Engaging the public with fundamental biology: why it’s tough but still worth doing

Posted by Naomi Clements-Brod, on 22 March 2023

by Naomi Clements-Brod and Hélène Doerflinger

What is Public Engagement with Research?

Public Engagement with Research (PER) encompasses ways of engaging the public with the design, conduct and dissemination of research. Engagement is, by definition, a two-way process to generate mutual benefit for society and the research community by enhancing research quality and socio-economic impact (See the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement webpage for more information).

Engaging with the public can take many forms. The format is chosen according to the audience, the aim, the nature of the research and the capacity of the PER team. Examples of public engagement activities are:

- citizen science experiments

- panel discussions

- interactive exhibitions

- festival participation

- school collaborations

- co-creation with artists

- contributions to mainstream and social media

There is no hierarchy of engagement approaches. If meaningful and two-way, they are all valid in their own format, and very often, an event or an activity will contain a blend of these approaches and purposes.

The mutual benefit for society and the research community is essential to PER. Benefits might include learning, acquiring new skills, gaining new insights or ideas, developing better research, generating a new network, raising aspirations, or being inspired.

The ways scientists interact with the public across the world differ. Some countries continue with the ‘outreach’ approach, which is mainly a one-way communication to generate attention. In contrast, other countries develop citizen science programmes with multiple educational, social, and economic impacts.

So, we’ve established that public engagement in the UK is more than just educating the public about science – crucially, it is two-way, and involves finding out what the public think about our science too. But how did public engagement come to have this emphasis on two-way communication in the UK?

The story of genetically modified food

A big part (but not the only part) of this story started in the late 1990’s, when there was widespread scepticism and anxiety about genetically modified (GM) food. (Rowe et al., 2005). This public concern around GM food was not just about the science, either: press coverage at the time reveals it was also a political, environment and consumer issue (Durant & Lindsey, 2000).

In 1998, to ease public scepticism, the UK government decided that GM crops wouldn’t be grown commercially in the UK until a set of experiments on farms had been completed. However, this didn’t dampen public opposition: local communities were angry about not being consulted about these farm experiments in the first place (Mayer, 2003). Then, in 1999, major UK food producers and retailers responded to consumer pressure and removed GM ingredients from products on shelves (Mayer, 2003).

In the midst of the GM food controversy, Parliament also issued a report encouraging scientists to engage in dialogue with the public. They recommended openness and transparency in order to help regain public trust, placed greater emphasis on public attitudes, opinions and values and recognised that without public buy-in, science would struggle to move forward. (Science and Technology Select Committee, 2000).

In 2003, the government ran a series of public debates, in parallel with scientific and economic reviews of the issue of GM food. However, despite asking the public what they wanted, there was still widespread polarisation, opposition and scepticism (Mayer, 2003). And today, more than 20 years later, the legacy of anti-GM sentiment in the UK still lives on.

Lessons Learnt

So why didn’t this dialogue with the public work? One of the big reasons scholars give is that the public were involved much too late and it wasn’t clear how their input would be used in the decision-making process. As a result, engagement professionals today are keenly aware today that public engagement needs to be more than just window dressing: when science will impact people’s lives, scientists can’t just use ‘dialogue’ to try to legitimise a decision that has already been made. You have to ask people what their concerns are early enough so that you can respond to what they tell you in a meaningful way, ensuring that your research. and its potential outcomes. are aligned with societal priorities and expectations. (Mayer, 2003; Rowe et al., 2005; Singh, 2008; Marris, 2015; Morrison & de Saille, 2019; de Saille & Martin, 2018; Gjerris, 2008).

Another big take away from the GM story is that increasing public knowledge about biotechnology won’t necessarily mean that people agree with you about how and whether that biotechnology should be used. Disagreements can be fuelled by different interpretations of the facts, often reflecting individual and cultural values. While science can help us answer ‘can we’ questions, science can’t always directly answer ‘should we’ questions – this is why public input is so vital.

This history informs today’s aim to have two-way conversations with the public, regardless of how fundamental the research is, in order to ensure the ultimate outcomes of science are considered mutually beneficial.

Challenges of engaging with fundamental research

While mutual benefit sounds great, there are certainly some challenges to public engagement with fundamental research, when the research outcomes are often unknown. For example, engaging with the public about implications that are remote and uncertain can encourage ideology-based reactions, leading to polarisation and conflict (Tait, 2009; Tait, 2017).

And while today’s public engagement encourages dialogue over merely informing the public, when speaking with non-scientists about fundamental research, there is often a substantial need to build shared language and understanding of the topic before informed conversations can take place. Meaningful PE with fundamental research can take a lot of time and resources (Clements-Brod et al., 2022). However, it is not impossible!

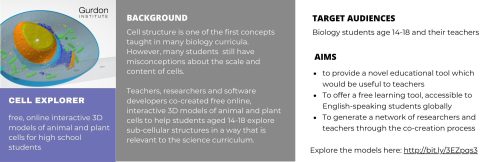

Case studies

We’ve put together some examples of how we’re doing public engagement with fundamental research in hope to inspire others to do the same.

References

Clements-Brod, N., Holmes, L., and Rawlins, E. (2022). Exploring the challenges and opportunities of public engagement with fundamental biology. Development. 149 (18) https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.201170

de Saille, S. and Martin, P. (2018). Monstrous regiment versus Monsters Inc.: Competing imaginaries of science and social order in responsible (research and) innovation. In Science and the Politics of Openness: Here be Monsters (ed. B. Nerlich, S. Harley, S. Raman and A. Smith), pp. 148-166. Manchester: Manchester University Press. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/30733 [accessed 11 August 2021].

Durant, J. and Lindsey, N. (2000). The ‘great GM food debate’ – a survey of media coverage in the first half of 1999. Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. Report number: 138 https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/post/report138.pdf

Gjerris, M (2008). The three teachings of biotechnology. In David, K.H. & Thompson, P.B. (eds.), What Can Nanotechnology Learn From Biotechnology?: Social and Ethical Lessons for Nanoscience From the Debate Over Agrifood Biotechnology and Gmos. Elsevier/Academic Press., pp. 91-105

Marris, C. (2015). The construction of imaginaries of the public as a threat to synthetic biology. Sci. Culture 24, 83-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2014.986320

Mayer, S. (2003) GM Nation? Engaging people in real debate? GeneWatch UK.

http://www.genewatch.org/uploads/f03c6d66a9b354535738483c1c3d49e4/GM_Nation_Report.pdf

Morrison, M. and de Saille, S. (2019). CRISPR in context: towards a socially responsible debate on embryo editing. Palgrave Communications 5, 110. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0319-5

Science and Technology Select Committee. (2000). Science and Society. House of Lords, Parliament. Report number: 3. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld199900/ldselect/ldsctech/38/3802.htm

Rowe, G., Horlick-Jones, T., Walls, J. and Pidgeon, N. (2005). Difficulties in evaluating public engagement initiatives: reflections on an evaluation of the UK GM Nation? Public debate about transgenic crops. Public Underst. Sci. 14, 331-352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662505056611

Singh, J. (2008). The UK Nanojury as ‘upstream’ public engagement. Participatory Learn. Action 58, 27-32. https://www.participatorymethods.org/resource/uk-nanojury-upstream-public-engagement[accessed 29 June 2021].

(1 votes)

(1 votes)