Self assessing your progress as a developing scientist

Posted by David Fay, on 12 February 2026

https://helpimascientist.com/2022/11/20/stages-of-scientific-development/

Posted by David Fay, on 12 February 2026

Posted by the Node, on 11 February 2026

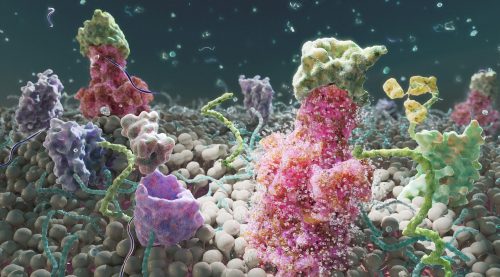

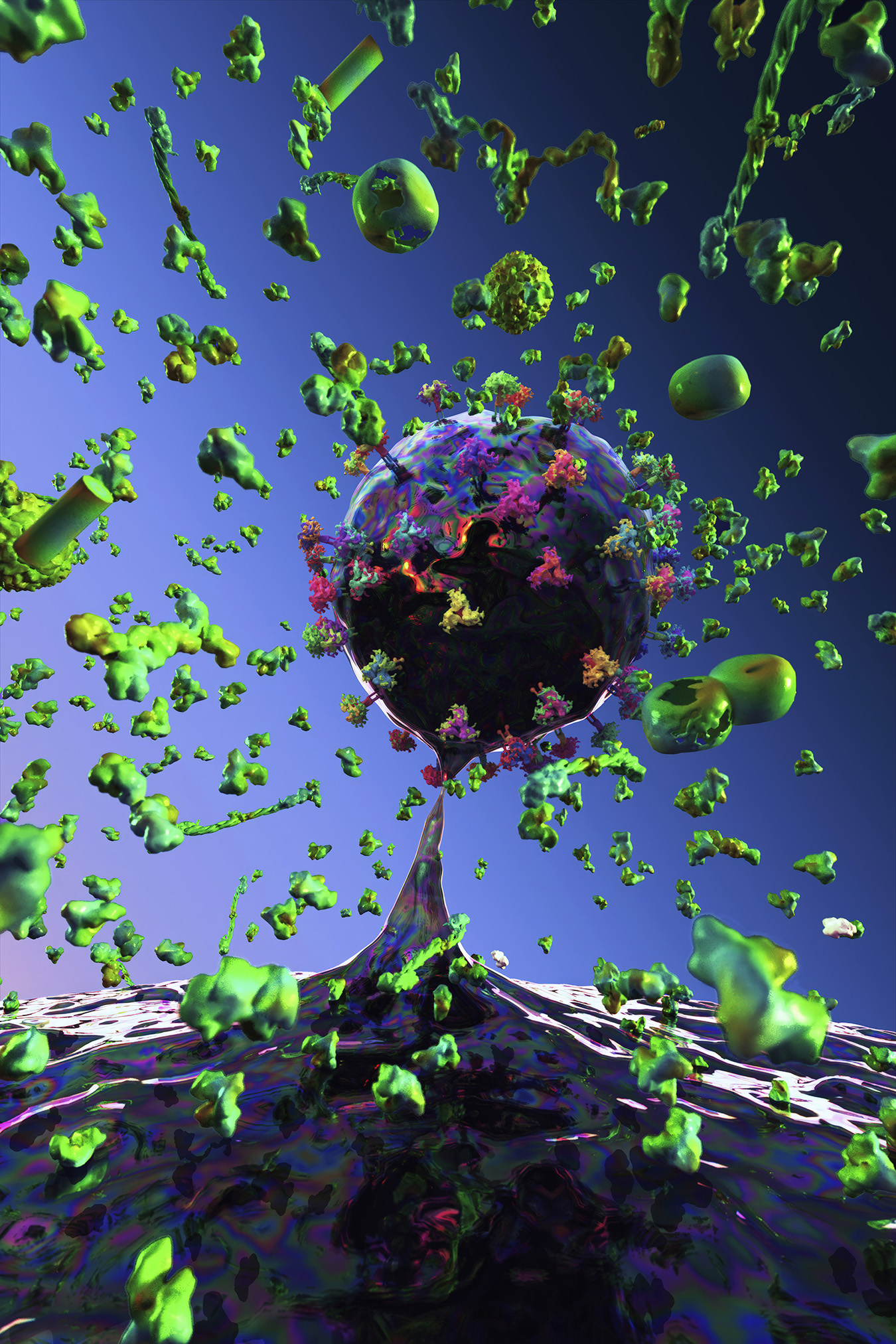

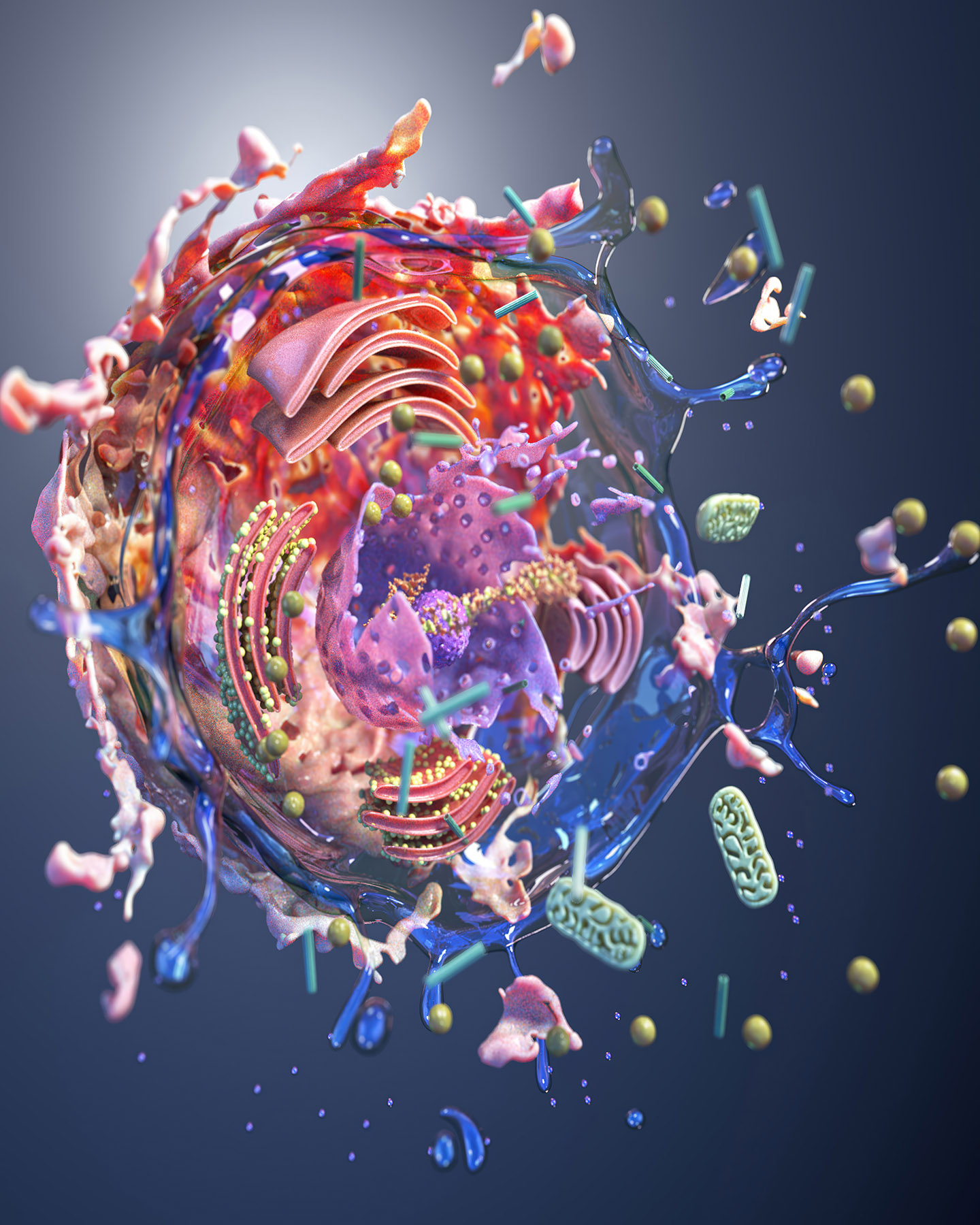

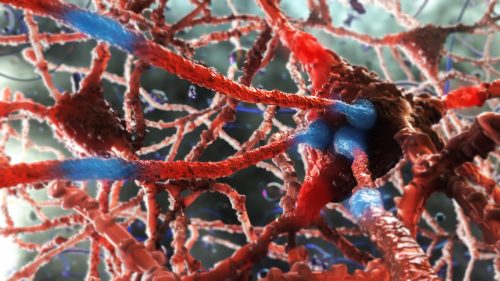

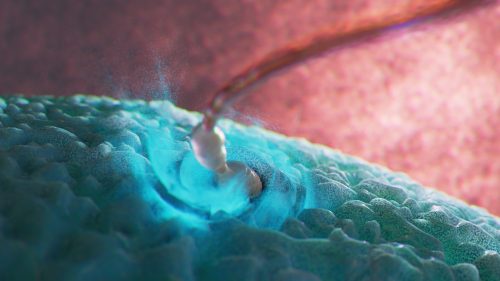

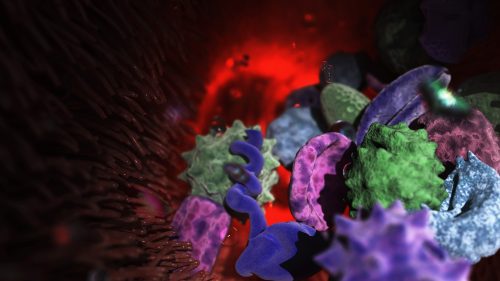

Here we showcase work from Craig Zuckerman, a digital fine artist whose work draws on scientific imagery to create immersive visual environments. With a background in medical illustration and animation, he now works at the intersection of science and fine art, using digital tools to explore form, light, and colour in ways that invite reflection and quiet attention.

Can you describe your artistic practice and how science informs it?

My work transforms cellular and subcellular structures into generative frameworks, moving beyond scientific description into poetic abstraction. Microscopy becomes a language for exploring form, colour, and spatial complexity. Each piece creates a tension between what is biologically recognisable and what is purely atmospheric.

I use scientific structures as scaffolding and use them for creating cinematic environments that resist literal interpretation. My digital work becomes a place to sculpt form, colour, and space with precision, constructing environments that feel immersive and contemplative. Microscopic systems are expanded into vast, navigable landscapes. This shift in scale invites viewers to inhabit the unseen, reframing the body’s interior as a place of wonder, serenity, and emotional resonance.

How do light, colour, and materiality function in your work?

Light functions as a structural force, creating depth and atmosphere. Colour becomes a psychological and emotional driver, guiding the viewer’s experience and transforming biological forms into meditative spaces. These environments invite contemplative gazing. They create a sense of inwardness, mirroring the quiet intelligence of living systems and offering viewers a space for reflection, grounding, and calm.

My limited edition prints on aluminium and plexiglass emphasise physicality, durability, and concreteness. Editioning becomes a conceptual gesture, establishing boundaries around reproducibility and reinforcing the singularity of each work.

Where does your inspiration come from, and how has it informed your artistic practice?

I am a digital fine artist whose work is inspired by science, with a background in medical illustration and animation. My practice marks a deliberate shift from applied science visualisation to autonomous fine art, using cellular structures as generative frameworks rather than clinical subjects.

Now working exclusively in the digital discipline, I construct immersive, cinematic environments in various 3D software that occupy the intersection of abstraction and representation. Colour, light, and composition function as primary structural elements, transforming microscopic systems into expansive spatial experiences. I now use science as a starting point to create biolandscapes.

I have always been influenced by prominent illustrators, from the golden age of illustration through the 1980s, as well as artists from the Renaissance, landscape artists, and sculptors. I continue to create more work in this space, constantly challenging myself with respect to technique, colour, composition, and scientific knowledge.

