Here are the research highlights from the current issue of Development:

Less air, more muscle repair

Oxygen levels in stem cell niches are often lower than those in surrounding tissues, and hypoxia is known to regulate the self-renewal and proliferation of multiple stem cell types. Now, Shihuan Kuang and co-workers report that hypoxia regulates the ‘stemness’ of satellite cells (muscle stem cells) (see p. 2857). Upon muscle injury, quiescent satellite cells, which lie below the basal lamina of muscle fibres, are activated to proliferate, differentiate and fuse into myofibres, which regenerate the damaged muscle. The researchers show that hypoxic conditions favour satellite cell quiescence by promoting self-renewal divisions without affecting the overall proliferation of primary myoblasts. Hypoxia, they report, activates Notch signalling, which suppresses the microRNAs miR-1 and miR-206, thereby upregulating Pax7, a key regulator of satellite cell self-renewal. Moreover, hypoxic conditioning enhances the efficiency of myoblast transplantation and the self-renewal of implanted cells in vivo. These results identify oxygen level as a physiological regulator of satellite cell activity and suggest that manipulation of oxygen exposure could improve muscle regeneration after injury.

Oxygen levels in stem cell niches are often lower than those in surrounding tissues, and hypoxia is known to regulate the self-renewal and proliferation of multiple stem cell types. Now, Shihuan Kuang and co-workers report that hypoxia regulates the ‘stemness’ of satellite cells (muscle stem cells) (see p. 2857). Upon muscle injury, quiescent satellite cells, which lie below the basal lamina of muscle fibres, are activated to proliferate, differentiate and fuse into myofibres, which regenerate the damaged muscle. The researchers show that hypoxic conditions favour satellite cell quiescence by promoting self-renewal divisions without affecting the overall proliferation of primary myoblasts. Hypoxia, they report, activates Notch signalling, which suppresses the microRNAs miR-1 and miR-206, thereby upregulating Pax7, a key regulator of satellite cell self-renewal. Moreover, hypoxic conditioning enhances the efficiency of myoblast transplantation and the self-renewal of implanted cells in vivo. These results identify oxygen level as a physiological regulator of satellite cell activity and suggest that manipulation of oxygen exposure could improve muscle regeneration after injury.

Embryonic stem cells achieve XEN state

Early mammalian embryogenesis is characterised by a gradual restriction in the developmental potential of embryonic cells. By the blastocyst stage, embryonic and extra-embryonic cells have diverged in their fate and function. However, on p. 2866, Kathy Niakan and co-workers describe a robust method for converting mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst into extra-embryonic endoderm (XEN) stem cells. Previous studies have derived XEN from mESCs by overexpression of Gata4 or Gata6, but here the researchers achieve the same outcome by adding growth factors to a standard culture medium. They confirm that downregulation of the pluripotency transcription factor Nanog and expression of primitive endoderm-associated genes are necessary for XEN cell derivation, and they show that FGF signalling is required to exit mESC self-renewal but not for XEN cell maintenance. Intriguingly, the researchers also show that not all pluripotent stem cells respond equivalently to differentiation-inducing signals. Together, these results suggest that mESCs have a broader differentiation capacity than previously appreciated.

Early mammalian embryogenesis is characterised by a gradual restriction in the developmental potential of embryonic cells. By the blastocyst stage, embryonic and extra-embryonic cells have diverged in their fate and function. However, on p. 2866, Kathy Niakan and co-workers describe a robust method for converting mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst into extra-embryonic endoderm (XEN) stem cells. Previous studies have derived XEN from mESCs by overexpression of Gata4 or Gata6, but here the researchers achieve the same outcome by adding growth factors to a standard culture medium. They confirm that downregulation of the pluripotency transcription factor Nanog and expression of primitive endoderm-associated genes are necessary for XEN cell derivation, and they show that FGF signalling is required to exit mESC self-renewal but not for XEN cell maintenance. Intriguingly, the researchers also show that not all pluripotent stem cells respond equivalently to differentiation-inducing signals. Together, these results suggest that mESCs have a broader differentiation capacity than previously appreciated.

