Imaging by computer and drawing by hand

Posted by Gemma Anderson, on 19 March 2019

An artist and a cultural historian of science visiting the European Molecular Biology Lab (EMBL)

Gemma Anderson (University of Exeter) and Janina Wellmann (MECS, Leuphana University Lüneburg)

Since Steve Woolgar’s and Bruno Latour’s study Laboratory Life was published in 1979 it has become part of the repertoire of STS scholars and anthropologists to visit the sites of science production to study scientific practices and laboratory routines. These visits allow us to build a better understanding of contemporary scientific knowledge in the making, not only epistemologically, but also with respect to institutions, power relations or politics.

In the first week of March we joined the crowd – with the exception that “we” are an artist (Gemma) and a historian (Janina) who teamed up to immerse ourselves into the lab of EMBO Director Maria Leptin, dedicated to the study of cell shape and morphogenesis at EMBL in Heidelberg.

Our interest: Imaging and knowledge production in contemporary biology

For the past decade or two, biology has been undergoing major transformations involving process-oriented and systems-related questions and perspectives on the organism. Live imaging technologies and massive computation are crucial driving forces in this development.

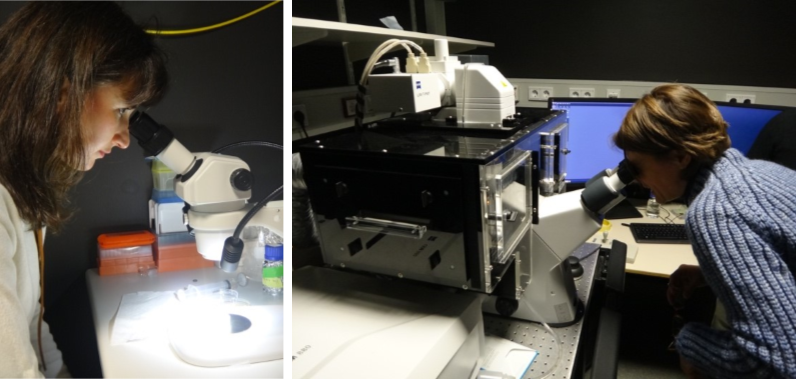

With imaging getting more and more central to biological investigation (the EMBL is currently expanding its site to include a major central imaging facility) it seems ever more relevant to investigate the visual imagery created in those labs from the perspective of the arts and humanities. Indeed, the questions arising are as simple as they are fundamental: What is it that we see? Is seeing still believing, or do we have to reinvestigate that claim critically and ask, with Eric Betzig, winner of the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing super-resolved fluorescence microscopy, “when can we believe what we see?” (Fig.1a,b)

A particular focus and shared interest of ours is the visualization of processes such as gastrulation, that crucial moment early in embryogenesis which is of particular interest to the Leptin group’s research.

How are processes and cell movements during gastrulation accessed with (various kinds of) microscopes1? How do the organism, the images and data extraction relate to one another? What does seeing mean when fluorescence is detected computationally and neither an observer nor binoculars are any longer necessary (even though they are still there, serving the initial positioning of the specimen) (Wellmann 2018)2? Furthermore, for centuries learning how to draw has been part of the biological curriculum and has only recently been drifting out of biological practice and education (Anderson 2014, Steinert 2016)3. Many scientists, however, still think through and with drawings. How do they use drawings to making processes intelligible to themselves, to their colleagues, to people outside their field? Does drawing raise novel questions? And given the strong drive of biology towards investigating processes, movement and organic change, can we conceive of new ways to draw movement and processes?