What advice would you give to others interested in your SciArt approach and where can they find more of your work?

To anyone who has interest in pursuing this approach, it is most important to grow as a visual artist — i.e. use of colour, composition, lighting, drawing and painting skills, or in the software of your choice.

More examples of my work can be found here:

Posted by Arshak Alexanian, on 8 February 2026

Do cells carry memories of the whole body into the next generation?

For more than two millennia, biologists and philosophers have debated whether traits acquired during life can be inherited. From Hippocrates and Aristotle to Lamarck and Darwin, this idea repeatedly surfaced but was ultimately set aside due to the absence of a convincing biological mechanism.

Recent advances in epigenetics have reopened this question.

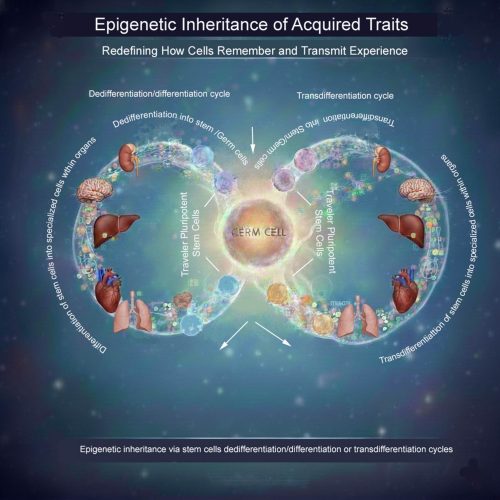

In a recent paper, DOI: 10.1016/j.cdev.2024.203928 I propose a conceptual framework for how environmentally induced epigenetic information might be transmitted from somatic tissues to germ cells—not solely through diffusible molecules, but through cellular movement combined with fate plasticity.

A traveler stem cell hypothesis

The central idea is that certain pluripotent or highly plastic adult stem cells—potentially including germline-associated stem cells—may act as epigenetic travelers. These cells could circulate through the body, enter developmentally active or regenerating tissues, and undergo cycles of differentiation or transdifferentiation in response to local cues. During these transitions, they would acquire tissue-specific epigenetic modifications.

Importantly, these cells would not remain terminally committed. Through dedifferentiation or further transdifferentiation, they could revert to an uncommitted state while retaining accumulated epigenetic information. During gametogenesis, such cells might be recruited back to the gonads, where they ultimately contribute to germ cells—carrying with them epigenetic memory collected across multiple somatic environments.

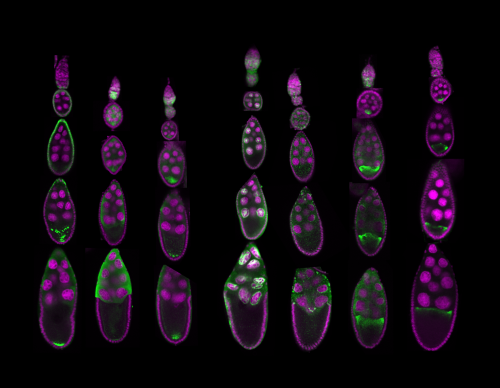

What the image illustrates

The accompanying schematic visualizes this concept: pluripotent “traveler” stem cells move between tissues, repeatedly cycling through differentiation, dedifferentiation, and transdifferentiation. Over time, they integrate epigenetic inputs from diverse organs before re-entering the germline, offering a potential cellular route for soma-to-germline information transfer.

Existing biological foundations

Crucially, elements of this process are not purely hypothetical. Across many multicellular organisms—including plants, invertebrates, and vertebrates—intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance has already been experimentally demonstrated. Epigenetic information can persist through extensive developmental reprogramming events and across multiple generations, indicating that biological systems possess robust mechanisms for preserving epigenetic memory.

Moreover, it has been shown that germ cells or germline-associated stem cells are not irreversibly restricted to reproductive fate. Under specific developmental or experimental conditions, germ cells have been observed to generate diverse somatic cell types. Conversely, somatic or pluripotent stem cells can be induced to acquire germ cell identity and contribute to functional gametes. These bidirectional fate transitions challenge a strict interpretation of the soma–germline barrier and establish that germline and somatic identities are more plastic than traditionally assumed.

