What Illustrators See that a Camera Can’t

Posted by NatalyaZahn, on 29 August 2017

Illustrator Natalya Zahn on the role of observation and visual interpretation in her work creating an addendum to Nieuwkoop and Faber’s classic Normal Table of Xenopus laevis

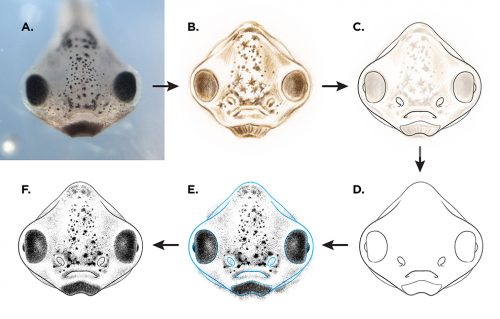

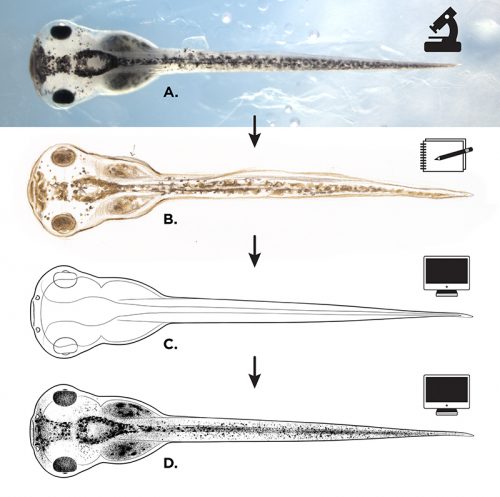

As an artist of science and nature subjects, I’m often asked what makes the work I do better than a photograph. It makes perfect sense to imagine that a direct photographic capture of an object would offer the very most accurate description of that object – and photography certainly is a brilliant format for capturing detail. What that imagination fails to take into account is that a camera must capture everything that it sees in any given shot. Depending on the complexity or ambiguity of the subject, a highly detailed photograph may just as easily overwhelm or confuse a viewer, rather than offer clarification. The beauty of illustration is that it can precisely isolate specific forms or features of a subject, omitting irrelevant details and making clear essential attributes. It is this quality of simplified clarification, produced through execution and interpretation, that can, under the right circumstances, make scientific illustration a more successful form of visual communication than photography.

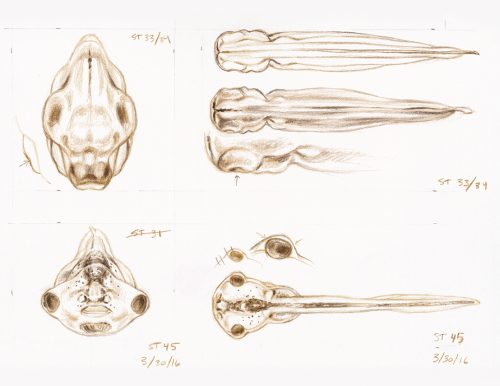

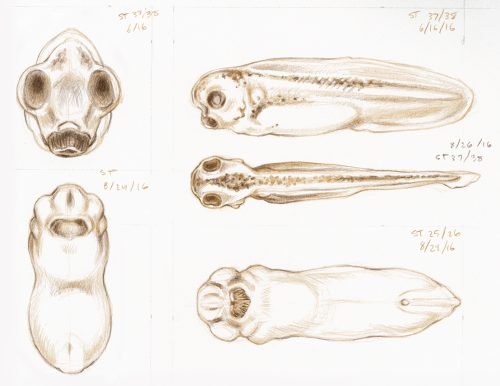

In early 2016 I was commissioned by Dr. Michael Levin and Dr. Dany Adams, at the Tufts Center for Regenerative and Developmental Biology, to create a new series of embryo development illustrations for Xenopus laevis, in the style of Nieuwkoop and Faber’s classic Normal Table, originally illustrated by J. J. Prijs in 1956. The new illustrations would be similar enough in drawing quality so as to seamlessly fit into the existing atlas, but they would feature views of embryos and tadpoles that had not previously been generated (including anterior and ventral views that highlight craniofacial changes).

My work began with many hours observing and sketching live specimens under a Nikon SMZ1500 stereomicroscope; multiple individuals from each stage were used as models. Photographic captures were made using digital micrograph, for later reference, but even high-quality photos can include areas of vague detail. The subtle surface contours in early stage embryos, and the intricacy of numerous visible layers of translucent anatomy in later tadpole stages, made the value of snapshots in time a distant second to my live study. By personally observing numerous embryos of the same stage (taking variation and anomaly into account), and periodically adjusting the angle of my view (to illuminate areas of ambiguity), I was able to completely understand each developmental stage in three dimensions, which brought significantly higher accuracy to my interpretation and rendering of each two-dimensional illustration.

Once I was satisfied with the form and detail of my sketches, I imported each drawing into Adobe Illustrator. Drawing in a vector-based application allowed me to generate the final illustration outlines in extremely clean and consistent line weights. Minimal shading was added in Photoshop, though many of the illustrations are available for use in both shaded and outline-only versions (the later potentially being useful to those interested in adding their own visual notation to an illustration).

My hope for this body of work is that it becomes an invaluable standardized reference for the scientific community, just as Mr. Prijs’ beloved Xenopus illustrations have been for the last half century. Micrographs have only improved since the 1950s but the enduring nature of the drawings within the Nieuwkoop and Faber classic Normal Table is a testament to the enormous teaching power and utility of well executed illustration.

Natalya Zahn is a Boston-based illustrator, designer and visual story-teller. Deeply inspired by animals and nature, her award-winning work explores the intersection of art, design and science and has been featured by National Geographic, Longwood Botanical Gardens, the San Diego Zoo, and MIT Media Lab, among many others. She is skilled in both traditional media and digital techniques, and works fluently across commercial, educational, editorial, and corporate industries.

(10 votes)

(10 votes)

Beautiful post! (And not only bc of the pictures)

I could not agree more on the importance and added value of illustration. A photograph captures a specimen, whereas an illustration can capture the “ideal object”.

It is the same with field guides (for insects or birds): illustrations highlight the features the observer should be looking for and that would be most telling.

Full disclosure: I am biased, although my bias began when Mike Levin and I agreed that Ms. Zahn was the illustrator for the job. That we were right in our choice is abundantly clear from what she has already contributed and what she continues to work on. I had the pleasure of meeting with her this morning, in fact, to discuss the line drawings she is finalizing for the collection. What I did not know in advance was what a good writer she is. Her insights on the value of illustration remind me of the ideas of Dr. Rodolph Sepulchre of Cambridge University concerning what makes a mind different from a computer. While a computer will always be better at computing, a mind has the ability to zero in and ignore, or even forget, that which is unimportant at any given moment. I recommend watching his TedX Talk on you tube: (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXoJJX3GOaQ). I also recommend visiting Natalya.com to zero in on Ms. Zahn’s other insights into Nature.