BSDB Gurdon Summer Studentship Report – Delia Capatina

Posted by Delia Capatina, on 28 November 2022

Investigating the rules of cell-to-cell interaction during pre-somitic mesoderm elongation

I discovered the field of developmental biology through independent reading during the first year of my undergraduate biomedical sciences program. I was fascinated by the process through which embryos develop, and the more I learned, the more questions I had. As Lewis Wolpert said, “Understanding the process of development in no way removes that sense of wonder”. I knew I wanted to gain some experience in working with embryos and I had the amazing opportunity to work in Ben Steventon’s lab at the Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge.

During development, cells interact with one another to generate collective migration. For example, cranial neural crest cells counterbalance contact inhibition of locomotion and coattraction to migrate through the embryo (Carmona-Fontaine et al., 2009; Carmona-Fontaine et al., 2011). The interactions between the cells of the pre-somitic mesoderm during vertebrate elongation are not understood as well. I focused on investigating the behaviour of the medial somite progenitor (MSP) population, using chick embryos as a model system.

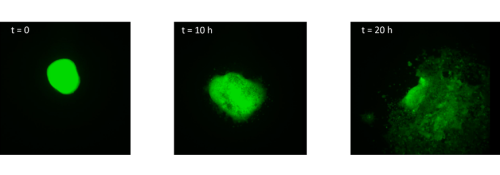

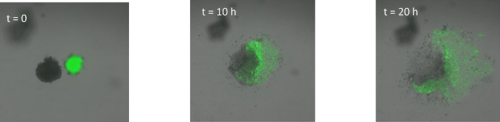

I started by taking stage HH4 chick embryos out of eggs and placing them in PBS. Using a small syringe needle I then explanted the MSP region, which is located in the anterior primitive streak just below Hensen’s node. I transferred each explant on a dish coated with fibronectin and I imaged them every 10 minutes for 20 hours. After watching how the cells migrate in the dish (figure 1, movie 1), I wanted to find out how different explants would interact. I decided to culture two explants from the same region (anterior streak) next to each other, as well as an explant from the anterior region and an explant from the posterior region.

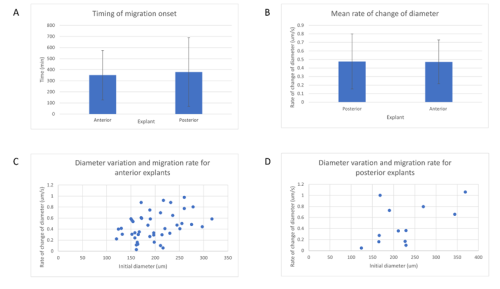

Surprisingly, in both situations, the cells did not mix. The anterior streak explants attracted each other in some cases (figure 2, movie 2), while the posterior streak explant seemed to be attracted by the anterior streak explant (figure 3, movie 3). There is no significant difference between the average timing of migration onset in anterior and posterior explants (figure 4A). To measure the rate of migration, I calculated the rate of change of diameter, and again there was no significant difference between the two populations (figure 4B). The attraction is not likely to be influenced by the distance, as there is no significant difference between the mean initial distance separating the explants in the cases where attraction occurs or does not. However, there seems to be a weak positive correlation between the initial size of the explant with the rate of migration. Explants with a larger initial diameter generally have a greater rate of change of diameter. This is true for both anterior explants (figure 4C) and posterior explants (figure 4D).

A – Mean timing of migration onset in anterior and posterior streak explants. A T test was performed, and there is no significant difference between the onset of migration (p = 0.529).

B – Mean rate of change of diameter of posterior and anterior explants. A T test was performed, and there is no significant difference between the rate of change of diameter (p = 0.819).

C – Variation of the rate of change of diameter against initial diameter in anterior streak explants. There is a positive correlation between the initial diameter and the rate of change of diameter.

D – Variation of the rate of change of diameter against initial diameter in posterior streak explants. There is a positive correlation between the initial diameter and the rate of change of diameter.

I had an amazing experience working in the lab. Initially, I found it tricky to remove the embryos out of the egg and explant the region. I ended up breaking a few embryos and losing some explants. However, practicing the techniques every day helped me improve quickly. Each week I got more and more comfortable doing my experiments and my movies have significantly improved. The people in the lab were very friendly and always happy to help, so I had great support throughout my placement. I enjoyed the lab environment and the weeks passed by incredibly quickly. If I had more time, I would have liked to investigate the role of FGF signalling in the migration of these cells. I would have liked to inhibit FGF receptors to find whether the explants still attract or not, since streak cells are attracted by FGF4 and repelled by FGF8 (Yang et al., 2002). However, there seems to be more FGF8 and less FGF4 in the MSP region (Lawson et al., 2001; Shamim and Mason, 1999), so the fact that the explants attract seems to oppose this evidence.

I am interested in pursuing a PhD and my experience from this summer has only made me more determined. I gained valuable insights into the reality of working in research. I had encountered some difficulties with my experiments and spent some time troubleshooting, however that did not put me off. Moreover, it made the results so much more rewarding, giving me a realistic view of what it is like to start a new project and how long experiments take. I appreciate the freedom I had in deciding which experiments to perform, how I would analyse the data, and the general structure of my day.

I think everybody who is curious about research should apply for a BSDB summer studentship. There is nothing like experiencing research first-hand. I would like to thank Ben for hosting me in his lab, Tim for encouraging me to apply for this scheme in the first place, and everybody in the lab for teaching me various skills and being patient with me.

References

Carmona-Fontaine, C., Matthews, H., Kuriyama, S., Moreno, M., Dunn, G., Parsons, M., Stern, C. and Mayor, R., 2008. Contact inhibition of locomotion in vivo controls neural crest directional migration. Nature, 456(7224), pp.957-961.

Carmona-Fontaine, C., Theveneau, E., Tzekou, A., Tada, M., Woods, M., Page, K., Parsons, M., Lambris, J. and Mayor, R., 2011. Complement Fragment C3a Controls Mutual Cell Attraction during Collective Cell Migration. Developmental Cell, 21(6), pp.1026- 1037.

Lawson, A., Colas, J. and Schoenwolf, G., 2001. Classification scheme for genes expressed during formation and progression of the avian primitive streak. The Anatomical Record, 262(2), pp.221-226.

Shamim, H. and Mason, I., 1999. Expression of Fgf4 during early development of the chick embryo. Mechanisms of Development, 85(1-2), pp.189-192.

Wolpert, L., 2008. The triumph of the embryo. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, p.199.

Yang, X., Dormann, D., Münsterberg, A. and Weijer, C., 2002. Cell Movement Patterns during Gastrulation in the Chick Are Controlled by Positive and Negative Chemotaxis Mediated by FGF4 and FGF8. Developmental Cell, 3(3), pp.425-437.

(5 votes)

(5 votes)