An interview with Victoria Deneke

Posted by the Node, on 17 January 2023

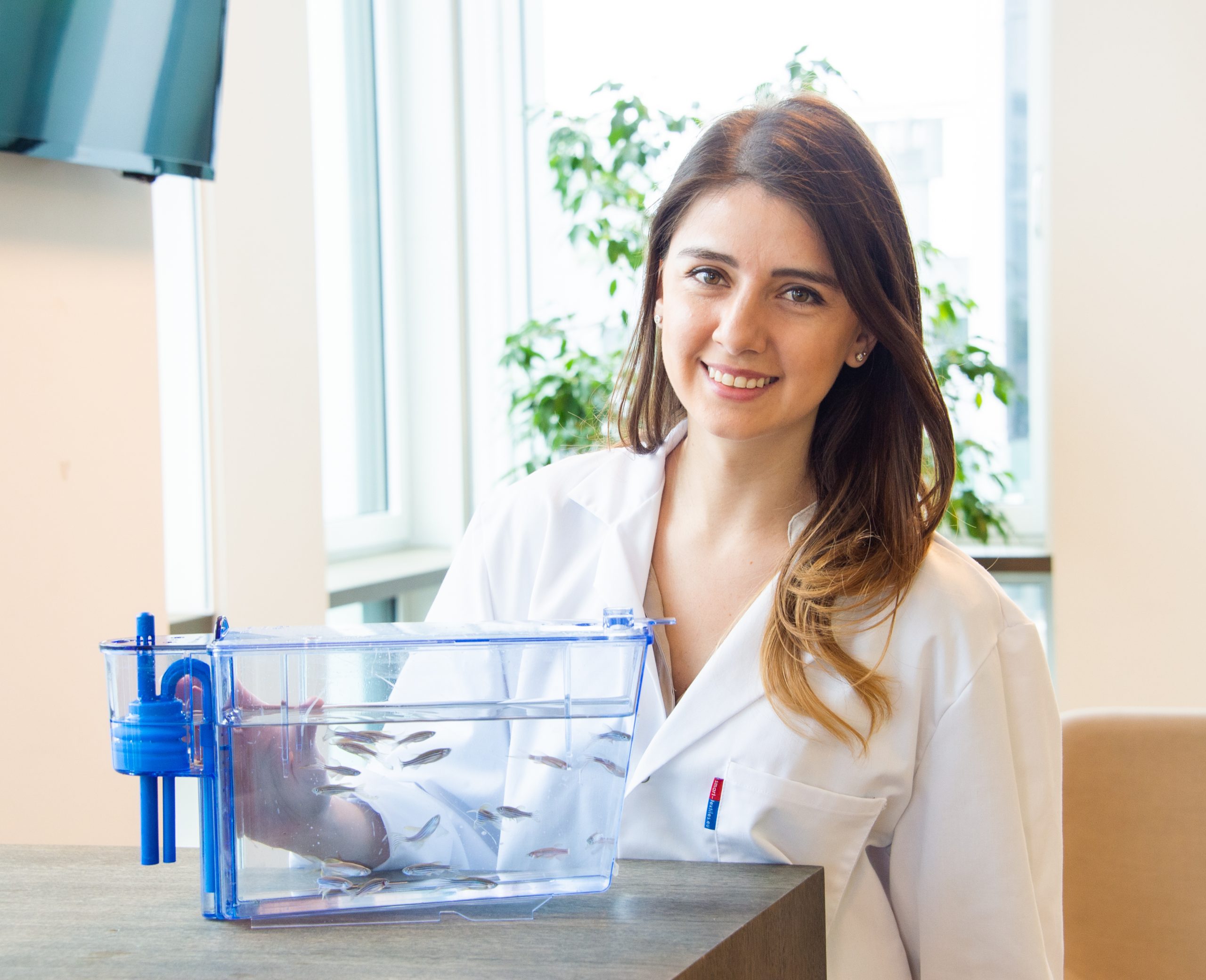

Victoria Deneke, a postdoc in Andi Pauli’s lab at the Vienna BioCenter, was the winner of the 2022 Society of Developmental Biology (SDB) Trainee Science Communication Award. Victoria is passionate about developing communities within the science world and creating opportunities for scientists from low-income countries. We caught up with Victoria to find out about her outreach and communication work, as well as her research career.

Where are you originally from and when did you first get interested in science?