Gut feelings about mesothelial development

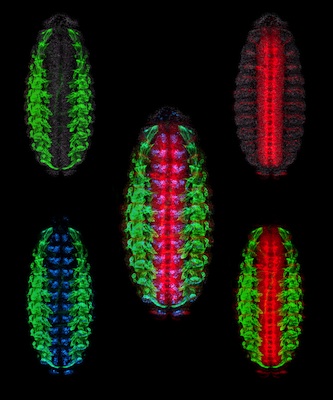

The vertebrate body cavity (coelom) and its internal organs are lined with a simple squamous epithelium called the mesothelium. Mesothelia, which generate the vasculature of coelomic organs, are relatively quiescent in healthy adults but are implicated in pathogenic conditions such as peritoneal sclerosis. The mesothelium of the heart develops from the proepicardium, a localized exogenous population of cells that migrates to and envelops the myocardium; but what are the developmental origins of other mesothelia? Here (p. 2926), David Bader and colleagues identify a novel mechanism for the generation of mesothelia by investigating intestinal development in avian embryos. Using long-term lineage tracing, they show that mesothelial progenitors of the intestine are intrinsic to the gut tube anlage. Moreover, using a new chick-quail chimera model of gut morphogenesis, they show that mesothelial progenitors are distributed throughout the gut primordium and are not derived from a localized, exogenous proepicardium-like source of cells. Thus, cardiac and intestinal mesothelia have strikingly different developmental histories, despite their similarities in ultrastructure and developmental potential.

The vertebrate body cavity (coelom) and its internal organs are lined with a simple squamous epithelium called the mesothelium. Mesothelia, which generate the vasculature of coelomic organs, are relatively quiescent in healthy adults but are implicated in pathogenic conditions such as peritoneal sclerosis. The mesothelium of the heart develops from the proepicardium, a localized exogenous population of cells that migrates to and envelops the myocardium; but what are the developmental origins of other mesothelia? Here (p. 2926), David Bader and colleagues identify a novel mechanism for the generation of mesothelia by investigating intestinal development in avian embryos. Using long-term lineage tracing, they show that mesothelial progenitors of the intestine are intrinsic to the gut tube anlage. Moreover, using a new chick-quail chimera model of gut morphogenesis, they show that mesothelial progenitors are distributed throughout the gut primordium and are not derived from a localized, exogenous proepicardium-like source of cells. Thus, cardiac and intestinal mesothelia have strikingly different developmental histories, despite their similarities in ultrastructure and developmental potential.

Neural lineage pools: REST assured

During nervous system development, coordinated activation and suppression of transcriptional activators and repressors regulates a network of lineage-specific genes that maintains the neural stem/progenitor (NS/P) pool and ensures the orderly acquisition of neural cell fates. Here (p. 2878), Nurit Ballas and colleagues characterise the role played by REST (RE1 silencing transcription factor, a known master repressor of neuronal genes) during neural development. By analyzing the function of REST at different stages of mouse neural development, the researchers show that, although it represses neuronal genes in embryonic stem (ES) cells, it is not required for the maintenance of ES pluripotency or for the conversion of ES cells to neurogenic or gliogenic NS/P cells. REST is required, however, for NS/P cell self-renewal. Moreover, it maintains the proper ratio of neurons and glia during differentiation and regulates genes involved in both neuronal and oligodendrocyte specification and maturation. Thus, REST plays a central role during neural development by regulating the pool size of different neural lineages.

During nervous system development, coordinated activation and suppression of transcriptional activators and repressors regulates a network of lineage-specific genes that maintains the neural stem/progenitor (NS/P) pool and ensures the orderly acquisition of neural cell fates. Here (p. 2878), Nurit Ballas and colleagues characterise the role played by REST (RE1 silencing transcription factor, a known master repressor of neuronal genes) during neural development. By analyzing the function of REST at different stages of mouse neural development, the researchers show that, although it represses neuronal genes in embryonic stem (ES) cells, it is not required for the maintenance of ES pluripotency or for the conversion of ES cells to neurogenic or gliogenic NS/P cells. REST is required, however, for NS/P cell self-renewal. Moreover, it maintains the proper ratio of neurons and glia during differentiation and regulates genes involved in both neuronal and oligodendrocyte specification and maturation. Thus, REST plays a central role during neural development by regulating the pool size of different neural lineages.

