The people behind the papers – Roman Szabo and Thomas Bugge

Posted by the Node Interviews, on 29 January 2020

This interview, the 74th in our series, was recently published in Development.

Dysregulated activity of cell surface proteolytic enzymes has a wide range of developmental and pathological consequences, but the underlying mechanisms are often poorly understood. A new Development paper uses mice to model a severe inherited form of enteropathy and the role of the serine protease matriptase in the disease’s progression. We caught up with first author Roman Szabo and his supervisor Thomas Bugge, Senior Investigator at the NIH National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research in Bethesda, Maryland, to find out more about the story.

Thomas, can you give us your scientific biography and the questions your lab is trying to answer?

TB I did my PhD research at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg working on nuclear receptors, and my postdoc at the University of Cincinnati studying fibrinolytic enzymes. I have been a Senior Investigator at the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Institutes of Health, since 1999. Our laboratory studies how extracellular/pericellular proteases – a group of enzymes several hundred strong – signal to enable vertebrate embryonic development and maintain postnatal tissue homeostasis. We also study how these enzymes, when misregulated, cause human disease. This is a distinctly understudied area, and a fun research space to be in.

Roman, how did you come to work with Thomas, and what drives your research today?

RS As a graduate student I worked with yeasts and how they regulate their cell morphology based on environmental conditions. As the particular species of yeast I was working with typically thrives in a lipid- and protein-rich environment, its behaviour is in part regulated by a battery of proteolytic enzymes that it secretes into the medium in order to digest the proteins to use them as a source of nutrients. After defending my PhD, I was looking for a lab that would allow me to use at least some of that knowledge in experimental systems more related to human physiology. Attracted by both the reputation of the NIH as a leading research institution and Thomas’ impressive prior work in the field of extracellular proteolysis using genetically modified mouse models, I contacted him and it turned out he was just looking for a new postdoc. As I had never worked with mice before, it was probably a bit of a risk, on both our parts, but it was actually quite interesting, and in the end it seemed to have worked out well. And I was lucky that the lab had just started to work on a previously unknown family of proteolytic enzymes that turned out to be quite important for mammalian development and physiology. Learning about different ways in which these enzymes contribute to regulation of various biological processes has been really exciting and, I expect, will keep us busy for the foreseeable future.

How much do we understand about the role of cell-surface proteolytic enzymes in development?

RS & TB Still far too little. These are not the easiest enzymes to work with, at least biochemically. Insights into their developmental functions have been obtained predominantly through the use of reverse genetics in mice and fish, or through the clinical phenotyping of humans and animals with autosomal recessive mutations in their corresponding genes. These efforts have been successful in teasing out a diverse array of functions for individual cell-surface proteolytic enzymes, ranging from sperm maturation to placental development, formation of the feto-maternal interface, auditory system development, tight junction formation, epidermal barrier acquisition, hair growth and skin pigmentation. However, why cell-surface proteolytic enzymes are crucial for so many developmental processes is in large part waiting to be discovered.

And how did you come to work specifically on HAI-2 and matriptase?

RS & TB We came to work with matriptase quite accidentally while performing a screen for novel proteases putatively involved in skin wound healing. As it turned out, one of matriptase’s many developmental functions proved to be skin formation. Alas, we never got round to testing the function of matriptase in skin wound healing, but we have stayed with this fascinating and frustrating enzyme ever since. HAI-2 is structurally quite similar to the well-established matriptase inhibitor HAI-1, so it was an obvious candidate for a second matriptase inhibitor, and, indeed, turned out to be so.

Can you give us the key results of the paper in a paragraph?

