A workshop to enhance thinking about and communicating research – a planktonic perspective.

Posted by Elizabeth Williams, on 17 May 2024

Elizabeth A. Williams and Gemma Anderson-Tempini, University of Exeter.

As biologists we work regularly with images to collect, interpret and communicate our data, findings and ideas. These days, however, images are almost entirely digital, and it is becoming increasingly uncommon to incorporate manually drawn pictures or 3D hand-crafted models into research, either during experimental observations or to communicate findings. Accurate scientific illustration is an important skill to record anatomical detail during an organism’s life, and realistic drawing was the main working method for early naturalists and anatomists, but drawing and modelling can also be used as a way to develop new ways of thinking about topics and processes from a different perspective1,2. We set out to explore how hand-drawing and 3D modelling could allow researchers today to engage with their research from new perspectives in a collaborative workshop guided by artist Dr Gemma Anderson-Tempini.

On the afternoons of Wednesday December 13th and Thursday December 14th 2023, we held a drawing workshop to bring together participants across three different research groups – (1) the ‘Molecular Marine Systems’ group of Dr Elizabeth Williams in the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences at the University of Exeter, (2) the ‘Micromotility’ group of Dr Kirsty Wan from the Living Systems Institute (LSI) at the University of Exeter, and (3) the ‘Algal Microbiome and Ecophysiology’ group of Dr Katherine Helliwell at the Marine Biological Association (MBA), Plymouth. Although focused on different research questions from different perspectives, the groups share an overlapping interest in understanding how microscopic organisms can sense, respond to, and move through their fluid environment.

Welcome to the workshop. We looked at planktonic larvae and discussed the potential of drawing: to infer or ‘draw hypotheses’, to ‘be like’ a biological process, to select salient information, to show and share understanding, and to constructively collaborate towards a processual view (Photo – Kirsty Wan).

Study organisms across the research groups include marine invertebrate larvae, microalgae, particularly diatoms, and protists. How these organisms transition between distinct phases of their life cycle in response to specific environmental cues is also of common interest across the different groups. We took inspiration from Maria Sibylla Merian, an entomologist, naturalist and illustrator (1647-1717) who was among the first to depict animal life cycles in the context of their specific environments at each different life phase3.

All research group members were invited to participate in the workshop and participants included group leaders, postdoctoral research fellows, graduate students and research technicians. Prior experience with drawing or art ranged from absolute beginner to confident regular practitioner. Workshop participants included scientists from both biology and mathematics backgrounds.

The first day of the workshop started with brief roundtable introductions and an overview of research topics by Liz and the practice of using drawing to represent dynamic biological processes by Gemma. As a drawing ‘warm-up’, we started with a group exercise on the ‘evolution of shape’, based on the drawing process developed by Gemma as part of her previous ‘Isomorphogenesis’ project, a drawing-based enquiry into the shared forms of animal, mineral and vegetable morphologies2.

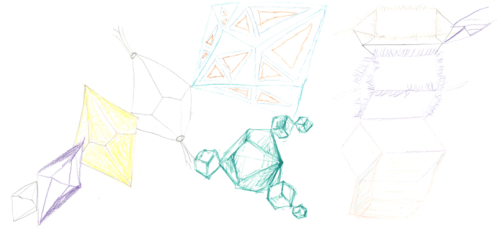

Each participant was given a 3D object to make an observational drawing. This drawing was then passed to the next participant, who added a connected object with an alteration suggested by selecting an action word at random. We continued the process until everyone’s initial drawing was returned to them, and observed the evolution of our original shapes. This allowed everyone to start drawing without feeling inhibited by the need to draw something perfectly, or the lack of an idea about what to draw.

Examples from the ‘evolution of shape’ group drawing exercise. A trend emerged across the group in that various forms started to accumulate cilia.

After this exercise, each participant was asked to draw a depiction of their own current research project or scientific question, and explain what it is they wanted their drawing to show. Examples of topics discussed included trying to understand how a microscopic organism could coordinate multiple cilia for effective swimming, or finding a new way to depict an organism’s life cycle by using continuous line drawing to highlight the connectivity between different life phases and promote the idea of considering an organism as its whole life cycle.

