Publishing Fly Research

Posted by Katherine Brown, on 9 May 2019

Back in January, The Cambridge Fly Club held a symposium to mark 25 years since the publication of the famous Gal4/UAS paper (Brand & Perrimon, 1993 – published in Development); the organisers have posted a meeting report here. As part of this symposium, the organisers asked me to give a talk on ‘Publishing Fly Research’. Particularly given that I worked with Drosophila in Cambridge as a research assistant and PhD student and attended the odd Cambridge Fly Club talk back in the early 2000s, I was more than happy to oblige, though I wasn’t initially sure what I was going to talk about – surely publishing fly research is just like publishing any research?!

But I decided that I wouldn’t just trot out my ‘standard’ publishing talk, and that instead I’d try and take a look at the publishing landscape for the fly community, and at how it’s changed since the publication of that landmark paper. Some of the data I gathered surprised me, and given that the audience seemed to find my insights useful, I thought I’d (somewhat belatedly) share them here. I also hope that this post will be useful beyond just the fly community, though I’ve not crunched the numbers for other systems.

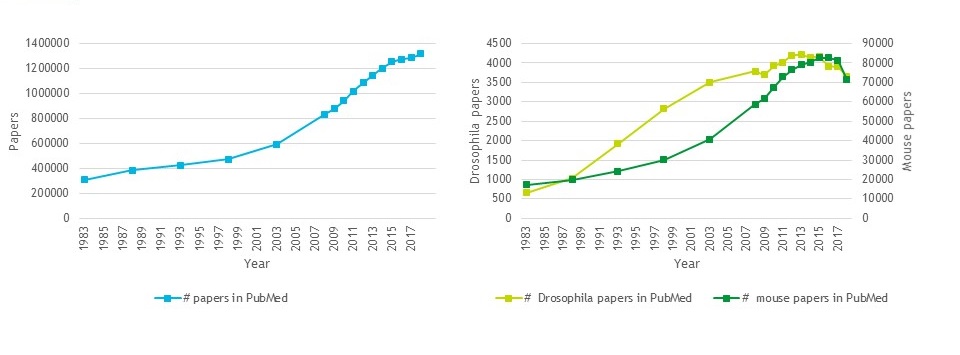

So, what I looked at was the number of fly papers published over recent decades, and where they were published, and compared this to the number of mouse papers (representing the most popular vertebrate model system) and total papers. I also looked at citation rates, as well as at submission rates to Development. An important caveat: my analyses are very crude, and are based on keyword searches in PubMed, Web of Science and Development’s own submission system. For certain there are both false positives and false negatives in the numbers, but hopefully the trends still hold.

Looking over the past 35 years, it’s clear that publishing output has increased dramatically, and fly research has more than kept pace with this, ramping up massively in the 90s before plateauing in recent years.

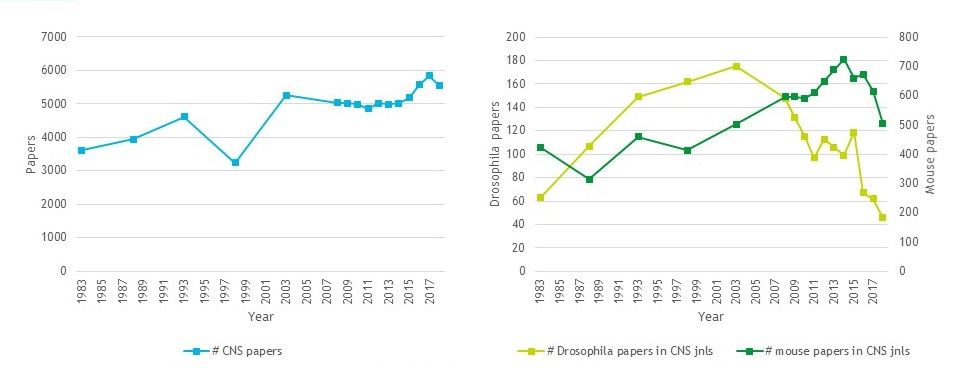

But what about the influence of the fly field? Using papers published in Cell, Science and Nature as a (very imperfect) proxy for how ‘hot’ a field is, you can see that we hit ‘peak fly’ in the early 2000s, and the numbers of fly papers published in those journals has declined since then.

Incidentally, we see a not dissimilar trend in Development. So where are fly papers being published? Back in 1993, the top venues for Drosophila research were Development, PNAS and Genetics. In 2018, it was eLife, Scientific Reports and PLoS Genetics; the most popular journals in the early 90s still make the top 10, but have been pushed down the pecking order primarily by large, broad scope OA journals (PLoS One and Nature Communications completed the top 5 in 2018).

It’s also the case that fly papers aren’t as well cited as mouse papers. I didn’t have access to historic citation data, but for publications in 2015, the average fly paper in the CNS journals cited half as well as the average mouse paper. The differences aren’t this dramatic for Development papers, but they are still there. And I think this is largely to be expected – the mouse community is larger than the fly community, so it’s natural that those papers will get more citations. Plus, I suspect a fly paper is much more likely to cite mouse work than the other way around – given the current ecosystem that values (perhaps overly values) mammalian and translational relevance.

So is it getting harder to publish fly papers? Looking at submission and acceptance rates in Development over the past 10 years, it seems that what has declined is submission rate – fly papers submitted to us are just as likely to be published as they were a decade ago, and they’ve got an above-average acceptance rate.

We just don’t see as many papers submitted to us as we used to (2017 submission rate was 60% that of a decade earlier). Whether this reflects changing journal preferences of authors, or a decline in the volume of Drosophila developmental biology papers, I can’t say. But I think it’s fair to argue that fly work doesn’t have an overly hard time with us.

I was also asked to comment in my talk on how fly researchers can maximise their chances of getting their work published and seen by a broad audience. It’s important to state from the outset that – at Development at least – fly papers are treated just the same as any paper: what we’re looking for are studies that advance our understanding of developmental processes, or report techniques or resources of broad interest to our community. We don’t need translational relevance and we don’t need you to replicate or confirm your findings in another system. But we are looking for papers that we think will be of interest beyond a small group of researchers in a particular area, and it’s helpful if you as authors can make it clear where that interest lies. This is important not only to get your paper past the editor and referees, but also to make sure it gets read once it’s published. Remember that the vast majority of people who come across your paper will only read the title. A small proportion might click through to see the abstract, and even fewer will go on to read the full paper. So, while I’m never going to advocate overselling a paper, it will help to make clear the broader context up-front, and make the title and abstract appealing to non-fly people. Avoid fly-specific jargon and gene names (refer to E-cadherin, not shotgun!), and help the non-aficionados to realise the potential link to their own work.

Concrete examples are often more helpful than generic advice. So, and to avoid embarrassing anyone but myself, I went back and looked at my own very first paper – which I’m proud to say was published in Development. But looking at it now, the title and abstract fail to follow most of the advice given above. Just before my talk, I had a quick go at pulling the abstract apart and rewriting with my editor hat on. My new version is far from perfect, but hopefully it serves to exemplify the points I’ve made – scroll through the images below to see the first version, its flaws revealed, and a few little rewrites that at least start to make it more accessible. The title isn’t great either in terms of accessibility, though I remember Matthew and I agonised over the wording. If I had the chance again, I’d go with a simpler version – something like “Egfr signalling regulates ommatidial orientation in the Drosophila eye”. I fear the word ‘ommatidial’ would put most readers off immediately, but it’s hard to avoid – suggestions in the comments please!

(4 votes)

(4 votes)