The Future of Research Symposium:

How Scientists are Trained

Posted by Gary McDowell, on 23 September 2014

This is the first of four posts relating to the Future of Research symposium which was announced in a previous blog post. Each of these posts will discuss a topic that is the focus of a workshop at the Symposium. Even if you can’t attend, please tweet @FORsymp with suggestions, or follow us to respond to our questions about what YOU, trainee scientists, think is important. The hashtag for this post on the Training workshop is: #FORtraining

Who is a “trainee”?

By training, we are referring to the period between obtaining an undergraduate degree getting a first faculty-level position: graduate students and postdocs.

At this point in time, the common thread to training consists of the accumulation of research experience, culminating first in a dissertation for defending a PhD thesis, and then to produce science (most directly in the form of publications) during postdoctoral research, designed to be a more independent research environment under the scope of a Principal Investigator. The goal is then for a trainee to be able to find an academic position, beginning their own lab.

How many trainees are there, and how has this changed over time?

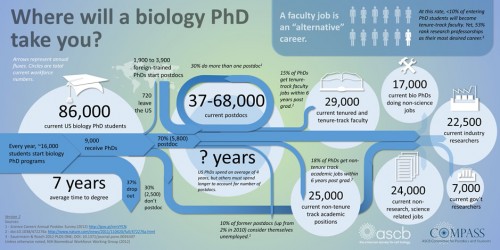

The NIH Biomedical Research Working Group Report (2012) makes for sobering reading. The proportion of PhDs moving into tenured or tenure-track positions decreased from 34 % in 1993 to 26 % in 2012, whilst the proportion of non-tenured faculty has remained constant but increasing in terms of actual numbers. The number of graduate students has doubled in the same time. Numbers of postdocs are harder to track, because nobody seems to, but estimates are that these numbers have also doubled (the NIH Biomedical Research Working Group Report implies that even this could be under-estimated by as much as a factor of 2). Research Training in the Biomedical, Behavioral, and Clinical Research Sciences, by the National Research Council (2011), suggests that as of 2011 there may have been just over 50,000 trainees in the biomedical research system.

How long is one a trainee?

In the US system, PhDs can take anywhere between 5 and 10 years. Postdoctoral training has been identified by the NIH as only being 5 years on average, but the number of people doing up to 8, or even 10 and beyond, has been steadily increasing in recent years. Some institutions put a cap on how long someone can be a postdoc, with a requirement to then make them a research associate.

What trainees expect, and where they end up

The assumption is that everyone who goes into academia wants to end up an academic. Is this the case? Expectations have been shown to change over time as a trainee, with a recent study showing that a faculty position tends to become less attractive over the course of a PhD, although by the end it is still the preferred career path for 50 % of trainees (Sauermann and Roach, 2012). This is in spite of strong encouragement from advisor, who actively discourage other career paths (Sauermann and Roach, 2012).

And the jobs people are actually getting (taken from Polka, 2014) show that, actually, academia is one of the “alternative” careers, and not the default. Less than 10 % of entering PhD students become tenure-track faculty: contrast this to the 50 % identified previously as having academia as their primary goal (Sauermann and Roach, 2012).

Taken from Polka, 2014

What are trainees supposed to accomplish?

This workshop is first going to discuss the question, “In what way are trainees unprepared?” and then depending on what attendees come up with, will then ask, “What are the solutions to these problems?” Then attends will try to arrange these according to feasibility/difficulty of implementation. If there is time, the group will discuss how these fit into the overarching themes of making science efficient, and trying to figure out if these help achieve the greater “goals of science”.

References

National Research Council. 2011. Research Training in the Biomedical, Behavioral, and Clinical Research Sciences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NIH Biomedical Research Working Group Report (2012)

Sauermann H, Roach M (2012) Science PhD Career Preferences: Levels, Changes, and Advisor Encouragement. PLoS ONE 7(5): e36307. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036307

Polka J, (2014) Where will a Biology PhD take you?

(3 votes)

(3 votes)