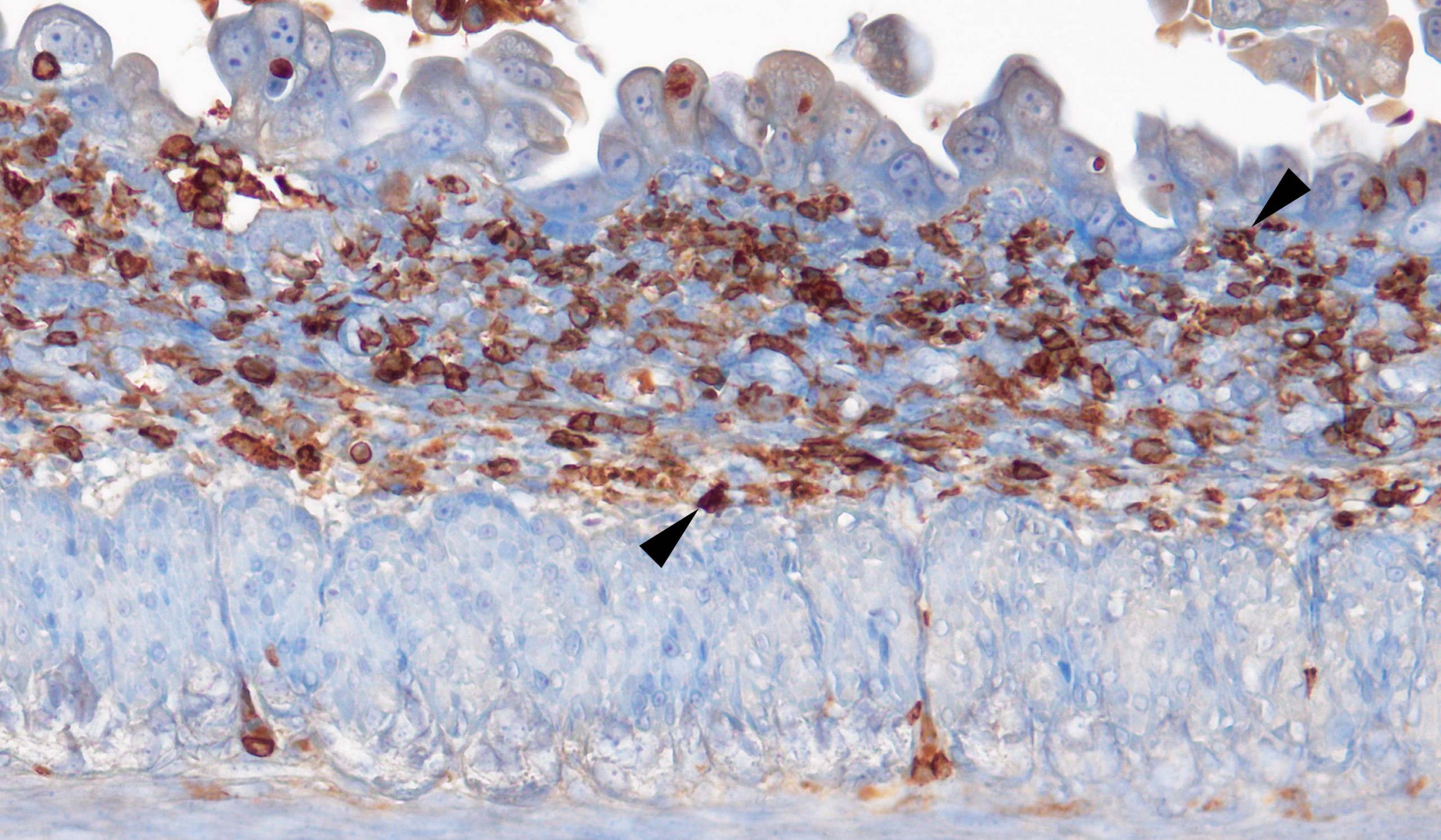

RS & TB We provide evidence that intestinal failure in the syndromic form of the human disease congenital tufting enteropathy (CTE), which is caused by loss of HAI-2, may be due to matriptase hyperactivity. Specifically, we show that conditional ablation of matriptase from the mouse intestine prevents key features of the disease from developing. These include villous atrophy, luminal bleeding, loss of mucin-producing goblet cells, loss of defined crypt architecture and intestinal inflammation. The loss of the cell-cell junction proteins EpCAM and claudin 7 – a hallmark of CTE – was also prevented by the elimination of matriptase from the intestine. Consequently, the mice were able to gain weight and showed extended life-span. The study thus uncovers a potential therapeutic target for this devastating disease.