Together, these observations provide a biological foundation for considering mobile, fate-plastic cells as integrators and carriers of epigenetic information across tissues.

Why this matters

This framework does not contradict existing models of epigenetic inheritance involving small RNAs or other molecular mediators. Instead, it complements them by addressing a key unresolved problem: how complex, tissue-specific epigenetic states accumulated across an organism’s lifetime might be integrated and transmitted coherently to the next generation.

If experimentally validated, this idea could have implications for developmental biology, evolution, aging, regenerative medicine, and disease inheritance.

A question for the community

If highly plastic stem cells can act as mobile carriers of epigenetic memory, how might we experimentally trace their movements, fate transitions, and epigenetic histories across tissues and generations?

I would welcome thoughts on experimental strategies—or alternative interpretations—that could test or challenge this hypothesis.

Posted by the Node, on 5 February 2026

Welcome to our monthly trawl for developmental and stem cell biology (and related) preprints.

The preprints this month are hosted on bioRxiv – use these links below to get to the section you want:

Research practice and education

Spotted a preprint in this list that you love? If you’re keen to gain some science writing experience and be part of a friendly, diverse and international community, consider joining preLights and writing a preprint highlight article.

Notch signaling in the embryonic ectoderm promotes periderm cell fate and represses mineralization of vibrissa hair follicles

Dianzheng Zhao, Yunus Ozekin, Erin Binne, Irene Choi, Aftab Taiyab, Trevor Williams, Hong Li

A Genetic Mechanism Linking Hippo Signaling to Dorsoventral Patterning for Control of Head and Eye Development

Basavanahalli Nunjundaiah Rohith, Neha Gogia, Arushi Rai, Amit Singh, Madhuri Kango-Singh

An APP-centered molecular gateway integrates innate immunity and retinoic acid signaling to drive irreversible metamorphic commitment

Ryohei Furukawa, Mizuki Taguchi, Narufumi Kameya, Keisuke Tanaka, Haruka Sato, Takehiko Itoh, Yuh Shiwa

MEIS1 is Required for Establishing Bergmann Glia–Specific Properties in the Developing Cerebellum

Kentaro Ichijo, Toma Adachi, Tomoo Owa, Minami Mizuno, Kyoka Suyama, Kaiyuan Ji, Koichi Hashizume, Ikuko Hasegawa, Eriko Isogai, Masaki Sone, Yukiko U. Inoue, Ryo Goitsuka, Takuro Nakamura, Takayoshi Inoue, Satoshi Miyashita, Kenji Kondo, Tatsuya Yamasoba, Mikio Hoshino

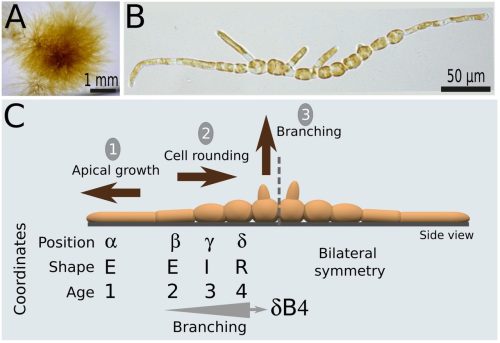

Cell position is more important than cell shape or age for the acquisition of cell identity in the brown alga Ectocarpus

Denis Saint-Marcoux, Bernard Billoud, Sabine Chenivesse, Carole Duchêne, Aude Le Bail, Jane A. Langdale, Bénédicte Charrier

The Joubert gene TMEM67 is required for the correct establishment of spinal dorsal identities in human organoids

Wiegering, K. Bools, I. Anselme, L. Metayer-Derout, O. Mercey, E. Balissat, Y. Bijek, M. Catala, S. Schneider-Maunoury, A. Stedman

Single-Cell Profiling of the Developing Organ of Corti Identifies Etv4/5/1 as Key Regulators of Pillar Cell Identity

Susumu Sakamoto, Matthew W. Kelley

Coordinated inhibition of SOX9 and cell cycle progression by microRNA-200 restricts sebaceous gland fate specification

Arpan Das, Yuheng C Fu, Haimin Li, Megan A. Wong, Annalina Che, Anumeha Singh, Jimin Han, Glen Bjerke, Dongmei Wang, Rui Yi

Smoothened turnover regulated by Hedgehog signaling in Drosophila

Ryo Hatori, Wanpeng Wang, Thomas B. Kornberg

Lipid-mediated reinforcement of FGF/MAPK signaling enables robust otic placode specification

Stephanie R. Peralta, Natalia Maiorana, Michael L. Piacentino

Evidence of autonomous neural specification for both brain and ventral nerve cord tissue in Annelida

Nicole B. Webster, Johnny A. Davila-Sandoval, Allan M. Carillo-Baltodano, Skyler Duda, B. Duygu Özpolat, Néva P. Meyer

Force-dependent stabilization of apical actomyosin by Lmo7 during vertebrate neurulation

Miho Matsuda, Sergei Y. Sokol

Depletion of S100A4+ stromal cells results in abnormal nipple development and nursing failure

Denisa Jaros Belisova, Ema Grofova, Viacheslav Zemlianski, Zuzana Sumbalova Koledova

A Cell Size-Dependent Competition Between Geometry and Polarity Governs Nuclear and Spindle positioning in Early Embryos

Aude Nommick, Macy Baboch, Celia Municio-Diaz, Jeremy Sallé, Remi Le Borgne, Nicolas Minc

Extrinsic MMPs drive epithelial shape change via basal ECM disassembly in the Drosophila wing disc

Chigusa Hinata, Hirotatsu Nakagawa, Shigeaki Nonaka, Katsuya Nozaki, Yoshikatsu Sato, Shizue Ohsawa

A collagen orientation switch reshapes fin architecture

Rintaro Tanimoto, Kazuhide Miyamoto, Koji Tamura, Shigeru Kondo, Junpei Kuroda

Recognizing dUTPase as a mitotic factor essential for early embryonic development

Nikolett Nagy, Otília Tóth, Eszter Oláh, László Henn, Gergely Attila Rácz, Edit Szabó, György Várady, Fanni Beatrix Vigh, Zita Réka Golács, Martin Urbán, Tímea Pintér, Orsolya Ivett Hoffmann, László Hiripi, Hilde Loge Nilsen, Angéla Békési, Miklós Erdélyi, Elen Gócza, Gergely Róna, Judit Tóth, Beáta G. Vértessy

Planar polarization of endogenous ADIP during Xenopus neurulation

Satheeja Santhi Velayudhan, Keiji Itoh, Chih-Wen Chu, Dominique Alfandari, Sergei Y. Sokol

RNA Polymerase III subunit Polr3a is required for craniofacial cartilage and bone development

Bailey T. Lubash, Roxana Gutierrez, Kade Fink, Colette A. Hopkins, Jessica C. Nelson, Kristin E.N. Watt

Cell-cycle inhibition preserves robust development but rebalances lineages in mouse gastruloids

Maxine Leonardi, Yves Paychère, Felix Naef

Distinct roles of the Lyve1 lineage in heart development

Konstantinos Klaourakis, Karolina Zvonickova, Jacinta Kalisch-Smith, Nicola Smart, Duncan Sparrow, David G. Jackson, Paul R. Riley, Joaquim M. Vieira

Spatial Variation in Cortex Glia Cell Cycle Supports Central Nervous System Organization in Drosophila

Vaishali Yadav, Syona Tiwari, Meenal Meshram, Ramkrishna Mishra, Rakesh Pandey, Richa Arya

IAP retrotransposons contribute to the transcriptional diversity of the murine placenta

Samuele M. Amante, Maria L. Vignola, Cyril Pulver, Tessa M. Bertozzi, Anne C. Ferguson-Smith, Marika Charalambous, Miguel R. Branco