I was born and raised in San Salvador, the capital city of El Salvador in Central America. Whilst growing, I was lucky enough to have access to school, and received a very good education. When I was 18, I applied for university places in the United States and that was when I really picked up science academically, but I’ve always been interested in the natural world. For example, I remember being fascinated by snake scales as a child and one of my favourite experiments in middle school was to dissect a frog to study the vasculature and the amazing organisation of the organism. Despite this early interest in biology, I decided to study chemical engineering as an undergraduate, as I thought that degree would be more versatile, either allowing me to return to my home country, or to develop elsewhere. Biology is not a very developed topic in El Salvador, but after my undergraduate degree I found myself being drawn back to biology. I decided to apply for umbrella PhD programmes, which give you access to a broad range of biology departments. You do rotations in different laboratories and then choose one for your PhD. This was an important aspect of the programme for me, particularly as I didn’t have a strong background in biology as an undergraduate. That’s how I ended up joining Stefano Di Talia’s lab, which was my fourth laboratory rotation. I very quickly fell in love with the research that was ongoing at the lab, which had just started at Duke. I was one of the first two graduate students that joined and the first graduate student that joined a fruit fly project. During my rotation, I was imaging early Drosophila embryos, and in particular the nuclear divisions that occur in the first few hours of development. These events are remarkably synchronous, and the waves of division spread through the embryo. My first PhD project was trying to figure out how these divisions are synchronised in the syncytial embryo. We found that there are waves of chemical activity via cyclin dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1), and through a combination of diffusion and positive feedback, these waves can synchronise the whole cytoplasm within minutes. It was the perfect project for me because it was very visual – I got to see and make these beautiful movies every day of my PhD! At the same time, the project involved not only biological concepts, like kinases and cell cycle regulation, but also concepts from physics and maths. For example, how the signal spreads, and the dynamics and the kinetics of chemical waves. This meant I got to collaborate with physicists, and indeed Stefano is a physicist by training, so I felt this project really suited my engineering background.

You said this was your first PhD project, can you tell us what you worked on for the rest of your PhD?

For the second half of my PhD, I decided to look at the role of cytoplasmic flows in spreading nuclei in the Drosophila embryo. So, originally these nuclei are all clustered in one part of the embryo and then there are beautiful contractions and subsequent flows that emerge and appear to move the nuclei. The regulation of the contractions is fascinating, and we assumed they must be tightly regulated for the nuclei to become so uniformly spaced through self-organisation. I started out by making movies of both the nuclei and the flows, trying to correlate these two movements. I went on to use optogenetics to perturb the contractions and monitor how that affects the nuclear spreading. Another beautiful, visual project where we really benefited from the application of quantitative biology methods. We tracked the cytoplasm and the nuclei and established quantitative relationships between these two movements to build a model. From the model, we made predictions that we then tested experimentally. I loved both of these projects, they allowed me to combine both imaging techniques and mathematical modelling, to address questions about fundamental developmental processes. Overall, I couldn’t have picked a better place for my PhD given my background and the kind of biology that excites me.

For your postdoc, you moved to Andi Pauli’s lab in Vienna, Austria, can you tell us about this move and your research in the Pauli lab?