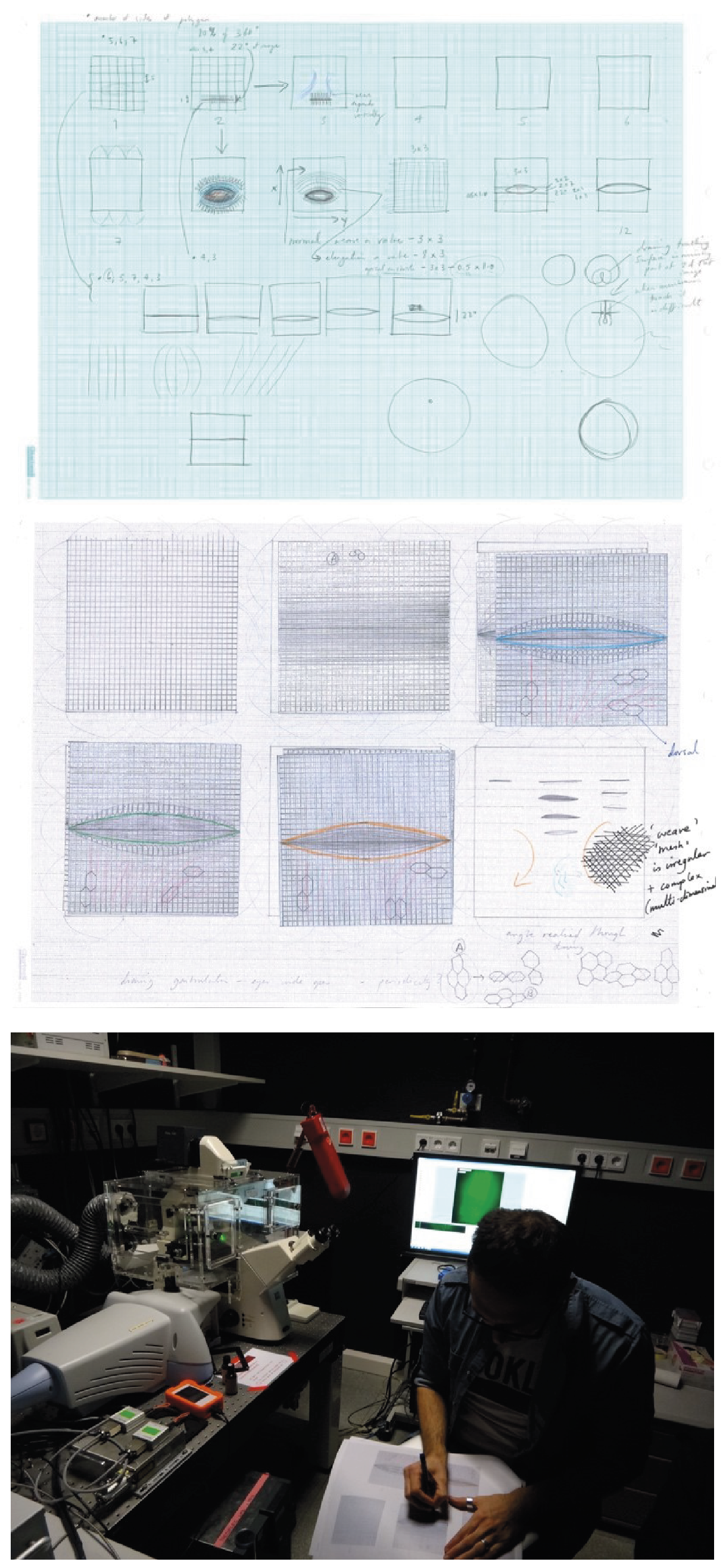

To give an example, Gemma actively introduced drawing as a mode of enquiry to the Leptin lab4. Together with the scientists, Gemma used drawing to investigate new ways to image the whole surface of the gastrulating embryo, including the invaginated area (Fig.2a-c). In the lab, cartographic projections are a favorite pictorial approach, i.e. the 3d body of an embryo is rolled out in a 2d image, just like the globe is flattened to a 2d map of the earth. In the computer-generated images, however, the invaginated area is condensed into a thin line. In working out how to draw the invaginated area of the embryo, Gemma brought novel questions to science while, conversely, learned about the role of actin and myosin, the cellular mesh and the pulses and waves of activity and shape change during gastrulation.

Things we did

For a week, we became observers of and participants in the daily routine of the Leptin group’s research. Housed on the 5th floor, the many different labs of the developmental biology unit line up along busy corridors: the scientists’ benches face the woods or look over Heidelberg and the windowless technical facilities – warm rooms with incubators, cold rooms with refrigerators or rooms equipped with centrifuges – form the core of the building.

