Forgotten classics- Genetic mosaics in Drosophila

Posted by the Node, on 11 May 2016

Bryant, P.J., Schneiderman, H. A. (1969). Cell lineage, growth, and determination in the imaginal leg discs of Drosophila melanogaster. Developmental Biology 20, 263–290

Recommended by Peter Lawrence (University of Cambridge)

The first article in this series was the 1940 paper that first identified the number of cell layers in the shoot meristem. This discovery was possible due to the generation of seed chimeras, where exposure to colchicine generated cells with different ploidy – which could be used as a marker to follow cell lineages. Using genetic mosaics to study development is not unique to the plant field though. Genetic mosaics have been a useful technique in animal models too, in particular in Drosophila where they can be easily generated.

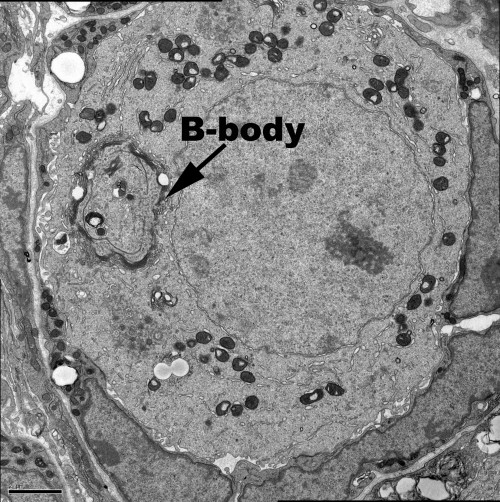

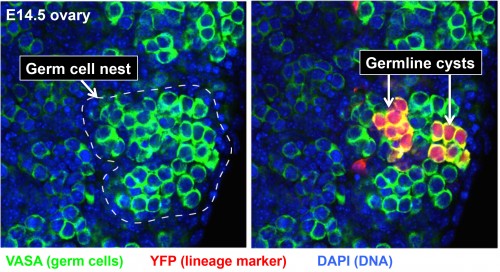

The 1969 paper published by Bryant and Schneiderman in Developmental Biology is a particularly nice example of how genetic mosaics can be used successfully in Drosophila. There are several ways to generate a genetic mosaic in the fly, and two different early techniques were used in this study. Some of the mosaics used were generated by exposing Drosophila embryos, heterozygous for a recessive marker, to X-rays. The X-rays induce double strand chromosome breaks, which when repaired can generate cells that are homozygous for the recessive marker, while the rest of the fly remains heterozygous (apart from the sister clone which is homozygous wild type). This allowed the authors to generate mosaics at specific developmental stages – according to when the animals were exposed to irradiation. They also used another type of genetic mosaic – gynandromorphs. These are female flies which, due to the spontaneous loss of one of the X chromosomes in some of their cells, will be a mix of both male and female tissues. While gynandromorphs spontaneously appear in Drosophila stocks at very low frequency, the percentage of such flies can be increased by using specific stocks carrying a ring X-chromosome, which is lost at higher frequency. Unlike the mosaics generated by X-rays, the loss of the X-chromosome generally occurs very early, thus providing insights into the earliest stages of development.

The 1969 paper discussed here was part of a larger study using genetic mosaics to examine the cell lineages of several organs in the fly. In this paper, Bryant and Schneiderman focused exclusively on cell lineages in the leg. To understand their study, however, it is necessary to consider an additional characteristic of the Drosophila anatomy – the imaginal discs. Before emerging from its pupa as an adult fly, Drosophila spends a period of its life as a very hungry larva. The appendages of the adult fly, such as the eyes, the wings or the legs, are formed upon metamorphosis from bags of epithelium called imaginal discs. To understand how different cell lineages contribute to the formation of the leg, our attention has to focus on the cells of the leg discs.