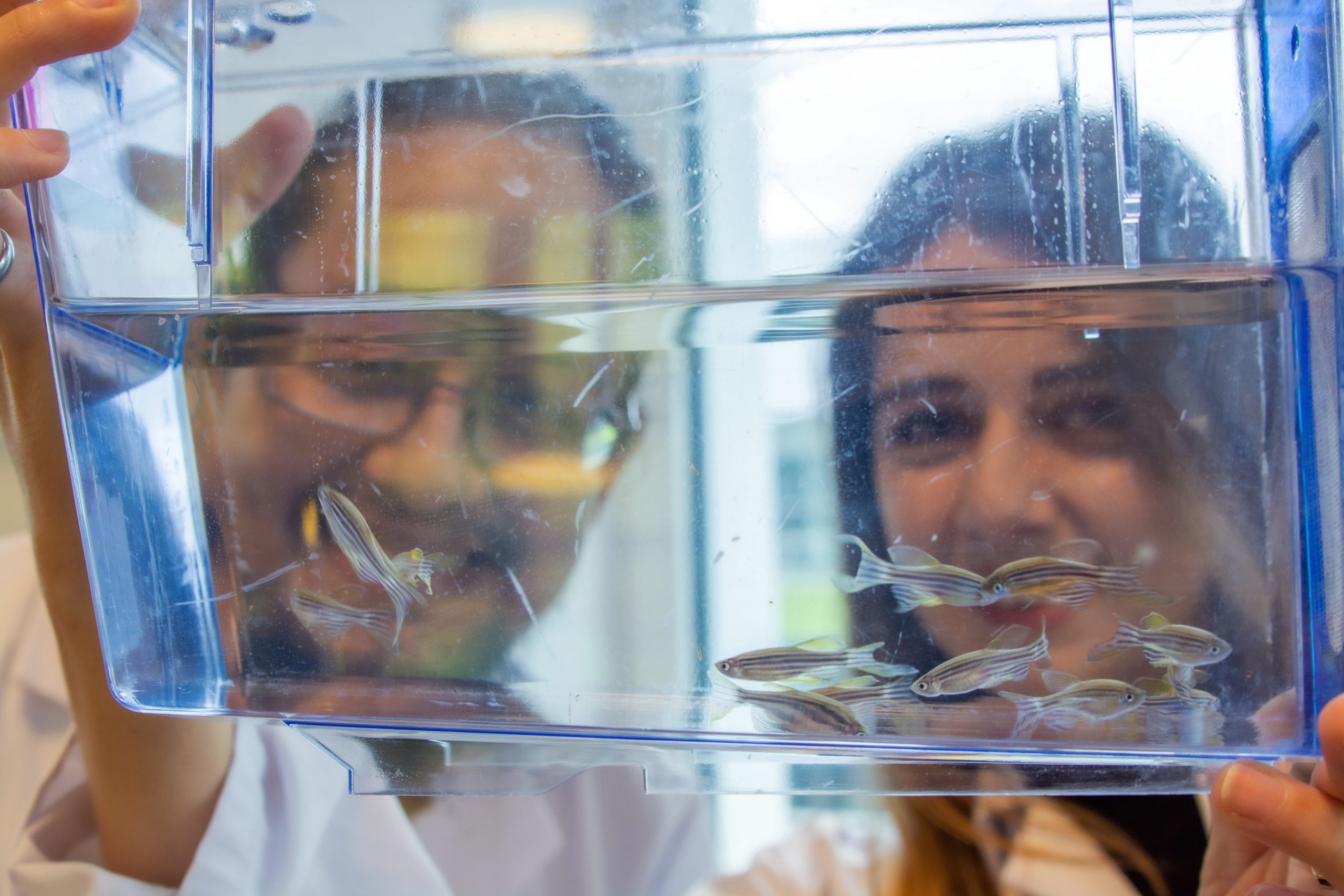

In the final year of my PhD, I started reading more broadly to find other scientific topics that interest me, and I always seemed to be coming back to oocyte and sperm biology. I’ve always thought that those cells are really fascinating and really special, and I was particularly drawn to the process of fertilisation, whereby these two cells have to bind specifically to each other and then fuse. I came across the first paper from Andi Pauli’s lab describing the discovery of a protein called Bouncer, which is on the surface of zebrafish eggs, and is an essential fertilisation factor. The other really cool thing that the Pauli lab found was that if you replace the zebrafish Bouncer with the medaka homologue, you can now fertilise the zebrafish eggs with medaka sperm, changing the compatibility of sperm and egg by just switching this one protein on the surface of the eggs. I thought this was amazing, so I reached out to her, keen to come for a visit. I was excited by the science and felt a good connection with Andi, so I decided to take a plunge and change completely scientific field, change model organism, change continents! It was quite a 180-degree change. I have been here for three years now, and I’ve really had such a good time. I think that picking an area of science that you’re just completely fascinated by for your postdoc is definitely the way to go. I don’t think I’ve ever had a day where I’m bored by my projects, I’m always wondering, what is really going on? How could we figure this out? So, I have been studying the process of fertilisation, mostly using zebrafish, and specifically I’m working on trying to decipher, which proteins, at the molecular level, are mediating this process, both on the sperm side and on the egg side. I love thinking about how these two cells come together and how they can achieve specific cell fusion between them. That’s a concept that really fascinates me and is my research interest in a nutshell!

Did you find switching model organisms a big change, or was that quite easy to do?

It was easier than I expected. I think it helped that the lab here (in Vienna) was already established and there were a lot of people in the lab that helped me pick up the zebrafish model organism. One of the biggest advantages of working with zebrafish is that the embryos are transparent. This means that you can look through a bright field microscope and watch development unfold. You can watch the embryo gastrulating and you can see even the somites forming, which was so exciting to me.

