Wellcome to the Node

Posted by Jonathan Lawson, on 19 April 2011

Hello ‘the Node’, it’s very nice to be here. :) This is the first of my cross-posts between the Wellcome Trust and The Node talking about myself and the research I’m doing in my PhD. You can find my first posts for the Wellcome Trust here and here. I try to write in a way that is accessible to all, so I hope you enjoy them.

Hopefully, science permitting, you’ll be seeing a lot more of me around here and I’m looking forward to meeting many of you at the upcoming BSDB-BSCB spring meeting.

Me, myself and my PhD

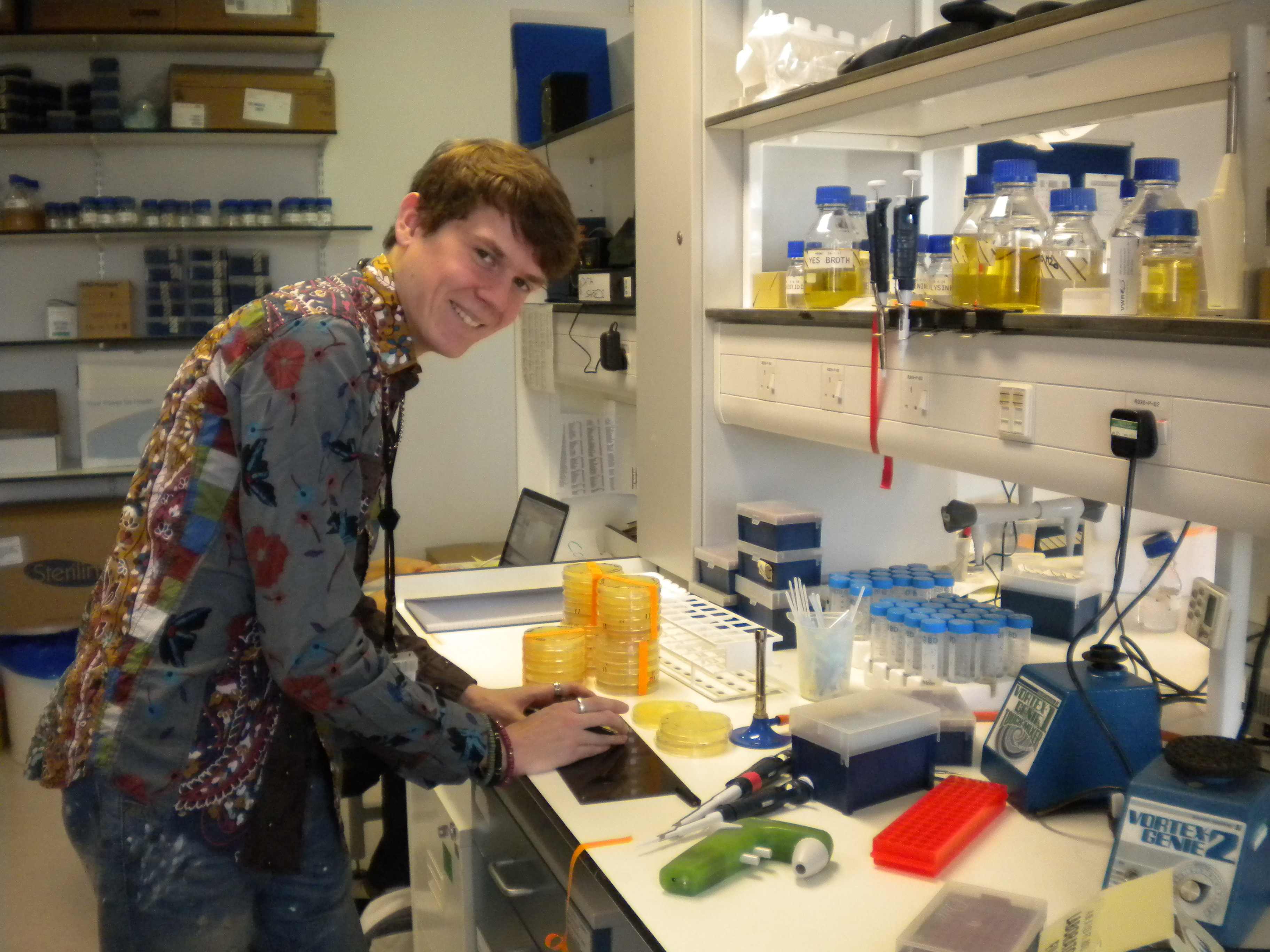

Hi, I’m Jonathan Lawson and I’m here to share my experiences as a developmental biology PhD student in Cambridge. I’m 23 and have already spent four years in Cambridge as an undergraduate, which gave me a BA/MSci in Biochemistry. Although I spend a lot of time in the lab, outside of work I spend a lot of time dancing and my other major passion is baking. I am currently web editor for the student run Cambridge science magazine BlueSci. I am writing these blogs as part of a collaboration between The Node and my benefactors, the Wellcome Trust.

My course is one of the Trust’s Four-year PhD Programmes, it is unusual in that, in the first year, we have a choice of labs we can join, spread across different departments at the University. Each student chooses three labs to join, each for a short nine-week project. This is too short a time to make any significant contributions, but it does allow you to get a good idea of what work is going on in the lab, and whether you will fit in well with the social dynamic. At the end of the first year we choose to join one of these labs for our full 3-year PhD project. This allows students to better understand a lab, and the work, before joining for the long-term, the idea being that students generally feel happier and are more likely to complete their PhD.

I’ll be posting here and on the Wellcome Trust blog occasionally to keep you updated on my research as I move from lab to lab (you can follow a more in depth view of what I do day to day on my own blog. The groups I am working with use a variety of systems to study different aspects of development. I started by looking at chicken development, and worked with a very exciting group of cells found in the nose that have potential to aid regrowth after nerve damage.

Lab 1: The Neural Crest in Chick (Baker Lab)

In mice and rats, cells that guide nerves from the nose into the brain, when transplanted to damaged regions of the spine, help the nerves there to grow through the scar tissue and reconnect with their targets (Barnett and Riddell 2007).

The olfactory nerve, the nerve that tells your brain what you’re smelling, is part of your peripheral nervous system (PNS). Most nerve cells are fixed in place when you are very young, so damage leads to permanent loss of feeling or control. However, the cells you smell with are specialised nerve cells that constantly produce more of themselves.

