Forgotten classics- T. H. Morgan and planarian regeneration

Posted by the Node, on 16 February 2016

Morgan, T.H. (1898) Experimental studies of the regeneration of Planaria maculata. Archiv für Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen 7, 364-397

Recommended by Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado (Stowers Institute)

Some classic papers are only cited a few times, and the work therein has been largely forgotten. But that does not mean these works are not worth revisiting. Maybe the paper will have a new impact if interpreted in the context of current science. Maybe it provides insights into the mind of the researcher who wrote it- or the early days of now flourishing fields. This 1898 paper by T.H. Morgan, recommended by Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, is a great example. Given the author’s name, one could have assumed that it was about Drosophila genetics, but it actually concerns planarian regeneration. As Alejandro tells us “Before fruitflies, genetic maps and a Nobel prize, T. H. Morgan spent a significant amount of his budding career studying the problem of regeneration, and favoured as a model the freshwater planarian. For too long were these formative and influential years forgotten or glossed over by most of Morgan’s biographers. Morgan published at least 11 papers on planarian regeneration, and a book on the topic of regeneration (1901).”

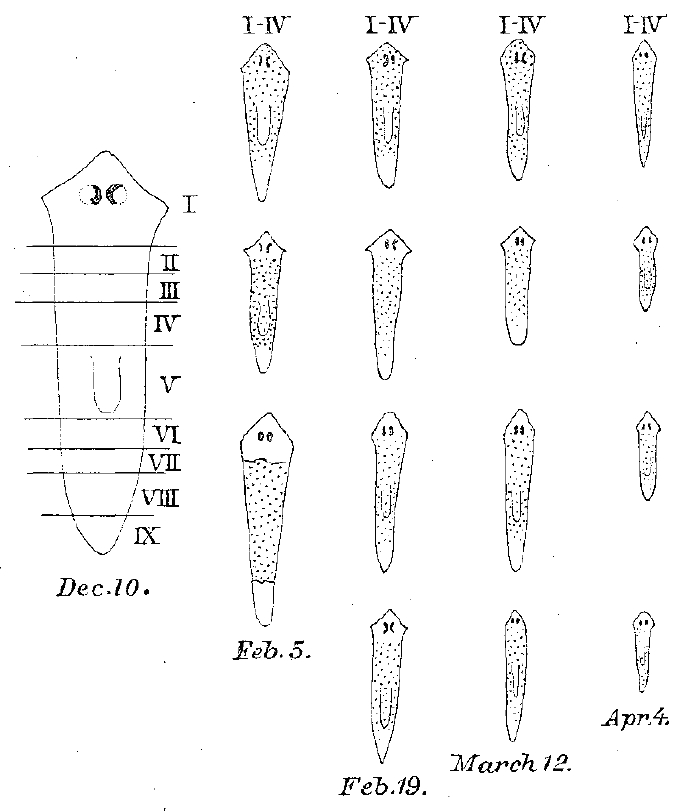

The amazing regenerative abilities of flatworms have been the subject of scientific interest since the end of the 18th century, but much of the observational work done in the early days of the field was forgotten. That is, until more recent times. In the last few decades several planarian regeneration labs have been established and are using modern molecular tools to examine this topic. This 1898 paper is a great example of the observational studies done at the time by scientists interested in regeneration. It is a new field, and no molecular tools are available, so where do you start? At the beginning, of course, which in this case means cutting a lot of planarians and seeing what happens. The paper is written in a wonderfully logical way, and one can follow step by step the thinking process of Morgan. He starts by dividing planarians into several cross sections and examining their regenerative potential. The results observed lead him to address several questions: Is there a limit for how small a fragment can be and still regenerate? Does the shape of the cut play a role? Is remodelling of the old tissues important to ensure that the relative proportions of the regenerated worm are maintained? And are regeneration rates different at the posterior and anterior ends? Morgan does not loose sight of the wider implications of the work and its parallels with normal development. As he states at the end of the paper “The way in which the old tissue transforms itself into a new worm […] show[s] that the material of the body is almost as plastic as that of an undivided or dividing egg”.

Budding regeneration biologists will enjoy following Morgan’s experiments and applying a modern understanding of regeneration to his observations. However, reading this paper will be a delightful exercise even for those outside this field. Modern publishing constraints did not apply in those days, so the work is written almost as a letter to a colleague. It provides a surprisingly candid view of how the experiments were conducted. At one point Morgan writes “About this time I left Woods Holl and carried with me the regenerating pieces, but many of them died as a result, no doubt, of the poor conditions under which they were kept”. This feeling of proximity with the writer and the experiments is accentuated by the figures, which were hand-drawn by Morgan himself. The writing style provides a unique look at the scientist, and this is indeed the reason why Alejandro suggested this paper “I like this particular paper, because it allows us to experience the thought process and experimental reasoning of a brilliant young mind thinking deeply about a complex problem, unaware than in just a few years he would be considered by many the father of modern genetics. The manuscript is an exemplar of clear thinking, elegant and intelligent experimental design”.

Further thoughts from the field

Modern science at times feels too formalized. This paper’s conversational style takes you back to an era of playful, curiosity-driven experimentation and observation. The work was important in cleanly describing important foundational properties of planarian regeneration that we are still struggling to explain to this day.

Peter Reddien, MIT (USA)

As a young graduate student working on Drosophila germ cell development, I became interested in planarian regeneration and started working my way through the classic literature on this topic. Finding Morgan’s early work on planarians was eye opening because it showed how this brilliant scientist approached this problem with the limited tools available to him. Many fundamental discoveries are reported in this paper. For example, he showed that the region in front of the photoreceptors and the pharynx are incapable of regenerating a complete organism. We now know that these regions lack the stem cells that drive planarian regeneration. He also described the amazing remodeling of tissues that restores proper form and proportion to amputated fragments.

Given that we still do not have a satisfactory mechanistic explanation for how these fragments “know” what shape they are supposed to be, it is easy to understand how Morgan made the decision to abandon his work on regeneration in order to study a question that would be more tractable with the tools available to him. In fact, he told a young N. J. Berriill, after hearing that Berrill was working on regeneration in marine worms and ascidian development: “You are being very foolish. I am doing that sort of thing now, as I did when I was very much younger. I can afford to do so now because I am established as the father of genetics in this country and can do what I like. At your age you cannot waste your time. We will never understand the phenomena of development and regeneration.” (Can J. Zool. 61: 947-951, 1983).

Phil Newmark, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (USA)

Springer has kindly provided free access to this paper until the 31st of March 2016!

—————————————–

by Cat Vicente

This post is part of a series on forgotten classics of developmental biology. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

This post is part of a series on forgotten classics of developmental biology. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

(11 votes)

(11 votes)