Congratulations on being awarded the 2022 SDB Trainee Science Communication Award, can you tell us what winning this award means to you?

This award means so much to me. I think oftentimes, this kind of work is considered extracurricular, and is overlooked. It’s wonderful that the SDB is recognising that outreach and communication are important aspects of academic science, and I think it shows the direction that we’re moving in. I think that being a well-rounded scientist is not just about making exciting discoveries in biology, but also about mentoring the next generation of scientists, and building an inclusive space for everyone. My short story of how I got involved into outreach work was when, after being in the US for a few years, I realised that I was in a unique position to contribute to my home country of El Salvador. I started doing simple outreach activities whenever I was back in El Salvador in the summertime. I would reach out to a local university and got involved with a workshop encouraging middle school girls to consider STEM fields. I would volunteer to give one of the Saturday morning workshops they do as part of a 12-week programme. One year I organised a workshop on pulleys. I borrowed some material from my high school and we ran this workshop together. So, that’s how it started and then eventually, as I got more involved with the Salvadoran community, I started reaching out to universities to also give motivational talks, to share my story. Then the next step was the fellowship that I created with my postdoc advisor Andi. But as you can hopefully see, the projects started very small, but through the years I built bigger and bigger initiatives.

Can you tell us a little more about the Austria-El Salvador Research Fellowship that you founded?

The idea originated from a yearly mentoring meeting I was having with Andi. We were talking about the Vienna BioCenter Summer School, which is open for students from all over the world to apply to come for a summer research internship at the Vienna BioCenter. It’s an amazing programme, but the realities are that students from lower income countries do not have access to the same opportunities as applicants from other parts of the world. This means that they usually don’t make the cut for the normal programme that we run here. I suggested to Andi that we could try to fill this gap by inviting one person for the summer, see how it goes and take it from there. Since I am very connected to the community in El Salvador, it was easy for me to broadcast the application within El Salvador and then find a student who would be motivated to come join us for a summer. We extended an offer to a student called Eduardo. He was here for three months and I was his direct supervisor. One thing that really stood out was that he was always so eager to come to the lab, and so grateful and amazed by the facilities. He loved the library and would go in the evenings to read books, access that we take for granted. It was really fascinating and inspiring for me as a mentor and made me really start appreciating the resources that we have here. Even though he had never had any research experience, he quickly picked up a lot of concepts. Eduardo is a very talented scientist, and it was a treat to mentor him. I also became aware of a lot of barriers within developing countries that kind of inhibit the progression of science. I’ve heard a lot of stories of having to use makeshift reagents and delayed services to developing countries, which means that science moves a lot slower because you just don’t have access to the same resources. For Eduardo, the fellowship was his first research experience, his first opportunity to try out the techniques he had read about, and it allowed him to be immersed in science. He has also taken his knowledge back to El Salvador. He has started a molecular biology club within his university, where they read papers together and they are creating a scientific community of students back home. It’s a small thing, starting with just one person, but I think in the long run it could really have an impact in how biology develops in in low-income countries, and in El Salvador, in particular.

The bulk of the funding for the fellowship was from the Vienna BioCenter, but I also made a GoFundMe page to have additional funds to use to cover Eduardo’s travel, as well as a small stipend to cover living costs during the three months. I think it is important to remember that if we’re going to bring someone from a low-income country, you cannot expect that that person will be able to cover a roundtrip flight from across the world. We really wanted to be as accommodating as we could and consider the reality of the applicant, including funding travel, visa, but also being aware of access to opportunities when considering the strength of the application. As we move forward in creating an inclusive scientific environment, we have to consider, are we missing out on talent because of barriers to access these kinds of opportunities?

I saw that you also ran a do-it-yourself workshop for teachers in El Salvador, how did this course work and did you intentionally target teachers rather than students?

The do-it-yourself microscopes is a workshop that was developed by Bob Goldstein at UNC Chapel Hill. The premise of his programme was to offer this workshop to teachers, in his case in North Carolina. I came across Bob’s work in a conference where he had a stand with these microscopes. I talked to him about the idea of bringing this workshop to a low-income or an underprivileged country. I thought it would be a perfect fit to introduce both teachers and students to science because it was very affordable, the microscopes are easy to make, but nonetheless, give you access to the microscopic world. I think that all of those factors make it a perfect outreach tool for low-income countries. I saw the value in Bob’s programme to target teachers so that they could expand their knowledge and amplify that effect to their students, so we decided to implement this programme in El Salvador in a very similar fashion. I translated all the material, but Bob has this ‘Ikea-like’ drawing of how to build this microscope, so you don’t need a lot of text. I was also lucky to partner with a local university and we recruited around 40 to 50 teachers from across the country. It was such a good workshop; everyone came out so happy and so proud that they built this microscope. It was fun watching people’s first reaction, when they put say a leaf under this microscope, and all of a sudden, they could see the cells. A lot of these teachers had never seen that, not even in a textbook. The teachers wanted to take the microscopes into to the classroom, but they also wanted to show their families because they were so excited by it!

