“You have problems with gene regulation, you say?” “Then get rid of the genes!”

Posted by Kalin D. Narov, on 23 August 2012

The purpose of this summary is to present to “The Node” readers a recent update to the story which, in my opinion, is a quite interesting example of the phenomenon of programmed genome rearrangement (PGR) that occurs in the lamprey Petromyzon marinus.

Programmed genome rearrangement describes the regulated structural changes in the genome, which result in the generation of new coding sequences, changes in the control of genome functions and gene expression etc, within ontogeny (not to be confused with similar structural changes on the phylogenetic level). Although on a smaller scale, a form of PGR also occurs during the formation of the T- and B-cell progenitors in mammals, the V(D)J somatic recombination system, which generates the diversity of forms of the Ig- and T-cell receptors.

The PGR in P. marinus occurs during embryonic development and results in the differential deletion of hundreds of millions of base pairs specifically in the genomes of the somatic lineages, as contrasted to the germline. In effect, the germline retains sequences that are deleted in the soma. Of course, this is not the first known case in the Metazoan clade (it has been previously described in sciarid dipterans, nematodes, copepods, etc (see references in the articles cited below)) but according to the authors, it is the first known example of a genome rearrangement of such scale in vertebrates, which makes it especially important for better understanding the evolution and mechanisms of vertebrate gene regulation. Speculatively, lampreys eliminate particular sequences from the somatic tissues’ genomes, which are otherwise important for the complex meiotic rearrangements and pluripotency regulation in the germline, because misregulation of such sequences in the soma may lead to disruptions in genome integrity and defects in cell commitment/differentiation (e.g., tumorigenesis). However, DNA breaks are also visible at later stages of development, which suggests that further rearrangements probably do occur, possibly in a tissue-specific mode (as suggested by variation in the DNA content measured by flow cytometry), which may potentially lead not only to loss of function, but also to the assembly of new sequences (regulatory, coding, etc), that facilitate the differential development of the somatic lineages.

In the newer of the studies, the authors used a customized oligonucleotide microarray that targeted all available germline sequences and a small fraction of the somatic sequences. This revealed that nearly 13% of the screened germline sequences were deleted in the soma and that five of the promising candidate sequences were expressed in the juvenile and adult testes. A large fraction of the somatically deleted sequences are single-copy and protein-coding DNA, which argues against a predominant deletion of repeats. Intriguingly, the authors do not rule out the possibility that whole chromosome elimination may also contribute. Genes presented in the deleted regions include: APOBEC-1, cancer/testis antigen 68, WNT7A/B, SPOPL etc, which in other vertebrates have known roles in cell fate maintenance, proliferation and oncogenesis. Interestingly, some of the genes indentified in the germ-line specific fraction have homologs in other vertebrates where they are not known to function in germline development. I could easily hypothesize that those genes were recruited for germline functions during lamprey evolution or, alternatively, they were germline-specific in ancestral vertebrates but they were later deployed in somatic functions with concomitant loss of germline function. Or it simply means that our knowledge about vertebrate germline function genes is imperfect!

Despite this important differences in genome biology between lampreys and gnathostomes (as we know them), there are many fundamental similarities in embryonic development and gene content. It is expected that some of the factors involved in the lamprey’s PGR will have homologs in gnathostomes. I am curious whether these homologs perform similar functions in jawed vertebrates? Do such PGR mechanisms of a similar scale (excluding the V(D)J system) occur in gnathostomes as well?

From a broader view, these observations suggest that lampreys use an additional strategy for gene regulation as compared to the rest of vertebrates. However, it is important to note that similar PGRs also occur in hagfish (Myxini (please, see the references)). One is prompted to ask: “What is the extent of this process in Myxini? Do their PGRs specifically occur in the soma versus the germline, as in lampreys?” Considering the fact that both lampreys and hagfish use PGRs, it is legitimate to suggest that this strategy of gene regulation was an ancestral system for the early vertebrates, and that the evolution of a gene regulation system predominantly based on epigenetic modification of chromatin was a later invention. However, this is a pure speculation.

Whatever the case is, I imagine that there exist specific DNA sequences that recruit the recombineering machinery (RM) to those regions destined for deletion. Then, it should be of importance that these sequences are occupied by the RM in the particular somatic lineages only and not in the germline. This could be achieved by any of the mechanisms that regulate the function of other regulatory sequences, like enhancers for instance, and may include control of sequence accessibility via epigenetic modification on the chromatin. In addition, tissue-specific expression of the RM components could also be a factor.

Future exploration of the PGR phenomenon will surely provide better understanding of the mechanisms that regulate genome stability, with important implications for cancer biology as well.