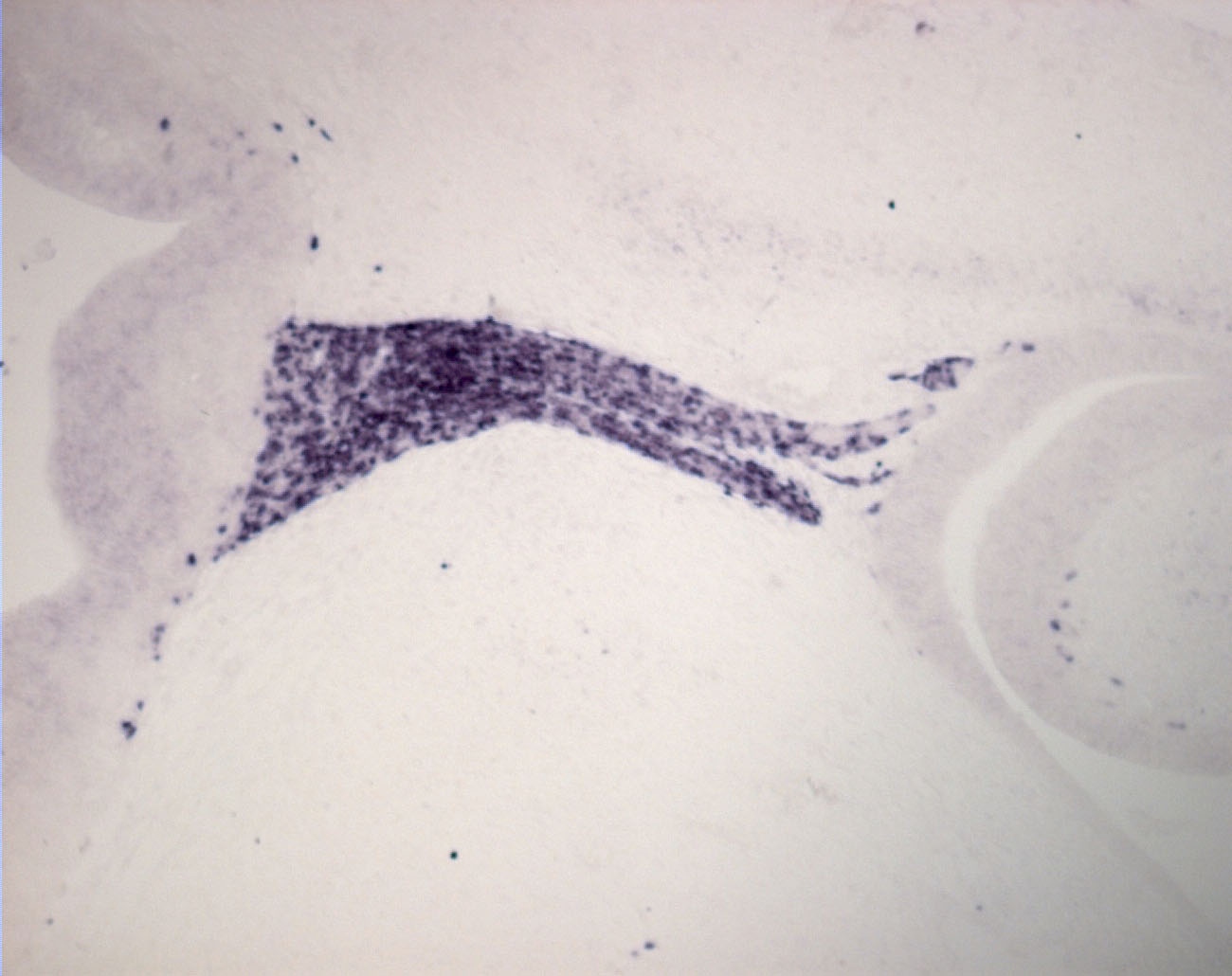

Each new scent receptor nerve cell must signal correctly by extending an axon to the brain. Each axon must connect differently to the brain so smells can be interpreted. Olfactory Ensheathing glial Cells (OECs), unique cells that surround, insulate and protect the nerve axons control axon guidance and ensure correct targetting in the brain.

When the spine is damaged, nerve cells cannot regrow past the damaged region. This is because of astrocytes which build a barrier, which isolates the brain and spine from the rest of the body. In response to damage, astrocytes become highly active and form a scar, which blocks nerve regrowth. This is important to our survival as it stops the brain from becoming infected through the wound, but prevents repair of damaged nerves. OECs suppress astrocyte activity after scar formation and may be able to do so in the context of spinal damage, if provided with the correct signals.

But we can’t use OECs to treat nerve damage right now as there is no easy way to isolate them. Also the effects of OECs on nerve damage have produced varied results depending on the methods used to isolate and introduce cells, so more work is needed, requiring pure samples to study.

This was the focus my first PhD rotation project. My research group recently published a paper showing that during development, OECs travel from a region called the neural crest to the olfactory nerve and with the right signals they can become OECs (Barraud et al., 2010). I am a small part of the project working to find these signals.

