Publishing ‘dirty’ data

Posted by Katherine Brown, on 22 May 2012

How much does it matter that the images we publish are neat and tidy? It’s a question I’ve been dealing with over the past couple of weeks, and I wanted to share some thoughts. Here at Development, as at many journals, we check all figures before publication to try and identify potentially inappropriate image manipulation. Whenever we do come across a figure that doesn’t comply with our guidelines on image processing, we contact the authors to ask for clarification, request that the author provides us with the original data – so we can check that nothing fraudulent is going on – and often also ask that the final figure be changed to properly represent the original data. I’m happy to say that problems are few and far between, and that those issues I have come across in the short time I’ve been here have been more a case of beautification than of fraud. But is it okay for authors to ‘clean up’ their images with Photoshop paintbrush tools or the like: not touching the data itself, but rather getting rid of specks of dust or extraneous bits of tissue that are there on the slide?

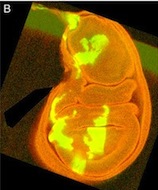

The images shown here don’t come from any paper, but have been kindly provided by a researcher to illustrate what I’m talking about.

This is a Drosophila wing disc, where clones of cells are marked with GFP, and the entire disc stained with phalloidin in red. Very often in preps like this, you get bits of irrelevant tissue associated with the disc on the slide. But this one looks very clean, right? Wrong. Here’s the original version – you can see that there’s a piece of trachea, stained red, off the left side of the wing disc.

So, thinking that this bit of extraneous tissue is problematic, the researchers have taken the simple solution of photoshopping it out: something that’s very clearly revealed by the standard checks we run on our figures: as shown here.

I’ve seen a seen a few of these cases recently, and in each, the aim of the authors was to ensure that the images were easily interpreted, and that readers weren’t diverted from the data by the extraneous bits of stuff. This may seem innocent, but it could be the first step on a dangerous slope, at the bottom of which lie the clearly fraudulent activities of deleting the bits of data that don’t fit our hypothesis, or making up data that do. Journal guidelines are (or at least should be) pretty unambiguous, and the case above falls foul of this statement taken from our Guide to Authors: “Unacceptable manipulations include the addition, alteration or removal of a particular feature of an image, and splicing of multiple images to suggest they represent a single field in a micrograph or gel.” So while it may seem innocuous, it’s not permitted. Nor is it, at least to my mind, in any way necessary: are we really that easily distracted? Does that little bit of trachea really stop us from seeing the clones in the wing disc? It’s been pointed out to me that the image above could have simply been re-cropped to remove the offending tissue, and if it’s okay to do that, why isn’t it okay to selectively black out those parts of the panel? That’s a reasonable point, and selective cropping is an issue to which I’m not convinced there is a straightforward answer. But I’m guided by the basic principle that the presented data should accurately reflect what you saw down the microscope or on the blot or whatever, and that what may seem irrelevant to you (a higher molecular weight ‘background’ band on your Western) might actually be important to someone else (“Oooh look – this might be a post-translational modification of my protein”).

I well remember from my time in the lab the agony of discovering that the perfect picture was ‘ruined’ by a bit of fluff to the side of the embryo, or because the vibrotome knife had left streaks across the section. And then spending hours re-mounting or re-sectioning to avoid these imperfections. But we all know that science can be an inherently messy endeavour: cells don’t grow in neat rows, and Western blots often give us background bands. So why do we need to hide this when it comes to publication? Of course, it’s vital that the data are clearly presented and understood, but what’s most important is that they accurately represent the experiment, and there’s a danger of losing sight of this in the desire for a beautiful image.

Initiatives like publishing all the uncropped blots that have gone into making the figures in a paper (as pioneered by Nature Cell Biology) are aimed at addressing this issue: by all means show only the relevant bit of the blot in the main figure, but for those interested in the (literally) bigger picture, the whole thing – warts and all – is available. But it can be a pain to find and assemble these files, and we don’t want to make publishing harder than it already is – although there’s a school of thought that says if you can’t lay your hands on the original data, you need to be better at archiving it in the first place!

