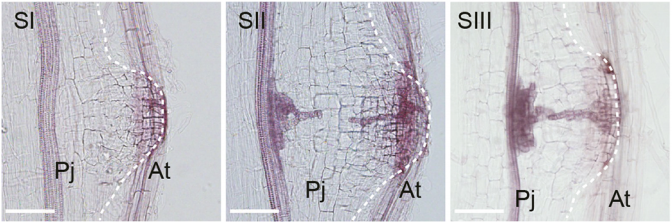

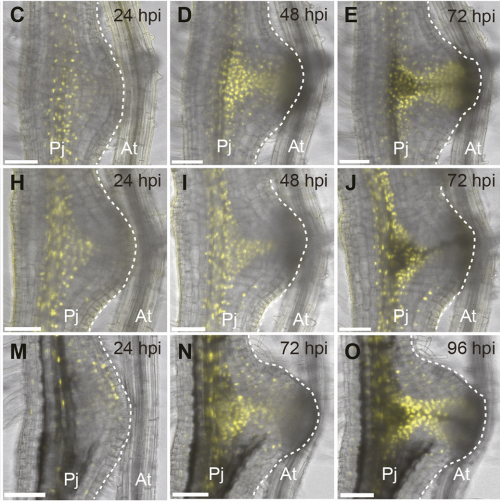

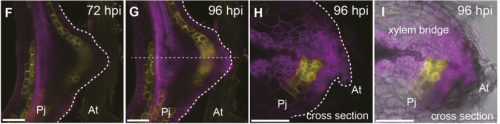

KW & KS In the paper, we demonstrate that cells in the various layers of the root tissues are reprogrammed and collectively establish a new organ upon host perception. In particular, epidermal cells differentiate into specialized cells to penetrate host tissues. Other various cell types differentiate into vascular meristem-like cells to pave the way to connect parasite vascular and host vascular system for nutrient transfer. This is quite different from known developmental processes such as lateral root and nodule formation. This work also represents a high plasticity of plant roots.

Have you got any ideas about the pathways by which the inductive signals control cell fate transitions in a localised manner in the parasitic root?

KW & KS We are currently working on a putative HIF receptor we identified. We aim to elucidate the signalling pathway from HIF perception to local induction of the YUC3 gene, which encodes a key auxin biosynthesis enzyme to initiate haustorium development.

Does your work have any implications for how to combat parasitic plants in agriculture?

KW & KS Not immediately. However, once we understand how haustoria are made, we may be able to block the process. Thus, our work set the fundamental base for the future study to dissect the process.

When doing the research, did you have any particular result or eureka moment that has stuck with you?

KW My favourite experiment in the paper is the lineage tracing using the CRE-Lox system. Initially I thought, based on marker analysis, that various cell types actually change cell fate and differentiate into procambium-like cells. To demonstrate this possibility clearly, I needed a lineage tracing experiment during haustorium development. I designed the CRE-Lox system and made a number of constructs. After many trials, I finally got the result indicating that cortex layers differentiate to procambium-like cells. It was a very satisfying moment.

And what about the flipside: any moments of frustration or despair?

TW At first, I envied the researchers who work on the established model organisms. They can easily access to mutant collections, transformation lines, complete genomes, etc, but now I am fine with our situation and try to think about what we can do. I believe new technologies such as CRISPR and magnetfection will drive the research in non-model plants.

What next for you after this paper?

TW Currently, I am trying to wrap up another paper about auxin flow and xylem bridge formation in the haustorium. After that, I would like to challenge in a new research field.

And where will this work take the Shirasu lab?

KS Intrusive cells are the interface between the parasite and host. They need to deal with host immunity system and find location of host xylem. There must be many signals going by between parasites and hosts. We aim to identify those signals.

Finally, let’s move outside the lab – what do you like to do in your spare time?

TW In general, I like listening nice music, playing games, and watching football games. Recently, I am into watching films and learning cinematography. I am also studying spices for cooking.

KS I enjoy cooking at home. I think that cooking is a creative experience, which makes me excited. It’s more like planning and doing experiments, and at the same time I can feed my family! Vegetables are coming from my small vegetable garden, where I combat a lot of pathogens! So I can do some plant immunity studies there, too!

Induced cell fate transitions at multiple cell layers configure haustorium development in parasitic plants

Takanori Wakatake, Satoko Yoshida, Ken Shirasu

Development 2018 145: dev164848 doi: 10.1242/dev.164848

This is #47 in our interview series. Browse the archive here.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)