MYRF drives heterochronic miRNAs and LIN-42, and amplifies oscillatory programs for stage transitions

Zhao Wang, Shiqian Shen, Xiaoting Feng, Di Chen, Qian Bian, Yingchuan B. Qi

Yin Yang 1-Dependent PcG Function is Essential for TET2 Expression and Early T cell Development

Yinghua Wang, Sahitya Saka, Xuan Pan

A role for HDAC3 in regulating histone lactylation and maintaining oocyte chromatin architecture and fertility

Inês Simões-Gomes, António Jacinto, Ana Pimenta-Marques

The histone code of love: epigenetics of maturation of gonads in the human blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni

Christoph Grunau, Zhigang Lu, Avril Coghlan, Max Moescheid, Thomas Quack, Cristian Chaparro, Eerik Aunin, Jean-Francois Allienne, Adam Reid, Nancy Holroyd, Matt Berriman, Gilda Padalino, Karl F. Hoffmann, Christoph G. Grevelding, Ronaldo de Carvalho Augusto

Histone H3K9 Methyltransferases Regulate Cortical Growth by Coordinating Heterochromatin Formation and Neural Progenitor Dynamics

Sophie Warren, Chris Hemmerich, Ram Podicheti, José-Manuel Baizabal

A developmental timer coordinates organism-wide microRNA transcription

Peipei Wu, Jing Wang, Brett Pryor, Isabella Valentino, David F. Ritter, Kaiser Loel, Justin Kinney, Sevinc Ercan, Leemor Joshua-Tor, Christopher M. Hammell

Identification of germline chromatin modifying factors that influence zygotic transcription activation in C. elegans

Mariateresa Mazzetto, Paige Adekplor, Valerie Reinke

The SynMuvA lin-15A licenses natural transdifferentiation by antagonizing identity safeguarding mechanisms

Sarah Becker, Marie-Charlotte Morin, Julien Lambert, Shashi Kumar Suman, Francesco Carelli, Alex Appert, Stéphane Roth, Sarah Hoff-Yoessle, Jessica Medina-Sanchez, Manuela Portoso, Stéphanie Le Gras, Julie Ahringer, Sophie Jarriault

Decoding the cell intrinsic and extrinsic roles of PRC2 in early embryogenesis

Chengjie Zhou, Meng Wang, Zhiyuan Chen, Yi Zhang

Endogenous retroviral elements LTR8B and MER65 regulate the PSG9 locus that promotes trophoblast syncytialization Insights into placental evolution and pre-eclampsia pathology

Manvendra Singh, Yuliang Qu, Amit Pande, Julianna Zadora, Florian Herse, Martin Gauster, Xuhui Kong, Rongyan Zheng, Rabia Anwar, Katarina Stevanovic, Ralf Dechend, Marie Cohen, Attila Molvarec, Jichang Wang, Miriam K. Konkel, Bin Zhang, Cedric Feschotte, Gabriela Dveksler, Sandra M. Blois, Laurence D. Hurst, Zsuzsanna Izsvák

Single-cell spatially resolved transcriptomic characterization of the developing mouse cochlea

Philippe Jean, Sabrina Mechaussier, Amrit Singh-Estivalet, Céline Trébeau, Aurore Gaudin, Laura Barrio Cano, Andrea Lelli, Fabienne Wong Jun Tai, Sébastien Megharba, Sandrine Schmutz, Sarra Loulizi, Sophie Novault, David Hardy, Carolina Moraes-Cabe, Milena Hasan, Christine Petit, Raphael Etournay, Nicolas Michalski

A conserved C. elegans zinc finger-homeodomain protein, ZFH-2, continuously required for structural integrity and function of alimentary tract and gonad

Antoine Sussfeld, Berta Vidal, Surojit Sural, Daniel M. Merritt, G. Robert Aguilar, Yasmin Ramadan, Oliver Hobert

let-7 miRNA and lin-46 mRNA are the two essential targets of the LIN28 RNA-binding protein in developmental timing

Jana Brunner, Anca Neagu, Dimos Gaidatzis, Lucas J. Morales Moya, Helge Großhans

Conserved Roles of Sp1 in Zebrafish Development and Early Organogenesis

Ankita Sharma, Sudiksha Mishra, Greg Jude Dsilva, Saurabh J Pradhan, Pavan Dev Govardhan, Sanjeev Galande

An Asynchronous Production Line of Meiotic Prophase I in the Mouse Fetal Ovary

Chang Liu, Ziyi Jin, Gan Liu, Guofeng Feng, Jie Li, Yiwei Wu, Hao Jia, Lin Liu

Aging, dauer, and stature phenotypes are conferred by structure-directed missense mutations in the endogenous AGE-1/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit

You Wu, Tam Duong, Neal R. Rasmussen, Kent L. Rossman, David J. Reiner

Mapping of CELF1-RNA interactions reveals post-transcriptional control of lens development

Justine Viet, Matthieu Duot, Agnès Méreau, Yann Audic, Iwan Jan, David Reboutier, Catherine Le Goff-Gaillard, Sarah Y Coomson, Salil A Lachke, Carole Gautier-Courteille, Luc Paillard

microRNAs affecting development of body pigmentation in adult Drosophila melanogaster

Abigail M. Lamb, Jennifer A. Kennell, Eden W. McQueen, Evan J. Waldron, Patricia J. Wittkopp

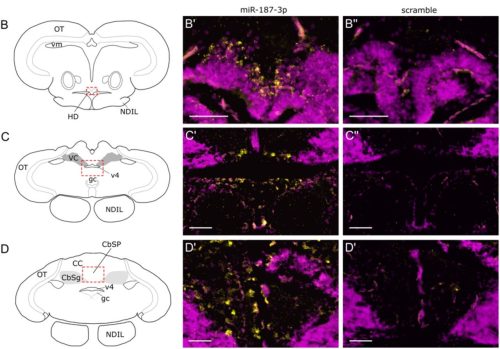

Identification of miR-187 as a modulator of early oogenesis and female fecundity in medaka

Marlène Davilma, Stéphanie Gay, Manon Thomas, Sully Mak, Fabrice Mahé, Laurence Dubreil, Jérôme Montfort, Aurélien Brionne, Julien Bobe, Violette Thermes

Parthenogenote-Derived Brain Unveils the Critical Role of Paternal Genome in Neural Development

Marina Takechi, Yezhang Zhu, Zezhen Lu, Ying Zeng, Ken-Ichi Mizutani, Toru Nakano, Li Shen, Shinpei Yamaguchi

A panoramic view of the expression and function of the Doublesex/DMRT gene family in C. elegans

Chen Wang, Yehuda Salzberg, Meital Oren-Suissa, Oliver Hobert

Lamin A/C directs nucleosome-scale chromatin remodeling to define early lineage segregation in mammals

Alice Sherrard, Liangwen Zhong, Caroline Hoppe, Srikar Krishna, Scott Youlten, Curtis W. Boswell, Stephen Cross, Fiona E. Sievers, Goli Ardestani, Denny Sakkas, Liyun Miao, Zachary D. Smith, Berna Sozen, Antonio J. Giraldez

Prenatal corticosteroid exposure disrupts vascular-immune interactions and impairs steroidogenesis in the fetal testis

Satoko Matsuyama, Lauren Hudepohl, Kazuhiro Matsuyama, Shu-Yun Li, Meghana Ginugu, Xiaowei Gu, Matthew J. Kofron, Vikram Ravindra, Tetsuo Shoda, Tony DeFalco

Hyaluronan underlies the emergence of form, fate, and function in human cardioids

Stefan M. Jahnel, Anna Dimitriadi, Julia Kodnar, Vasileios Gerakopoulos, Yajushi Khurana, Maximilian Mayrhauser, Tobias Ilmer, Keisuke Ishihara, Sasha Mendjan

Profibrotic Changes Following Tension Application in a Fetal Lamb Model of Long Gap Esophageal Atresia

Jessica C. Pollack, Nicolas Vinit, Shelley Jain, Rachel Conan, Melanie Bates, Mia Kwechin, Alicia Eubanks, Mike Xie, Amanda Muir, Emily Partridge