The long and short of developmental cell migration

Long-distance cell migration is an important feature of embryonic development, but the mechanisms that underlie these migratory phenomena are unclear. Now, by combining computational modelling and experimental analysis of neural crest (NC) cell migration in chick embryos, Paul Kulesa and co-workers provide a new mechanistic explanation for long-distance cell migration (see p. 2935). The researchers begin by hypothesizing that chemotaxis drives cells to move in a directional manner towards a distant target. This simple model is insufficient, however, to explain their new experimental data. Instead, model simulations that include tissue growth predict that directed NC cell migration requires leading cells to respond to long-range guidance signals and trailing cells to respond to short-range cues. The researchers subsequently identify two NC cell subpopulations with distinct gene expression profiles and cellular orientations within migratory streams, and experimentally confirm model predictions of the effects of exchanging leading and trailing cell positions. Thus, they conclude, a two-component mechanism that includes chemotaxis and cell-cell contact drives long-distance cell migration.

Long-distance cell migration is an important feature of embryonic development, but the mechanisms that underlie these migratory phenomena are unclear. Now, by combining computational modelling and experimental analysis of neural crest (NC) cell migration in chick embryos, Paul Kulesa and co-workers provide a new mechanistic explanation for long-distance cell migration (see p. 2935). The researchers begin by hypothesizing that chemotaxis drives cells to move in a directional manner towards a distant target. This simple model is insufficient, however, to explain their new experimental data. Instead, model simulations that include tissue growth predict that directed NC cell migration requires leading cells to respond to long-range guidance signals and trailing cells to respond to short-range cues. The researchers subsequently identify two NC cell subpopulations with distinct gene expression profiles and cellular orientations within migratory streams, and experimentally confirm model predictions of the effects of exchanging leading and trailing cell positions. Thus, they conclude, a two-component mechanism that includes chemotaxis and cell-cell contact drives long-distance cell migration.

miR-7 fine-tunes pancreatic development

MicroRNAs (short non-coding RNAs that post-transcriptionally silence target mRNAs) are essential for early pancreas development. But how specific microRNAs are intertwined into the transcriptional network that controls endocrine differentiation is poorly understood. On p. 3021, Eran Hornstein and colleagues investigate the involvement of miR-7, which is highly expressed in the endocrine pancreas of several vertebrates, during mouse endocrine cell differentiation. They show that miR-7 is expressed in mouse endocrine precursors and mature endocrine cells, and that the transcription factor Pax6, which is required for endocrine cell differentiation, is an important miR-7 target. The overexpression of miR-7 in developing pancreas explants or in transgenic mice downregulates Pax6 and inhibits α- and β-cell differentiation, they report, whereas miR-7 knockdown has opposite effects. Notably, Pax6 downregulation reverses the effects of miR-7 knockdown on insulin promoter activity. These findings, which suggest that miR-7 and Pax6 are wired into a transcriptional network that ensures the precise control of endocrine cell differentiation, may help in the development of cell-based therapies for diabetes.

MicroRNAs (short non-coding RNAs that post-transcriptionally silence target mRNAs) are essential for early pancreas development. But how specific microRNAs are intertwined into the transcriptional network that controls endocrine differentiation is poorly understood. On p. 3021, Eran Hornstein and colleagues investigate the involvement of miR-7, which is highly expressed in the endocrine pancreas of several vertebrates, during mouse endocrine cell differentiation. They show that miR-7 is expressed in mouse endocrine precursors and mature endocrine cells, and that the transcription factor Pax6, which is required for endocrine cell differentiation, is an important miR-7 target. The overexpression of miR-7 in developing pancreas explants or in transgenic mice downregulates Pax6 and inhibits α- and β-cell differentiation, they report, whereas miR-7 knockdown has opposite effects. Notably, Pax6 downregulation reverses the effects of miR-7 knockdown on insulin promoter activity. These findings, which suggest that miR-7 and Pax6 are wired into a transcriptional network that ensures the precise control of endocrine cell differentiation, may help in the development of cell-based therapies for diabetes.

Plus…

Vascular instruction of pancreas development

Recent studies suggest that blood vessels provide organs with non-nutritional signals that control their development and homeostasis. In this issue, Ondine Cleaver and Yuval Dor review the contribution of the vasculature to developing tissues, with a focus on the pancreas.

See the Review article on p. 2833

Satellite cells are essential for skeletal muscle regeneration: the cell on the edge returns centre stage

In this issue, Frederic Relaix and Peter Zammit review recent recombination-based studies that have furthered our understanding of satellite cells – muscle stem cells. The clear consensus is that skeletal muscle does not regenerate without satellite cells, confirming their pivotal and non-redundant role.

See the Review article on p. 2845

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)