What do you think HAI-2 is doing, independently of matriptase, in later intestinal development?

RS & TB That is a very good question. HAI-2 is a serine protease inhibitor, so it is only natural to assume that it may need to regulate another serine protease expressed later in intestinal development. Unfortunately, HAI-2 is quite promiscuous, at least in the test tube, where it can inhibit a large number of serine proteases. So it may take a while to track down the culprit.

How might matriptase be targeted therapeutically for CTE?

RS & TB Small molecule active-site inhibitors with selectivity for matriptase would be an obvious choice. Especially inhibitors with poor intestinal absorption that are less likely to affect important functions of matriptase in other parts of the body.

When doing the research, did you have any particular result or eureka moment that has stuck with you?

RS In our research, we rely heavily on designing new genetically modified mouse strains. It can take many months, even years, just to generate animals with the desired gene combination. So after all that work, it is always very exciting for me to see a new phenotype, to be the first person who knows that a certain gene does something really important. In this particular project, it was generating the first HAI-2-deficient mouse, in which elimination of matriptase dramatically increased life-span, and then when the analysis of the tissues from these mice showed that we have indeed prevented the intestinal damage caused by loss of the inhibitor.

It is always very exciting for me to see a new phenotype, to be the first person who knows that a certain gene does something really important

And what about the flipside: any moments of frustration or despair?

RS Not that much on this project, which turned out to be very straightforward. But we did have our share of frustration in the past. Before the invention of new gene targeting technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas, generation of genetically modified mice relied on introducing desired mutations into mouse embryonic stem cells, a process that was inherently ineffective, while at the same time slow and labour intensive. We once spent close to 2 years trying to generate one specific mouse strain, using every tool available to us at the time, before finally having to admit defeat. Similarly, we still lack tools to properly analyse many of the molecules we work with, including matriptase and HAI-2, in living tissues. It can be quite frustrating to have a promising hypothesis and not being able to find a way of testing it.

So what next for you after this paper?

RS Now that we have shown a connection between matriptase activity and intestinal failure in our mice, we would like to understand exactly how matriptase is causing all that damage. There is some evidence that it may do so by cleaving an important structural protein called EpCAM that is frequently lost in patients with CTE. We have already initiated experiments that would help us test whether that is indeed the case. In addition, the function of matriptase and HAI-2 in development is not limited to intestines, and we would like to develop new tools that would help us better analyse both physiological and pathological roles of these two important proteins. And besides my own projects I also have the privilege of organising the next meeting focusing on proteolytic enzymes, the class of proteins matriptase belongs to, which traditionally brings together leading scientists from all over the world to discuss latest advances in the field. It should be an exciting experience.

Where will this work take the Bugge lab?

TB Hopefully one small step further towards understanding the good and the bad side of an enigmatic enzyme, matriptase.

Finally, let’s move outside the lab – what do you like to do in your spare time in Bethesda?

TB Spend time with my wife and enjoy the beautiful nature we are surrounded by.

RS I am a very outdoorsy person so whenever time and weather permit, I like to go hiking, bird watching, wildlife photographing or fossil hunting. Fortunately, there are plenty of opportunities for all that here in the state of Maryland, from the Appalachian mountains to the Atlantic coastline. After a week of work at the bench and behind a computer, it is great to unwind and spend some time with my family going to a park or a beach. My daughter enjoys everything from nature to history and arts, so having a unique collection of national museums in nearby Washington, D.C., also helps.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)