Ybx1 Deficiency Causes ROS-Driven IBD-Like Intestinal Inflammation and Postnatal Lethality

Bo Zhu, Lakhansing Pardeshi, Yingying Chen, Xianqing Zhou, Wei Ge

Dynamic Reorganization of Developmental to Adult Genome Topology Controls the Initiation and Stabilization of the Human Muscle Stem Cell State

Matthew A. Romero, Peggie Chien, Chiara Nicoletti, Hanna L. Liliom, Gabriella Cox, Emily Skuratovsky, Kholoud Saleh, Devin Gibbs, Lily Gane, Dieu-Huong Hoang, Luca Caputo, Jimmy Massenet, Débora R. Sobreira, Pier Lorenzo Puri, April D. Pyle

A single cell atlas defines perinatal factors that drive murine bone marrow development

Brian M Dulmovits, Carson Shalaby, Fangfang Song, James Garifallou, Joshua Bertels, Fanxin Long, Christopher S Thom

Aging disrupts tissue homeostasis and constrains blastema-mediated regeneration in the Cladonema medusa

Ren Kanehisa, Hiroko Nakatani, Sho Takatori, Taisuke Tomita, Masayuki Miura, Yu-ichiro Nakajima

Capturing self-renewing multipotent neural crest stem cells from human pluripotent stem cells

Yayoi Toyooka, Nami Kawaraichi, Daisuke Kamiya, Teruyoshi Yamashita, Yusaku Komoike, Kimiko Fukuda, Teppei Akaboshi, Hirokazu Matsumoto, Makoto Ikeya

Fibroblast-specific Deletion of Yap/Taz Impairs Mouse Postnatal Dermal Development by Suppressing Collagen Production and Deposition

Alexandre, Ava J Kim, Kirk C Hansen, Maxwell McCabe, Jun Young Kim, Zhaoping Qin, Zhaolin Zhang, Tianyuan He, Chunfang Guo, John J Voorhees, Gary J Fisher, Taihao Quan

Activation of developmental transcription factors using RNA technology promotes heart repair

Riley J. Leonard, Mason Sweat, Steven Eliason, William Kutschke, Brad A. Amendt

In vivo xenogenic reconstitution of human alveolar epithelial architecture and function

Akira Yamagata, Satoshi Konishi, Satoshi Ikeo, Hiroshi Moriyama, Senye Takahashi, Naoyuki Sone, Satoshi Hamada, Atsushi Saito, Takashi Kawaguchi, Shu Hisata, Akira Niwa, Toshiaki Kikuchi, Hirofumi Chiba, Megumu K. Saito, Koichi Hagiwara, Toyohiro Hirai, Mio Iwasaki, Takuya Yamamoto, Takeshi Takahashi, Shimpei Gotoh

PI3K inhibitor-free differentiation and maturation of human iPSC-derived arterial- and venous-like endothelial cells

Oliwia N. Mruk, Ralitsa R. Madsen

Scalable high-fidelity human vascularized cortical assembloids recapitulate neurovascular co-development and cell specialization

Shubhang Bhalla, Belda Gulsuyu, Damian Sanchez, Jayden M. Ross, Santhosh Arul, Adnan Gopinadhan, Muhammet Öztürk, Tanzila Mukhtar, Jonathan J. Augustin, Jerry C. Wang, Joseph Kim, Chang N. Kim, Sena Oten, Yohei Rosen, John M. Bernabei, Vijay Letchuman, Shantel Weinsheimer, Helen Kim, Elizabeth E. Crouch, Edward F. Chang, David Haussler, Mircea Teodorescu, Arnold R. Kriegstein, Tomasz J. Nowakowski, Ethan A. Winkler

Isthmin-1 is a Key Regulator of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Cardiomyocytes Maturation through Activation of p53 Signaling

Haowen Guo, Xin Zhou, Yang Shi, Bin Zhou, Jiaqi Tang, Faxiang Xu, Yanchen Guo, Fang Chen, Dongming Su, Qingguo Li

Cellular basis of accelerated whole-tooth regeneration

Talha Mubeen, Haowen He, George W. Gruenhagen, Anoushka Satoskar, Jeffrey T. Streelman

Identification of distinct functions of GLIS3 in β-cell generation critical to prevention of neonatal diabetes

David W. Scoville, Sara A. Grimm, Xin Xu, Benedict Anchang, Anton M. Jetten

Maternal lipids prime quiescent neural stem cells to reactivate in response to dietary nutrients

Md Ausrafuggaman Nahid, Susan E. Doyle, Kelly E. Dunham, Michelle L. Bland, Sarah E. Siegrist

Developmental programming of hematopoietic stem cell dormancy by evasion of Notch signaling

Patricia Herrero-Molinero, Eric Cantón, María Maqueda, Cristina Ruiz-Herguido, Arnau Iglesias, Jessica González, Brandon Hadland, Lluis Espinosa, Anna Bigas

Preconceptional immunomodulation partially corrects pregnancy abnormalities induced by endometriosis in a mouse model, with normalization of transcriptional alterations observed in the developing fetal-maternal interface at the single cell level

Kheira Bouzid, Roxane Bartkowski, Alix Silvert, Fabiana Moresi, Camille Souchet, Marine Thomas, Isabelle Lagoutte, Vaarany Karunanithy, Brigitte Izac, Charles Chapron, Pietro Santulli, Frédéric Batteux, Céline Mehats, Louis Marcellin, Ludivine Doridot

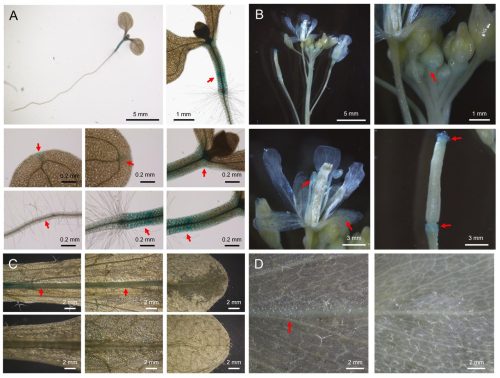

Novel repressors of cambium activity in Arabidopsis

Xing Wang, Jingyi Han, Emma K. Turley, Riikka Mäkilä, Anne-Maarit Bågman, Julia M. Kraus, Qing He, Hanan Alhowty, Joanna Edwards, Yuqi Li, Raluca Blasciuc, Wiktoria Fatz, Wenbin Wei, Miguel de Lucas, Siobhán M. Brady, Shixue Zheng, Chunli Chen, Ari Pekka Mäh-önen, J. Peter Etchells

AGP-Ca2+ binding is essential for pollen development and pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis thaliana

Jessy Silva, Maria João Ferreira, Paul Dupree, Matthew R. Tucker, Maria Manuela Ribeiro Costa, Sílvia Coimbra

Rewiring vascular patterning through translational control in Arabidopsis

Donghwi Ko, Raili Ruonala, Huili Liu, Ondrej Novak, Karin Ljung, Nuria De Diego, Robert Malinowski, Ykä Helariutta

Functional Redundancy of ZmSWEET6a/b in Mediating Sugar Transport and Redox Homeostasis for Maize Primexine Formation

Yan Zhang, Shuangtian Bi, Fengkun Sun, Jiajun Bu, Yurong Wang, Mateus Mondin, Zhaobin Dong, Weiwei Jin, Wei Huang

Arabidopsis GLK transcription factors interact with ABI4 to modulate cotyledon greening in light-exposed etiolated seedlings

Pengxin Yu, Friederike Saga, Miriam Bäumers, Ute Hoecker

Comprehensive characterisation of IAA inactivation pathways reveals the impact of glycosylation on auxin metabolism and plant development

Rubén Casanova-Sáez, Aleš Pěnčík, Federica Brunoni, Anita Ament, Pavel Hladík, Asta Žukauskaitė, Jan Šimura, Ute Voß, Ondřej Novák, Malcolm Bennett, Karin Ljung, Eduardo Mateo-Bonmatí