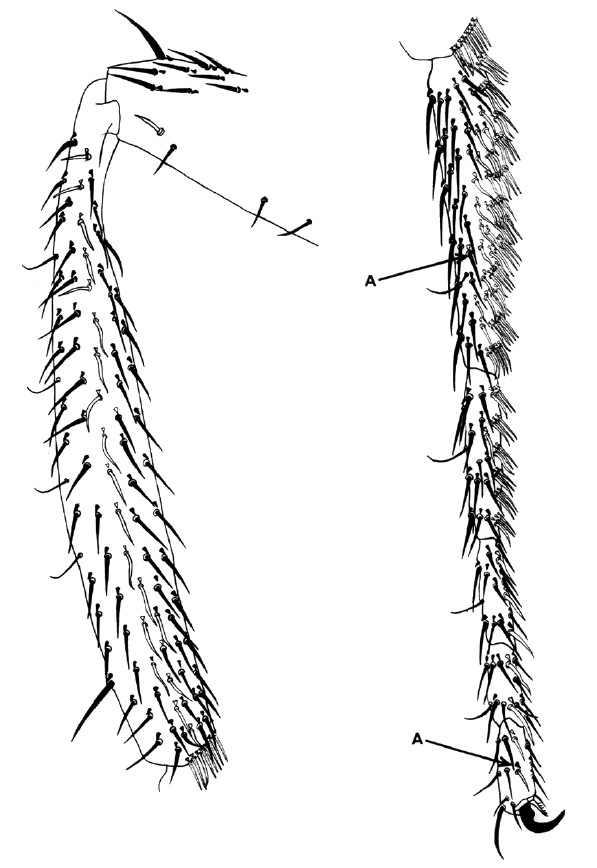

Using X-rays and gynandromorphs, Bryant and Schneiderman produced flies that were mosaics for easily spottable markers affecting the colour and shape of the bristles, the hairs that cover the fly body. They then examined the legs of these mosaic flies. Mosaicism is a game of chance- the size and frequency of clones will depend on the developmental stage when the genetic change takes place or is induced by the X-rays. Using the different types of mosaics generated, they were able to examine different aspects of leg development. For example, they showed that leg disc cells first become ‘determined’ to become leg cells around 3 hours after development begins, around the time when the blastoderm forms. Interestingly though, the cells are not specified to produce specific segments within the leg until much later. They also looked at cell division, showing that these cells do not divide again until later in larval development, and examining how the orientation of division changes. Importantly, they showed that the very first cells that become determined to produce legs are a cluster of 20 cells, rather than a single cell that then multiplies to form a cluster, contradicting a previously proposed theory. Interestingly, although this study made important inroads into understanding the developmental origin and progression of imaginal disc development, the authors missed a few interesting observations. For example, the critically important A/P boundary that exists in the leg (and other) discs is visible in the data presented in this paper, but was not remarked upon by the authors.

While the specific results presented in this paper would have been of particular significance to those studying leg development and imaginal discs, the more general aspects of the work have wider implications. The idea that specific cell lineages are important in the development of structures is taken for granted today, but that wasn’t so in the 60s. As the authors stated, ‘the general significance of cell lineage patterns in development remains a matter for speculation”. It is fascinating to have a first-hand view of the type of work that was conducted to reach this now accepted concept. The paper also provides an interesting insight into this commonly used technique. As Peter Lawrence, who recommended this paper, told us, ‘this is an early paper that illustrates the power of genetic mosaics in finding out how animals are built’.

From the authors:

We were surprised to find that genetically marked clones occupied long narrow strips on the leg, leading to the idea that oriented cell divisions were driving morphogenesis. However, clones on different individuals occupied partially overlapping territories, showing that lineage patterns are indeterminate in this system.

These studies of lineage patterns using gratuitous markers (used only to mark clones, not to affect their development) were followed much later by studies in which one of the two sister clones induced by mitotic recombination had lost the wild-type allele of a tumor suppressor gene. One of the most interesting was the gene we called warts (and others called lats), because clones mutant for this gene were more rounded in shape and had a warty surface texture caused by the secretion of cuticle over a cell layer in which individual cells had a domed apical surface. The discovery of this gene led to the elucidation of the warts/hippo pathway, which turned out to be very important in mammalian cells as well as in Drosophila.

Peter Bryant, UC Irvine (USA)

Further thoughts from the field:

This forgotten classic by Bryant and Schneiderman used and analyzed genetic mosaic clones to gain fundamental insights into the development of the leg imaginal disc of Drosophila. By inducing marked clones at various times in development and then analyzing the location and size of the clones, the authors were able to identify (among other things) the minimal number of cells that gave rise to the leg disc, the point at which the disc begins to proliferate, and the temporal window during which the fate of cells within the leg disc were determined. The governing principles that were uncovered by this study proved to be applicable to the other imaginal discs. A testament to the authors of this study is the fact that over the last 46 years the application of very sophisticated genetic methods by many researchers has only confirmed the results contained with the Bryant and Schneiderman paper of 1969. We should all hope that our papers will stand the test of time as well as this classic study.

Justin P. Kumar, Indiana University (USA)

I remember the Bryant & Schneiderman 1969 paper as the first report of clonal analysis of development by rigorous genetic methods. The method consisted of using X-ray induced mitotic recombination to generate clones of cells in the leg disc (the precursor of the adult leg) labelled with genetic (therefore indelible) markers like yellow (changes the colour of bristles and cuticle), singed (alters the shape of bristles and hairs) or multiple wing hairs (makes several trichomes per cell). The time of irradiation marks the time of clone initiation, so it was possible to generate clones at different developmental stages and to study their potential at different points in development, as well as their size and shape. With these data they could estimate the number of original cells of the disc and the growth rate of the various leg regions. The shape of the clones indicated the orientation of cell divisions in relation with the overall morphology of the adult leg. The paper had a big impact; it inaugurated a series of reports (mainly from Garcia-Bellido and Merrian) describing by this method the development other structures like the wing and the abdomen and eventually all adult structures of the fly.

Ginés Morata, CSIC-UAM (Spain)

Elsevier has kindly provided free access to this paper for 3 months!

—————————————–

by Cat Vicente

This post is part of a series on forgotten classics of developmental biology. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

This post is part of a series on forgotten classics of developmental biology. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

(3 votes)

(3 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet) It is our greatest pleasure to welcome you to the 2016 BSDB autumn meeting that will be held from the 28-30 August in Edinburgh. This conference is our only theme driven meeting for 2016 and provides a unique forum to network and socialise with a wide cross-section of the developmental biology and stem cell community.

It is our greatest pleasure to welcome you to the 2016 BSDB autumn meeting that will be held from the 28-30 August in Edinburgh. This conference is our only theme driven meeting for 2016 and provides a unique forum to network and socialise with a wide cross-section of the developmental biology and stem cell community.