References:

Genetic consequences of programmed genome rearrangement, Current Biology, August 21 2012

http://www.cell.com/current-biology/retrieve/pii/S0960982212006732

Programmed loss of millions of base pairs from a vertebrate genome, PNAS, July 7 2009

http://www.pnas.org/content/106/27/11212.long

(5 votes)

(5 votes)

Review: Principles and roles of mRNA localization in animal development

Review: Principles and roles of mRNA localization in animal development Review: Partitioning the heart: mechanisms of cardiac septation and valve development

Review: Partitioning the heart: mechanisms of cardiac septation and valve development (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Gene expression is translationally regulated during many developmental processes. Translation is mainly controlled at the initiation step, which involves recognition of the mRNA 5′ cap structure by the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E). Eukaryotic genomes often encode several eIF4E paralogues but their biological relevance is largely unknown. Here (

Gene expression is translationally regulated during many developmental processes. Translation is mainly controlled at the initiation step, which involves recognition of the mRNA 5′ cap structure by the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E). Eukaryotic genomes often encode several eIF4E paralogues but their biological relevance is largely unknown. Here ( Mammary epithelial cells undergo structural and functional differentiation at late pregnancy and parturition to initiate milk secretion. TGF-β and prolactin signalling act antagonistically to regulate this process but what coordinates these pathways? On

Mammary epithelial cells undergo structural and functional differentiation at late pregnancy and parturition to initiate milk secretion. TGF-β and prolactin signalling act antagonistically to regulate this process but what coordinates these pathways? On  During the development of the central nervous system, neurons and/or neuronal precursors travel along diverse routes from the ventricular zones of the developing brain and integrate into specific brain circuits. Neuronal migration has been extensively studied in the forebrain but little is known about this key developmental event in the embryonic midbrain (mesencephalon). On

During the development of the central nervous system, neurons and/or neuronal precursors travel along diverse routes from the ventricular zones of the developing brain and integrate into specific brain circuits. Neuronal migration has been extensively studied in the forebrain but little is known about this key developmental event in the embryonic midbrain (mesencephalon). On  Anterior-posterior patterning of both the primary embryonic axis and the secondary body axis (limbs and digits) in mammals requires regulated Hox expression. Polycomb-mediated changes in chromatin structure control Hox expression during the first patterning event but are they also involved in the second? Here (

Anterior-posterior patterning of both the primary embryonic axis and the secondary body axis (limbs and digits) in mammals requires regulated Hox expression. Polycomb-mediated changes in chromatin structure control Hox expression during the first patterning event but are they also involved in the second? Here ( Mutations in the human Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome (SBDS) gene, which functions during maturation of the large 60S ribosomal subunit, cause a disorder characterised by exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, chronic neutropenia and skeletal defects. Steven Leach and colleagues have now refined a zebrafish model of this ‘ribosomopathy’ (see

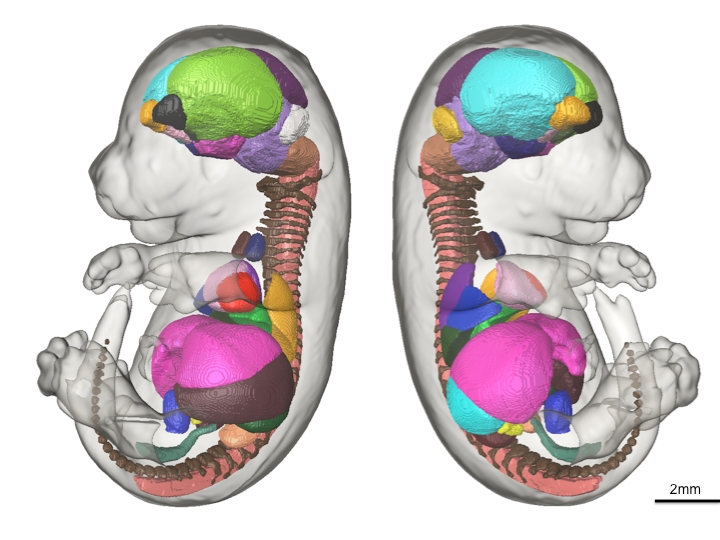

Mutations in the human Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome (SBDS) gene, which functions during maturation of the large 60S ribosomal subunit, cause a disorder characterised by exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, chronic neutropenia and skeletal defects. Steven Leach and colleagues have now refined a zebrafish model of this ‘ribosomopathy’ (see  The sequence and location of every gene in the human genome is now known but our understanding of the relationships between human genotypes and phenotypes is in its infancy. To better understand the role of every gene in the development of an individual, the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium aims to phenotype targeted gene knockout mice throughout the genome (∼23,000 genes). Because many of these mice will be embryonic lethal, methods for phenotyping mouse embryos are needed. Michael Wong and colleagues are developing such an approach and, on

The sequence and location of every gene in the human genome is now known but our understanding of the relationships between human genotypes and phenotypes is in its infancy. To better understand the role of every gene in the development of an individual, the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium aims to phenotype targeted gene knockout mice throughout the genome (∼23,000 genes). Because many of these mice will be embryonic lethal, methods for phenotyping mouse embryos are needed. Michael Wong and colleagues are developing such an approach and, on  The tenth annual RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology symposium ‘Quantitative Developmental Biology’ held in March 2012 covered a range of topics. As reviewed by Davidson and Baum, the studies presented at the meeting shared a common theme in which a combination of physical theory, quantitative analysis and experiment was used to understand a specific cellular process in development. See the Meeting Review on p.