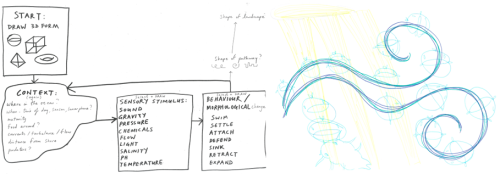

To conclude the first day of the workshop, participants were then asked to complete a drawing exercise similar to the initial ‘evolution of shape’, in which we imagined our organism of interest as a 3D shape, using questions to guide and direct the drawing: ‘What developmental stage is your organism?’, ‘What kind of environment is your organism in?’, ‘What type of response does your organism show?’. These questions also related to our prior recommended reading on the experience of larvae in flow4. In this exercise participants were encouraged to generate a bold drawing that would take up all the space available on their A3 blank sheet.

The instructions for the final drawing exercise on Day 1 (left), with an example outcome drawing of ‘worm larva movement in light and flow’ demonstrating an attempt to fill all the space on the page (right).

We started the second afternoon of the workshop with a short visualization exercise followed by discussion, to help bring participants into the present, and focus on their research questions. Participants lay or sat in comfortable positions with their eyes closed while Gemma guided them on a journey in the plankton as a microscopic organism, slowly dropping down deeper and deeper into the sea in search of a place to settle down on the sea floor. The effect of this exercise on participants was fascinatingly variable, with responses ranging from finding the experience stressful, busy and complicated, with many organisms jostling for position in the plankton, and the added complications of moving in a big 3D space, with different types of flow that could take an organism anywhere, and the ever-present threat of predators from every side. Other participants found the experience relaxing, due the perceived reduction in the types of decisions and actions they could take as a microscopic member of the plankton – sink or swim? The overall effect was to bring the group closer together and focused on the shared topic of marine microorganisms’ development and navigation.

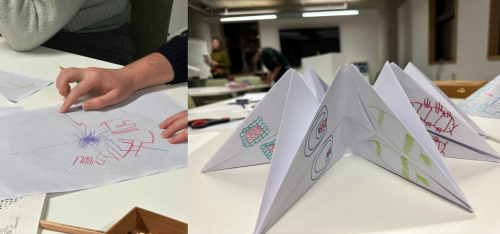

Following the visualization exercise, participants were offered a choice of activities including free-drawing with or without tracing paper, a paper folding origami activity, or the use of a circular maze template that could be converted from 2D circle into a 3D cone. These activities provided a basis from which participants could develop their own ideas about their research project or question. Examples of projects included using transparent layers to add information about environment and different life stage priorities to a coral life cycle, mapping the settlement journey of planktonic larvae through a circular maze, using the maze to demonstrate the carbon capture process during diatom sinking, or to develop an anatomical map of cell types in a marine larva. Origami structures were used to explore the life cycle of a marine worm, incorporating research goals into different sections, to explore environmental effects on marine larvae with changeable combinations of environmental factors, or to demonstrate biodiversity and morphology of diatom species.

Mapping the planktonic journey of larvae using a maze template (left), and developing an interactive marine invertebrate life cycle in 3D with origami (right).

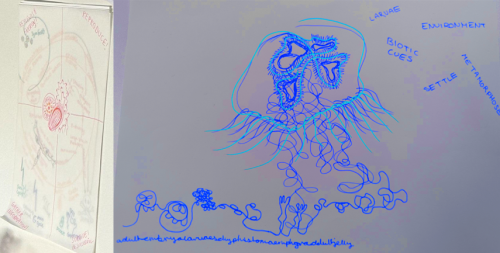

Following the independent work, we ended the second day with presentations and discussion of each participant’s work in progress. Consensus across the group was that drawing provided a useful way of thinking about research. There was strong interest in finding ways to incorporate drawing more into our research papers or use it as a tool to start thinking about and discussing new projects by drawing what the results could look like, the experimental plan, or the overarching question. This workshop showed us that drawing can be used to stimulate discussion, think about research projects, generate new ideas, images and hypotheses/questions, promote lab group interactions and understanding and collaboration between different research communities. Common themes that emerged from our discussions were the usefulness of drawing and paper craft as a tool for teaching and communicating, and to remind us of the bigger picture and broader impacts of our research.

