Mapping the cardiac neural crest in the frog’s heart

Posted by saintj, on 27 April 2011

The Node’s staff asked me to write a short “behind the scenes” on our paper just released in the May 15 issue of Development, “Cardiac neural crest is dispensable for outflow tract septation in Xenopus” http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.061614

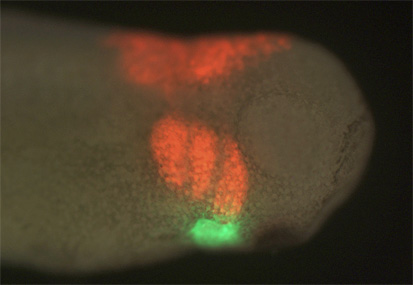

In the summer of 2008 when Dr. Young-Hoon Lee joined my laboratory from Chonbuk National University for a sabbatical we discussed a number of potential projects, and very quickly decided to analyze the contribution of the neural crest to the cardiovascular system in Xenopus laevis. This was a project that we considered several years earlier when Dr. Lee was a postdoc in my lab, but at the time Young-Hoon opted for a different line of research. To address this question we started using the lipophilic dye DiI to label the putative cardiac neural crest in neurula stage embryos. We found that the label cells were consistently excluded from the outflow tract septum. We were a little skeptical about this result, because of what we know of the cardiac neural crest in other species, but mostly because only a small number of neural crest cells is being labeled by DiI injection, and we could not exclude the possibility that unlabelled neural crest cells were contributing to the outflow tract septum. We then decided to move to a tissue transplantation system, where entire segments of the neural crest from RFP-labeled embryos were grafted onto an unlabeled host embryo. These experiments are not trivial and I have to give credit to Young-Hoon for his persistence and exceptional technical skills. Again in these experiments RFP-labeled neural crest cells were exclusively confined to the aortic sac and arch arteries and never populated the outflow tract cushions, confirming our initial observations using DiI. Consistent with these observations, upon cardiac neural crest ablation the outflow tract and the spiral septum developed normally and expressed the molecular markers specific to these lineages. This was a surprise. In chick and mouse the cardiac neural crest provide the separation for the systemic and pulmonary circulations at the arterial pole, remodeling the outflow tract into two vessels by forming the aorticopulmonary septum. In zebrafish where there is no separation between both circulations cardiac neural crest cells contributes myocardial cells to all regions of the heart. In Xenopus we were expecting to find something that was in between fish and amniotes. This is not the case – in frogs cardiac neural crest cells stop their migration before entering the outflow tract. Our next challenge was to determine the embryonic origin of Xenopus outflow tract septum. We were greatly helped in this quest by a recent study from the group of Michael Kuhl at Ulm University (Germany) that carefully mapped the cardiogenic lineages in Xenopus (Gessert and Kuhl. 2009. Dev Biol 334: 395-408). By transplantation of GFP-labeled regions of the cardiogenic mesoderm we found that the septum was derived from the second heart field, presumably by epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation of the endocardial cells lining the cardiac cushions.

The picture below shows a lateral view of a host Xenopus laevis embryo after transplantation of both an RFP-labeled neural crest graft (red) and a GFP-labeled second heart field graft (green).

How to explain these differences in the deployment of cardiac neural crest across species? With a single ventricular chamber the separation of the pulmocutaneous and systemic blood is incomplete in frogs. Therefore a possible explanation is that in species that have an evolutionary need for a fully divided circulation the neural crest was recruited into the outflow tract septum to help complete the separation of both circulations at the arterial pole of the heart.

Lee, Y., & Saint-Jeannet, J. (2011). Cardiac neural crest is dispensable for outflow tract septation in Xenopus Development DOI: 10.1242/dev.061614

(6 votes)

(6 votes)

This is also another occasion to remind ourselves that evolution is not a succession of “improvements” that occur in a straight line. Organisms hit upon different workarounds for the same and new physical challenges, depending on what is in their toolbox already. Hence co-option of genes, but also hence this elegant demonstration of a different solution to a particularly amphibian problem.

Thanks for the behind-the-scenes look!