Some neural crest stem cells exist in adults, in hair follicles, and so are easy to access. Eventually, by taking a small sample of skin cells from a patient, it could be possible to grow a large group of stem cells and signal them to become OECs. This would form a key part of a treatment for nerve damage. As a patient’s own cells would be used, there should be no immune response to the introduced cells and so no problems with rejection. Additionally, identifying the correct signals may identify markers that will aid purification of OECs from other types of cell.

Besides the obvious therapeutic benefits, OECs are interesting from a purely scientific viewpoint. Cell migration is a very complicated developmental process, as it requires cells to move highly accurately over relatively vast distances. OECs must be correctly positioned in order to guide the olfactory nerve to make proper connections for scent interpretation.

For my next project, I looked at cell polarity in fission yeast. You’ll hear more about that soon. You can also find me on Twitter @clearsci

Read More:

Barnett, S. C. and J. S. Riddell (2007). “Olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation as a strategy for spinal cord repair—what can it achieve?” Nature Clinical Practice Neurology 3(3): 152-161.

Barraud, P., A. A. Seferiadis, et al. (2010). “Neural crest origin of olfactory ensheathing glia.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(49): 21040-21045.

Jessen, K. R. and R. Mirsky (2005). “The origin and development of glial cells in peripheral nerves.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6(9): 671-682.

(4 votes)

(4 votes)

Nice to meet you here Jonathan, Good luck with your research studies.