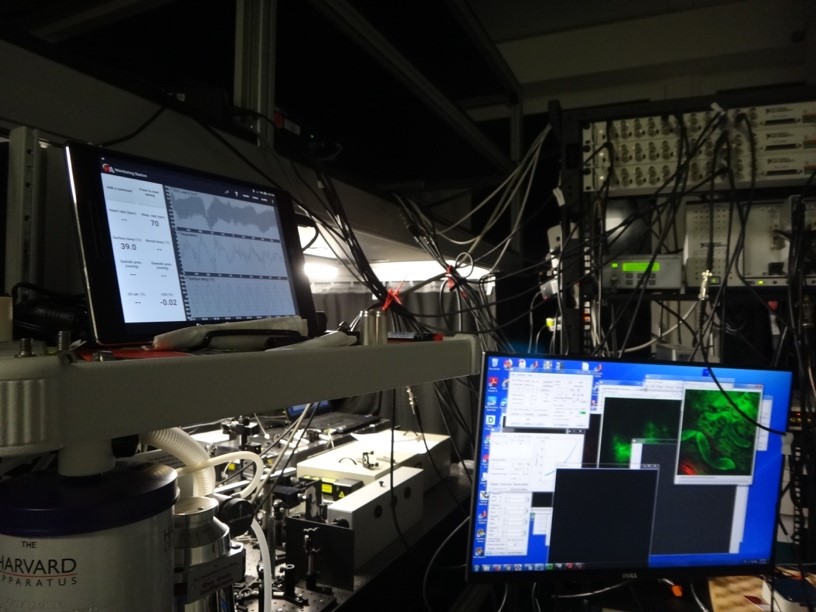

We were introduced to the individual research projects of the doctoral students and post-doctoral researchers (who enthusiastically answered our questions, explained their work and clarified why they were doing what), went to talks (which take place every day, at all times), we gave talks to the lab and observed the mounting of embryos and followed experiments with a variety of different light-sheet, confocal or spinning disc microscopes. We also visited units solely devoted to technological, optical and physical tinkering to develop new imaging devices (Fig.3).

Being exposed to a scientific environment alien to us while exposing the scientists to questions alien to them, it soon became clear that basic words and concepts such as ‘seeing’ and ‘image’ had different meanings, e.g. indicating data to one scientist, model to the other or a specific pictorial form and convention to us. And most importantly, although neatly ordered, separated and organized on different floors and in many labs, research at EMBL takes place where questions and problems cut across disciplines, segmented fields of knowledge and learned practices.

What we think now

Ultimately, engaging in a science – arts – humanities dialogue about contemporary science and image production raises questions as to future human-technology relationships.

Where do we want developments to go? We left the lab wishing to engage in more reflection, discussion and exchange over these developments. Does science follow unswervingly its path in continuing to build ever better technologies? Or ought we rather want to invest (again or more profoundly) in educating scientists (and lay people alike) in their abilities and skills to create images themselves as a unique way of understanding, rather than solely analyzing and handling computer-generated imagery? Notwithstanding technological advances in science, drawing and image making remain a very distinctive form of inquiry and of scientific creativity, bound to human perception and experience.

Thanks

This exposure and arts/humanities experiment would not have been possible without the generous support of the many instances involved: first of all Maria Leptin and the whole lab who allowed us in and devoted their time to us; the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for funding Anderson on the art/science/philosophy project ‘Representing Biology as Process’ (www.probioart.uk) and the DFG-funded Kollegforschergruppe KFOR 1927 for funding Wellmann’s research as well as our home institutions enabling us to be away and to make such a trip possible, the hospitality of EMBL and all its members from the communications department to the technicians – who all followed our work with interest and curiosity.

[1] Janina’s research is part of a DFG-funded project on Media Cultures of Computer Simulation at Leuphana University.

[2] Wellmann, J. 2018 ‘Model and Movement. Studying Cell Movement in Early Morphogenesis, 1900 to the Present’ History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 40:59. https://doi.org /10.1007/s40656-018-0223-0 and Wellmann, J. 2018 ‘Gluing Life Together. Computer Simulation in the Life Sciences: An Introduction History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 40:70. https://doi.org /10.1007/s40656-018-0235-9

[3] Anderson, G. 2014 ‘Endangered: A Study of Morphological Drawing in Zoological Taxonomy’ Leonardo, 47(3), pp. 232–240. For more on the role of drawing and image making in late-19th century embryology see Beatrice Steinert’s blog post for The Node ‘Drawing Embryos, Seeing Development’ 2016 https://thenode.biologists.com/drawing-embryos-seeing-development/discussion/

[4] This visit is part of the AHRC project Representing Biology as Process, www.probioart.uk

The project ‘Representing Biology as Process’ is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council

(1 votes)

(1 votes)