So what do the Node readers think? Have you been tempted to ‘prettify’ your data for publication, or have you actually done it? Are our guidelines clear enough on what you can and can’t do? Do you support initiatives to make the raw data available to the reader, or is it all too much of a hassle? We’d really love your input on what kind of requests or demands a journal should make in terms of data presentation, so please answer the poll below (it’s completely anonymous!) and give us your feedback in the comments section.

Katherine Brown is the Executive Editor of Development

(4 votes)

(4 votes)

What’s the difference between the deliberately blackened out part and the 4 triangles of black created by cropping? Both show black in place of off-subject parts of the image. I’m not sure then how image C is any better than image B by the standard, “Unacceptable manipulations include the addition, alteration or removal of a particular feature of an image.” Perhaps close cropping should be allowed, but raw data should be provided in a supplement so that anyone can see the cropping?

You’re absolutely right and I did allude to this – there’s no real difference between selective cropping and the blacking out shown here. Except that, from a practical point of view, we can tell when someone’s deleted something within the field of view shown, but not necessarily when they’ve deleted something by cropping. Showing the raw data as supplementary material would be a great solution, but would you be willing to go to the all the hassle of assembling that file?

But then of course, you can go one step further: who’s to say that you didn’t set your field of view in the microscope selectively?!

I guess if this is the main kind of image manipulation we’re seeing, we’re on the lucky side: it’s very much beautification not fraud. But I’m struck by how much pressure people apparently feel they’re under to produce ‘beautiful’ images, rather than worrying mainly about scientific content. At Development, we’re proud of our reputation for beautiful figures and images, but if that creates a pressure that pushes people towards inappropriate data manipulation, then we should be worried…

While I agree that image manipulation is not an acceptable practice, the issue of cropping is a very challenging one. As to archiving raw data and making it available to others. I point you to The Cell: An Image Library-CCDB (http://www.cellimagelibrary.org). We accept submissions of images from the public, so why not start referencing entries in The Cell much as nucleic acid sequences were first referenced in GenBank. Put the pretty pictures in the Journals (not manipulated, but possibly cropped) but put all the image data in its raw form into the Cell for future analysis by others.

Thanks for the tip David: we’re actually looking into archiving resources at the moment, and while The Cell Image Library wouldn’t be appropriate for all our images, it might be a good place for certain data types. But would you be able to deal with the increase in volume if multiple journals started asking their authors to deposit raw data with you?

And this still doesn’t get round the ‘hassle factor’ of having to find and upload all this data! Perhaps I’m being unfair to authors, but I fear that many would find it frustrating if – at the point of acceptance – they were asked to go back and find all the original data to make it available for the community: as a Supplementary file with the journal or as archived data in your or other databases. You’re right – we routinely demand this for sequences, microarray data and the like, but can or should we do the same for all other data types?

Katherine,

We would definitely be able to deal with the increase in volume. In fact, that is one of our goals, to be the central repository for microscopy imaging data.

As to the hassle factor, there are a couple of options. First, if the community moves towards the GenBank model, images would be deposited with The Cell prior to publication and receive an accession number. This accession number would be required by journals and images, (data) would be stored at The Cell and only illustrative imaging would be shown in the journals.

Another option is for images to be deposited with The Cell at the time of article submission (while everything is current for the researcher) and held during an embargo period and then released to the general public through The Cell.

I believe many of the funding agencies are looking to ensure that the research that they fund is made publicly available and open and we can serve that purpose at The Cell.

As to your last question – should we? – I think it is very shortsighted of the community to not think that techniques and technology will continue to develop and that the analysis of this image data will also develop further. By not storing and cataloging this data now we are missing a great opportunity. Just as evolutionary studies of proteins could not have occurred until we started to amass all that data in one database, who knows what opportunities we are missing by not amassing all this image data in one place.

Not sure if having everything in one spot will help to be honest. One always has to build on the honesty of other people in the community. Not sure if (one more) huge database will help.

I think one should just stay as critical as possible and demand additional experiment which are well controlled when something looks funny.