N-terminal phosphorylation inhibits Arabidopsis katanin and affects vegetative and reproductive development in opposite ways

Vivek Ambastha, Graham Burkart, Rachappa Balkunde, Ram Dixit

A conserved and predictable pluripotency window in callus unlocks efficient transformation in grasses and beyond

Yiyi Wang, Mengjiao Chu, Zhixia Wang, Jinhao Shao, Haijuan Zhang, Zhibiao Nan, Chunjie Li, Lei Lei

Two-step polar plastid migration via F-actin and microtubules ensures unequal inheritance during asymmetric division of Arabidopsis zygote

Keigo Tada, Hikari Matsumoto, Takao Oi, Zichen Kang, Tomonobu Nonoyama, Satoru Tsugawa, Yusuke Kimata, Shuhei Kusano, Shinya Hagihara, Shintaro Ichikawa, Yutaka Kodama, Minako Ueda

Ribosome profiling reveals distinct translational programs underlying Arabidopsis seed dormancy and germination

Maria Victoria Gomez Roldan, Elodie Layat, Julia Bailey-Serres, Jérémie Bazin, Christophe Bailly

Phosphovariants of the canonical heterotrimeric Gα protein, GPA1, differentially affect G protein activity and Arabidopsis development

David Chakravorty, Sarah M. Assmann

Wounding-Induced Redirection of Sugar Transport Fuels Tissue Repair

Rotem Matosevich, Mika Della Zuana, Itay Cohen, Idan Efroni

EARLY FLOWERING 3 (ELF3): a novel role in integrating environmental stimuli with root stem cell niche maintenance

Ali Eljebbawi, Rebecca C. Burkart, Laura Czempik, Vivien I. Strotmann, Xuelei Lai, Mark d. Tully, Luca Costa, Chloe Zubieta, Stephanie Hutin, Yvonne Stahl

The circadian clock gates lateral root development

Sota Nomoto, Allen Mamerto, Shiho Ueno, Akari E Maeda, Saori Kimura, Kosuke Mase, Ayano Kato, Takamasa Suzuki, Soichi Inagaki, Satomi Sakaoka, Norihito Nakamichi, Todd P. Michael, Hironaka Tsukagoshi

Initiation of asexual reproduction by the AP2/ERF gene GEMMIFER in Marchantia polymorpha

Go Takahashi, Saori Yamaya, Facundo Romani, Ignacy Bonter, Kimitsune Ishizaki, Masaki Shimamura, Tomohiro Kiyosue, Jim Haseloff, Yuki Hirakawa

A MICROTUBULE ASSOCIATED PROTEIN is required for division plane orientation during 3D-differential growth within a tissue

Zsófia Winter, Dorothee Stöckle, Takema Sasaki, Sophie Marc Martin, Yoshihisa Oda, Joop EM Vermeer

A shift in developmental allometry underlies the transition to a multi-ovulate strategy from a single-ovulate ancestral state in Phlox (Polemoniaceae)

Bridget Bickner, Elena M Kramer

Auxin coordinates cell states during Arabidopsis root development

Cassandra Maranas, Sydney VanGilder, Linda Nguyen, Jennifer Nemhauser

A chloroplast-localized protein AT4G33780 regulates Arabidopsis development and stress-associated responses

Zhengchao Yang, Zhiming Yu

Root-Suppressed Phenotype of Tomato Rs Mutant is Seemingly Related to Expression of Root-Meristem-Specific Sulfotransferases

Alka Kumari, Prateek Gupta, Parankusam Santisree, Injangbuanang Pamei, Satyavati Valluri, Kapil Sharma, Kavuri Venkateswara Rao, Shivani Shukla, Srilatha Nama, Yellamaraju Sreelakshmi, Rameshwar Sharma

Programming of Embryonic Blood Brain Barrier and Neurovascular Transcriptome by an Anticipatory Acoustic Signal of Heat in the Zebra Finch

Prakrit Subba, Mylene M. Mariette, Katerina A. Palios, Michael G. Emmerson, Elisabetta Versace, Katherine L. Buchanan, David F. Clayton, Julia M. George

Developmental Hypoxia Increases Susceptibility to Cardiac Ventricular Arrhythmias in Adult Offspring

Mitchell C Lock, Kerri LM Smith, Aga Swiderska, Hayat Baba, Andrew Silverwood, Julia Dyba, Olga V Patey, Youguo Niu, Sage G Ford, Freja Steinke, Katherine Dibb, Andrew W Trafford, Dino A Giussani, Gina LJ Galli

Hypoxia couples growth and developmental timing by decoupling steroid synthesis and secretion

George P. Kapali, Alexander W. Shingleton

Early exposure to PFAS disrupts neuro-muscular development in zebrafish embryos

Zainab Afzal, Brian N. Papas, Vandana Veershetty, Evan E Pittman, Charles Hatcher, Jian-Liang Li, Warren Casey, Deepak Kumar

In vitro sexual dimorphism establishment in schistosomes

Remi Pichon, Magda E Lotkowska, Jude L. D. Bulathsinghalage, Madeleine McMath, Mary Evans, Benjamin J. Hulme, Kirsty Ambridge, Geetha Sankaranarayanan, Simon Kershenbaum, Sarah D. Davey, Josephine E. Forde-Thomas, Karl F. Hoffmann, Matthew Berriman, Gabriel Rinaldi

Maternal cardiometabolic dysfunction and fetal sex-specific alterations to uterine vascular reactivity in an ovine model of diet-induced obesity during pregnancy

Rachael C. Crew, Anna L.K. Cochrane, Youguo Niu, Sage G. Ford, Clement L.R. Cahen, Skaai H. Davison, Michael P. Murphy, Susan E. Ozanne, Dino A. Giussani

Prenatal Exposure to Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles Influences Fetal Gut Immunity and Immune Programming

Manuel S. Vidal, Ananth Kumar Kammala, Madhuri Tatiparthy, Ryan C. V. Lintao, Rahul Cherukuri, Ourlad Azeleus Tantengco, Shelly A. Buffington, Enkhtuya Radnaa, Lauren S. Richardson, Ramkumar Menon

Evolutionary dynamics of temporal transcription factor series in the insect optic lobe

Konstantina Filippopoulou, Elisavet Iliopoulou, Claire Julliot de La Morandière, Christy Lee, Marina Marcet-Houben, Toni Gabaldón, Jingyi Jessica Li, Nikolaos Konstantinides

lncRNAs contribute to caste differentiation as a regulatory layer in ants

Guo Ding, Fuqiang Lin, Jixuan Zheng, Dashuang Zuo, Zijun Xiong, Chenyan Liao, Bitao Qiu, Wenjiang Zhong, Jie Zhao, Weiwei Liu, Guojie Zhang

Sex chromosomes and sex hormones contribute jointly and independently to sex biases in cardiac development

Daniel F. Deegan, Gennaro Calendo, Priya Nigam, Raza Naqvi, Arthur P. Arnold, Nora Engel

Mechanically competitive regulation of cell volume in cytoplasm-sharing cells connected by intercellular bridges

Hiroshi Koyama, Kanako Ikami, Lei Lei, Toshihiko Fujimori

Interface-Resolved Proteomics of Cell–Cell Membranes Reveals Early Spatial Polarity in a Vertebrate Embryo

Fei Zhou, Peter Nemes

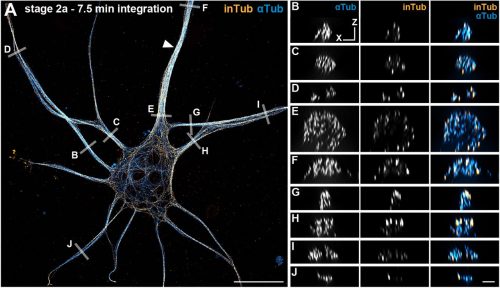

Direct labeling of microtubule turnover reveals in-lattice repair and stabilization patterns in developing neurons

Ciarán Butler-Hallissey, Harrison M. York, Florence Pelletier, Jean-Marc Goaillard, Jérémie Gaillard, Manuel Théry, Pascal Verdier-Pinard, Christophe Leterrier