How can we, as a community, better support and promote scientists from low- and middle-income countries?

We’ve touched on some aspects already, and I think that we are in a very unique position to be able to provide opportunities to students from disadvantaged backgrounds. As a community, we should support open calls, specifically to recruit people from low-income countries, or we could reserve spots within our existing programmes to include talent from disadvantaged backgrounds. And we need to think about the barriers could prevent people from participating in such programmes. The exercise of putting yourself in other people’s shoes could really transform the way that we run a lot of our research programmes and we are currently discussing how we could implement this here at the Vienna BioCenter. We are discussing how, within our current summer programme, we can reserve spots for students from low-income countries, and what would we need to provide to really support the students participating in the programme.

It’s exciting to think that something can start with a small project, inviting one person into the lab, but then if that could be amplified to say 20% of institutes offering a few weeks in the lab, there would be a huge number of scientists benefiting from this kind of experience.

Yes, that’s a really good way of thinking about it. It could be applied to any research institute across the world and could really have an impact. But I think it is good to start with a small ‘experiment’ and then really pitch for implementing something bigger. That’s my hope. I hope that for next summer we can already reserve ~20% of the spots on our research programme for students from underprivileged backgrounds with the idea that we recognise that talent is everywhere, and that science also benefits from a diverse talent pool. And so, in that effort, we have restructured the programme to allow for this enrichment.

You’ve spoken about Andi Pauli and Bob Goldstein as mentors. Do you have any mentors or role models either in research or science communication and outreach?

One person that comes to mind was someone that I intersected with during my time at Duke. I was really lucky to be part of this programme called the Biocore Scholars programme, and this programme is led by an amazing scientist, advocate, and communicator, Sherilynn Black. Sherilynn created this graduate student programme that’s designed to build a supportive community for PhD students of diverse backgrounds. I applied to be part of this programme and remained in the programme throughout my PhD. It became my scientific home during my PhD. It was a cohort of really diverse students that were in the programme to come together and support each other and collectively move through our PhD experiences. I really owe my PhD to this community. It has made me passionate about community building within scientific spaces that allow people to thrive. If I could be a fraction of Sherilynn Black, I will have made it in life!

What’s next for you, both short term and longer term?

In the short term, I’m really enjoying my postdoc here at the Pauli lab. I love mentoring students and I think that the scientific world is the perfect ground for building communities, for mentoring people and for coming together and communicating our science broadly. In the long term, it’s hard to say, but I would be looking for something that allows me to continue this role of creating community, communicating science, and mentoring students. I think that my future role could take shape in many ways for me.

Where do you think developmental biology will be in ten years?

During my PhD, I was introduced to the field of quantitative biology and the additional insights that quantitative methods can provide into the dynamics and the regulation of biological processes within developing organisms. I’m curious to see how this field is going to keep evolving. And not only that, but how interdisciplinary projects that use concepts from physics or concepts from computer science, can bring new insights to biological questions that have been studied for a long, long time. At the SDB meeting, for example, we started seeing how people are using AI to be able to predict differentiation cascades – I think that that is truly fascinating. And combining that with detailed data sets of transcriptional states of cells can really propel the developmental biology field forward. So, those are the things that I’m really excited about, but whether that actually ends up being the crux of developmental biology in 10 years, who knows, but that’s something that I look forward to reading about!

When you’re not in the lab, what do you do for fun?

I really love going on walks. I have a sister that lives with me here in Vienna and every weekend we pick a different district or a different neighbourhood in Vienna to walk around. I think it is a great way to know a city. I also love travelling, and one of the biggest advantages of being in Central Europe is that I have access to a lot of beautiful cities, just amazing historical places. When I travel, I enjoy getting to know the culture and the food of different countries. Those are two of my big ones, but I also really enjoyed dancing, so that’s something I like to do on the weekend.

(1 votes)

(1 votes)