The tenth annual RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology symposium ‘Quantitative Developmental Biology’ held in March 2012 covered a range of topics. As reviewed by Davidson and Baum, the studies presented at the meeting shared a common theme in which a combination of physical theory, quantitative analysis and experiment was used to understand a specific cellular process in development. See the Meeting Review on p.  Meyerowitz and colleagues present a glossary of image analysis terms to aid biologists and discuss the importance of robust image analysis in developmental studies.

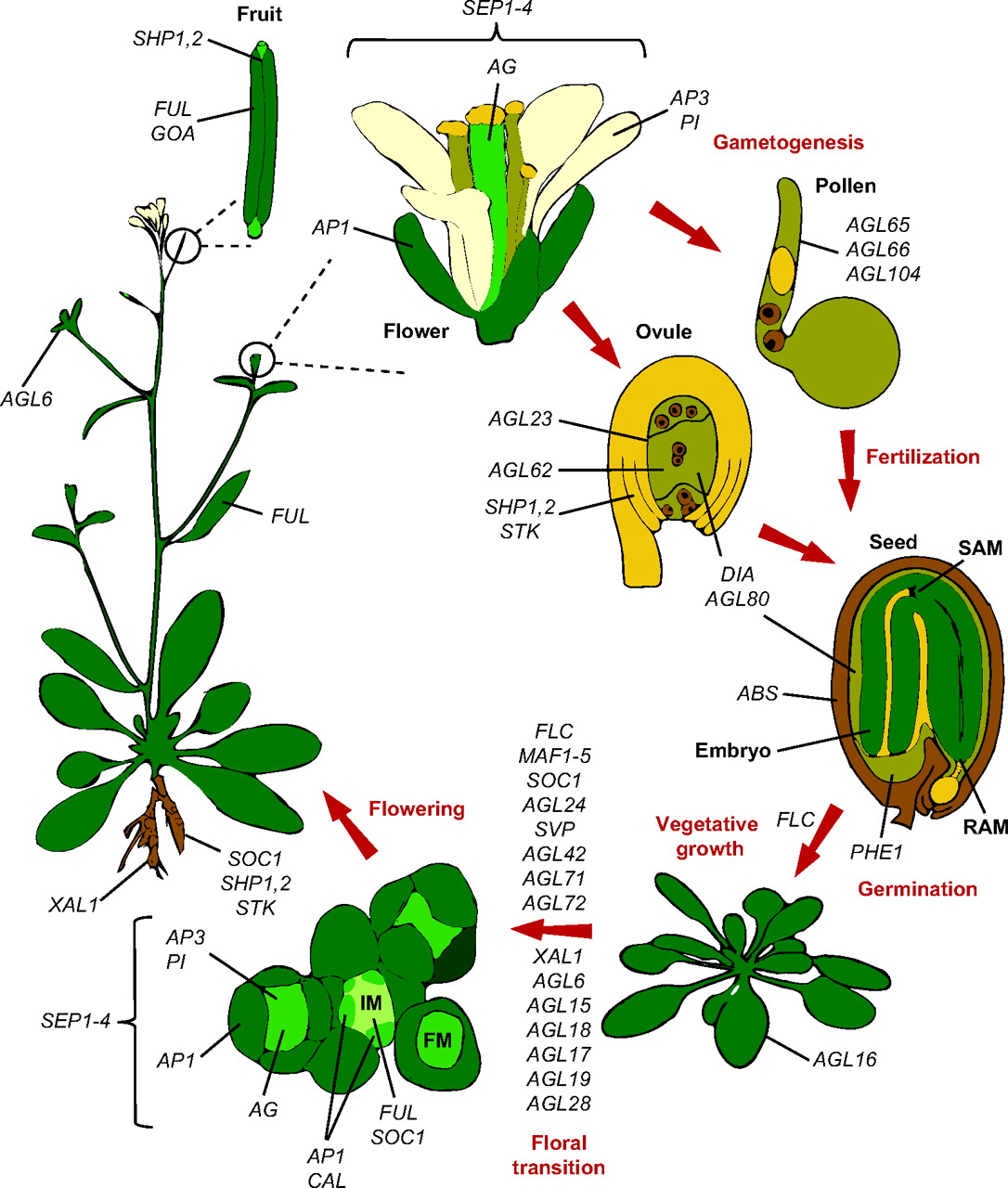

Meyerowitz and colleagues present a glossary of image analysis terms to aid biologists and discuss the importance of robust image analysis in developmental studies. Members of the MADS-box transcription factor family play essential roles in almost every developmental process in plants. Kaufmann and colleagues review recent findings on MADS-box gene functions in Arabidopsis and discuss the evolutionary history and functional diversification of this gene family in plants.

Members of the MADS-box transcription factor family play essential roles in almost every developmental process in plants. Kaufmann and colleagues review recent findings on MADS-box gene functions in Arabidopsis and discuss the evolutionary history and functional diversification of this gene family in plants.