C. elegans E3 ubiquitin ligase EBAX-1 promotes non-apoptotic linker cell-type death through target-directed miRNA degradation

Lauren B. Horowitz, Olya Yarychkivska, Yun Lu, Shai Shaham

Kinesin-1 trans-synaptically regulates synaptic localization of SARM1 for asymmetric neuron diversification

Anaam Khalid, Peter Sahyouni, Jun Yang, Shengyao Yuan, Rui Xiong, Chiou-Fen Chuang

Lysosome-Related Organelles Orchestrate Guanine Crystal Formation in Pigment Cells

Anna Gorelick-Ashkenazi, Yuval Barzilay, Tali Lerer-Goldshtein, Tsviya Olender, Zohar Eyal, May Glaser, Yonatan Broder, Nadav Mishol, Rachael Deis, Merav Kedmi, Dvir Gur

P-glycoprotein exofection between fetal and maternal cells as a mechanism of intercellular material transfer at the feto maternal interface

Madhuri Tatiparthy, Amanda Wang, Vineeth Mahajan, Pilar Flores-Espinosa, Emmanuel Amabebe, Tilu Jain Thomas, Xiao-Ming Wang, Lauren S Richardson, Ramkumar Menon, Ananth K Kammala

Clocks and Dominoes: Timing Mechanisms of Embryogenesis

Yonghyun Song, Brian D. Leahy, Hanspeter Pfister, Dalit Ben-Yosef, Daniel J. Needleman

Integrative Inference of Spatially Resolved Cell Lineage Trees using LineageMap

Xinhai Pan, Yiru Chen, Xiuwei Zhang

A proteomic signature of oocyte quality from models of varying oocyte developmental competence

Emily R. Frost, Dulama Richani, Anne Poljak, Ananya Vuyyuru, Xuihua Liao, Elise Georgiou, J M Binuri Gunasekara, Bettina P. Mihalas, Irene E. Sucquart, Kaushiki Kadam, Lindsay E. Wu, Robert B. Gilchrist

MorphoLearn: A morphology-driven workflow to decipher 3D electron microscopy segmentation in diatoms

Clarisse Uwizeye, Serena Flori, Jhoanell Angulo, Pierre-Henri Jouneau, Benoit Gallet, Pascal Albanese, Giovanni Finazzi

How simple physics drives the earliest stages of embryogenesisAlaina Cockerell, Peyman Shadmani, Krasimira Tsaneva-Atanasova, David M. Richards

Early multi-omic signatures and machine learning models predict cardiomyocyte differentiation efficiency and enable robust hPSC differentiation to cardiomyocytesAustin K. Feeney, Aaron D. Simmons, Elizabeth F. Bayne, Yanlong Zhu, Mason R. Pentes, Paulo F. Cobra, Jianhua Zhang, Timothy J. Kamp, Ying Ge, Sean P. Palecek

Establishing genetically controlled, closed colonies of an ascidian

The Ciona bio-resource consortium

HoloBio A Holographic Microscopy Tool for Quantitative Biological Analysis

Waira Mona, Maria J. Gil-Herrera, Emanuel Mazo, Daniel Córdoba, Sofia Obando, Maria J. Lopera, Rene Restrepo, Carlos Trujillo, Ana Doblas, Raul Castaneda

Array-CNCC: precise aggregation and arrayed plating facilitate quantitative phenotyping of human cranial neural crest cells and craniofacial disease modelling

Ewa Ozga, Katarzyna M Milto, Martina Demurtas, Lawrence E Bates, Graeme Grimes, Takuya Azami, Jing Su, Carlo De Angelis, Marco Trizzino, Jennifer Nichols, Hannah K Long

Sixteen isotropic 3D fluorescence live imaging datasets of Tribolium castaneum gastrulation

Franziska Krämer, Stefan Münster, Frederic Strobl

Integration of early-stage cryopreservation and cell cycle modulation into a flexible kidney organoid differentiation system

Xiaotian Yan, Jina Wang, Ming Xu, Chunlan Hu, Siyue Chen, Yufeng Zhao, Jiyan Wang, Ruiming Rong, Tongyu Zhu, Weitao Zhang

A robust human airway organoid platform enables scalable expansion and trajectory mapping of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells

Noah Candeli, Lisanne den Hartigh, Nicholas Hou, Andrés Marco, José Antonio Sánchez-Villacaña, Andrea Garcia-Gonzales, Shashank Gandhi, Francesca Sgualdino, Alyssa J. Miller, Jason Spence, Susana Chuva de Sousa Lopes, José L. McFaline-Figueroa, Hans Clevers, Talya L. Dayton

“All-in-one” Single-Cell Proteomic Analysis of Protein Alterations in Human Oocytes Undergoing in Vitro Aging

Jue Zhang, Yuting Lu, Shuoping Zhang, Xingyao Wang, Jiao Lei, Feitai Tang, Shen Zhang, Ge Lin

Real-time single-molecule imaging in zebrafish embryos uncovers non-canonical translation

Maëlle Bellec, Kenny Mattonet, Tatsuya Morisaki, Margaux Lay, Jie Liang, Damien Avinens, Vincent Martinet, Delphine Muriaux, Timothy J Stasevich, Jérémy Dufourt, Didier Y R Stainier

Integration of in situ hybridization and scRNA-seq data provides a 2D topographical map of the developing retina across species

Heer N. V. Joisher, ChangHee Lee, Chaitra Prabhakara, Isabella van der Weide, Yichen Si, Nicholas Lonfat, Constance Cepko

Development and field test of an intervention to reduce conflict in faculty-doctoral student mentoring relationships

Trevor T. Tuma, Emily Q. Rosenzweig, Justin A. Lavner, Yichi Zhang, Erin L. Dolan

Collective AI use is associated with researcher engagement: Real-time evidence from a scientific conference

Hiroyuki Okada, Shigeto Seno, Ung-il Chung, Naganari Okura

The Demographic and GDP Impacts of Slowing Biological Aging

Raiany Romanni-Klein, Nathaniel Hendrix, Richard W. Evans, Jason DeBacker

Leveraging a hybrid cross-disciplinary training model to accelerate global bioinformatics capacity

Taras K. Oleksyk, Daryna Yakymenko, Sylwia Bożek, Viorel Munteanu, Wojciech Pilch, Zoia Comarova, Victor Gordeev, Grigore Boldirev, Dumitru Ciorbă, Viorel Bostan, Christopher E. Mason, Alexander G. Lucaci, Nadiia Kasianchuk, Daria Nishchenko, Victoria Popic, Andrei Lobiuc, Mihai Covasa, Martin Hölzer, Joanna Polanska, Alex Zelikovsky, Vasili Braga, Mihai Dimian, Paweł Łabaj, Serghei Mangul

Cloud-Connected Pluripotent Stem Cell Platform Enhances Scientific Identity in Underrepresented Students

Samira Vera-Choqqueccota, Drew Ehrlich, Vladimir Luna-Gomez, Sebastian Hernandez, Jesus Gonzalez-Ferrer, Hunter E. Schweiger, Kateryna Voitiuk, Yohei Rosen, Kivilcim Doganyigit, Isabel Cline, Rebecca Ward, Erika Yeh, Karen H. Miga, Barbara Des Rochers, Sri Kurniawan, David Haussler, Kristian López Vargas, Mircea Teodorescu, Mohammed A. Mostajo-Radji

Beyond Deficit and Coexistence: Modeling the Knowledge–Conspiracy–Mistrust Configuration in Public Understanding of Science

Ahmet Süerdem, Svetlomir Zdravkov, Martin J. Ivanov

Uncovering Conceptual Biases in DNA Stabilization: A Student-Led Investigation

Charlotte Polo, Ameeta Thandi, Olivia Chandler, Paula Lugert, Alyssa Hammoud, Theertha Madhi, Malena Ayala, A.J. Berrigan, Andrew Chen, Kate Gillett, Sohan Sanjeev, Mya Sareen, Sean Yu, Yang-yang Zuo, Shawn Xiong

Fine-Grained Detection of AI-Generated Writing in the Biomedical Literature

Richard She

Posted by the Node, on 29 January 2026

OurJanuary webinar featured two early-career researchers studying development, evolution and the environment. Here, we share the talks from Chee Kiang (Ethan) Ewe (Tel Aviv University) and Max Farnworth (University of Bristol).