Overall, it was useful to have some templates designed by Gemma to work with, such as mazes, games, or origami structures, which helped those unfamiliar with creative work or processual drawing, as these provided an initial framework from which to develop ideas. Representing biological phenomena such as metamorphosis, behaviour and movement as a process is not easy, but through the workshop interesting ideas emerged regarding both ways to represent a process dynamically, as well as ways to think about the process itself. For example, one participant developed a carousel model or zoetrope with which to demonstrate marine larval behaviours in response to changes in oceanic pressure, while another developed a diatom ‘teaching wardrobe’ with interchangeable layers allowing the demonstration of a diatom’s response to different environmental conditions.

Planning a zoetrope to demonstrate planktonic larval behavioural responses in action (left), and development of a ‘teaching wardrobe’ to demonstrate environmental effects on diatoms (right).

New ways of thinking about life cycles also emerged, in particular the representation of a life cycle as a spiral instead of the classic circle. This idea has an interesting synergism with the recent reflections by Sarah and Scott Gilbert on the prevalence of spiral forms in nature, and the possibility of thinking about the animal holobiont as two interlocking spirals, one representing the microbiome and the other the animal – ‘Circles are complete and perfect; life isn’t. Mathematically, the circle is merely the bounded collapse of the spiral. It is complete, but life goes on’5.

Developing new ways to think about coral (left) and jellyfish (right, digitally inverted for clarity) life cycles, with use of layering, spiral shapes or continuous line drawings.

A final take-away from the workshop was that the process of drawing and expressing ideas with paper crafts also allowed participants to incorporate their own identities and personalities into their work. We generated a space for participants to step away from the regular routine of lab work, experiments and computational data analysis, and take the time to think more deeply about their research questions. Participants were encouraged to leave phones and social media behind, although we allowed their use to access relevant images and videos online, promoting a focused atmosphere throughout the workshop. Slowing down, reflecting and sharing imaginative time with colleagues through drawing, creating and discussion, has strong potential to lead to new insights into scientific questions. Workshops such as this could be one tool to help researchers actively engage with the often microscopic life they are studying, enabling a process-oriented approach to ‘flow, attend and flex’, as recently proposed by James Wakefield6. We recommend this style of workshop to other scientists searching for artistic ways of thinking about and communicating their work.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the University of Exeter Living Systems Institute, for allowing us to host the workshop in their boardroom space, which was an ideal light-filled environment. This workshop was funded as part of a BBSRC David Phillips Fellowship (BB/T00990X/1) to Elizabeth Williams. We also thank each workshop participant for their valued contribution to this collaborative drawing workshop, which was in itself an experiment. Additional thanks to Dr Luis Bezares Calderón for helpful comments on the text.

References

- Anderson, G. 2014. Endangered: A study of morphological drawing in zoological taxonomy. Leonardo 47(3): 232 – 240.

- Anderson-Tempini, G., 2017. Drawing as a Way of Knowing in Art and Science. Intellect Books.

- Merian, M.S., Brafman, D. and Schrader, S., 2008. Insects & flowers: the art of Maria Sibylla Merian. Getty Publications.

- Hodin, J., Ferner, M.C., Heyland, A., Gaylord, B., Carrier, T.J. and Reitzel, A.M., 2018. I feel that! Fluid dynamics and sensory aspects of larval settlement across scales. Evolutionary ecology of marine invertebrate larvae, 13, pp.190-207.

- Gilbert, S.R. and Gilbert, S.F., 2023. “Process Epistemologies for the Careful Interplay of Art and Biology: An Afterword”, in Anderson-Tempini, G. and Dupré, J., 2023. Drawing Processes of Life: Molecules, Cells, Organisms, pg. 295.

- Wakefield, James G. 2023. “Flow, Attend, Flex: Introducing a Process-Oriented Approach to Live Cell Biological Research”, in Anderson-Tempini, G. and Dupré, J., 2023. Drawing Processes of Life: Molecules, Cells, Organisms, pg. 280.

(1 votes)

(1 votes)