Posted by Alejo Torres Cano, on 28 January 2026

How the project started

If you are in the pancreas field, you may be either part of the endocrine or the exocrine band. Now, this may not be like the Sharks and the Jets in West Side Story, but you better know your position. Whether this separation reflects the actual spatial segregation of both compartments and their different embryonic development is an idea perhaps worth exploring. In any case, our question was linked precisely to that spatial segregation: why do both compartments develop in different regions of the organ?

First of all, we know that what lies around the pancreatic epithelium (what we call the microenvironment) is crucial for its development. Since the 60s1, great works have progressively characterised the microenvironment with greater and greater detail, from early elegant experiments using explants, to more elaborate mouse genetics studies where specific cellular components and signalling pathways were perturbed2,3. The single-cell revolution brought a new twist: the degree of cellular heterogeneity populating the microenvironment, especially mesenchymal cells, was much higher than anticipated. The question then was: how is this heterogeneity spatially distributed?

Mapping the pancreas and deciphering maps.

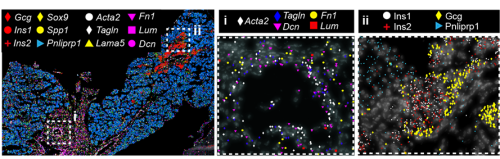

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) appeared to us the best way to answer the question, but at the time we started the project, sequencing-based approaches did not provide the resolution needed to map a small, branched organ like the embryonic pancreas. On the other hand, image-based approaches only allowed for mapping the expression of a handful of markers. Thanks to the early discussions Francesca Spagnoli (PI of the lab) had with Cartana, the biotech at Karolinska Institute, which developed the In Situ Sequencing (ISS) technology and was later acquired by 10x Genomics, we were able to pioneer this approach. In parallel, access to the first single-cell RNASeq datasets of the murine embryonic pancreas -from our lab and others in the field4– enabled us to identify the most informative set of marker genes and design robust panels for the ISS experiments. Running the ISS technology on pancreas was not immediately immediately straightforward; it required considerable effort and a series of optimization experiments carried out by me and another postdoc in the lab., Jean Francois Darrigrand. Finally, by profiling the spatial distribution of sets of markers, we were able to create a cartography of the mouse embryonic pancreas (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 ISS image of selected marker genes in E17.5 pancreas. Close-ups of selected probe genes and their spatial distribution in the tissue are shown in (i) and (ii) dashed boxes.

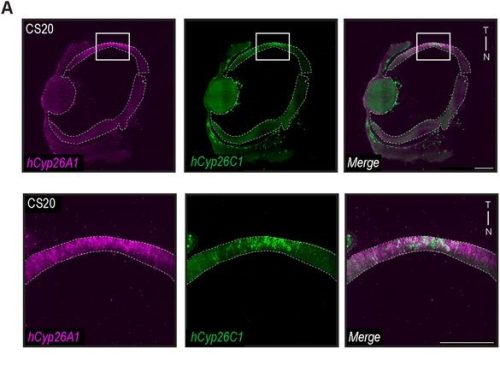

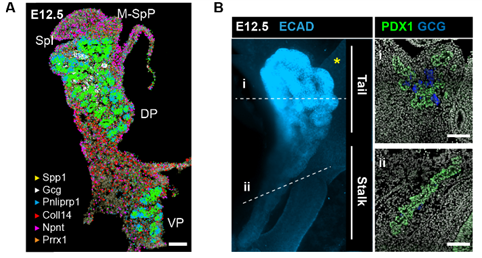

But a map is only an instrument, and the information obtained from it will largely depend on how you read it. When analysing a geographical map, your answers may vary depending on the level of aggregation: you can look at it from the country perspective, zoom in and separate by region or zoom in even more and analyse every city and small town independently. Similarly, when observing an organ, one can use different magnification lenses. First, the pancreas originates from two groups of progenitor cells growing independently (dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds), until they fuse around E14.5 in the mouse embryo. As shown in the 3D images below, generated by a PhD student in the lab, Anna Salowka, the architecture of each bud is not homogeneous along its axes. At the organ level, we discovered that the mesenchyme surrounding the ventral and dorsal pancreas is distinct (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, along the dorsal pancreas -from the duodenum to the region next to the spleen- specific mesenchyme subsets are selectively enriched (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2 (A) Representative ISS image showing selected genes in dorsal pancreas (DP) and ventral pancreas (VP) at E12.5. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Representative three-dimensional (3D) rendering of light-sheet fluorescent microscopy image (left) and confocal microscopy images (right) of E12.5 pancreas stained with indicated antibodies. Right: Confocal IF images show transverse cryosections of DP at tail (i) and stalk (ii) levels. Hoechst was used as nuclear counterstain. Scale bars, 100 μm. Asterisk indicates approximate position of the spleen.

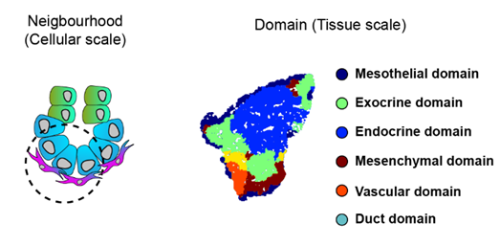

To increase the resolution of our analysis to meso- and micro- scales (Fig. 3), Gabriel Herrera (at the time rotation student in the lab) brough into the project his bioinformatic skills to implement pipelines to analyse the spatial data. What we found is that the tissue is organised in concentrical niches enriched in mesothelial, mesenchymal, exocrine or endocrine cells. When comparing exocrine and endocrine niches, we found that proliferative mesenchyme was preferentially located around acinar cells, whereas another subset, which we termed Mesenchyme (M)-II, was enriched in the endocrine niche.

Fig. 3 Schematics of the spatial analysis frameworks: At cellular scale (left), spatial neighborhoods encompassing the 10 closest cells around each cell were used to calculate cluster pair neighborhood enrichment; at tissue scale (right), tissue areas with similar local cell type composition were clustered to identify tissue domains.

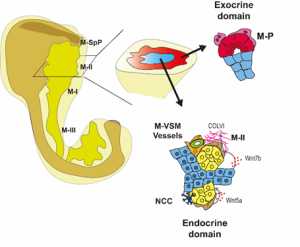

We then focused on the latter association and identified putative Ligand:Receptor interactions between M-II and endocrine cells (Fig. 4). In particular, Wnt5a and Collagen VI molecules caught our attention because of their potential role in creating a niche favourable for endocrine and, specifically, beta-cell differentiation. Consistently, functional experiments using mouse pancreatic explants demonstrated that blocking Wnt5a signaling hampered endocrinogenesis by perturbing the JNK pathway. On the other hand, explants treated with Collagen VI showed a higher number of endocrine cells. By examining human foetal pancreatic tissue, Georgina Goss, a postdoc in the lab, showed that Collagen VI is also enriched around human endocrine cells. Finally, I went on embedding human iPSC-derived endocrine cells in hydrogels containing different ECM mixes, and discovered that Collagen VI, in a conserved fashion, increased the number of beta-cells in the cultures.

To complete our study, we decided to have a glimpse of the adult pancreas. What we found is that different mesenchyme subsets are enriched inside and around islets of Langerhans, ducts and acini. A long-standing question in the field is to track the origin of the adult pancreatic mesenchyme. Our dataset enabled us to fill this gap. Using in silico analysis, we identified fate trajectories connecting the embryonic and adult mesenchyme. Our results suggested that the Spleno-Pancreatic mesenchyme could be one of the origins of the adult mesenchyme which we confirmed using in vivo lineage tracing.

Fig 4: Spatial organization of the pancreatic mesenchyme during embryonic development

What’s next?

Several questions remain open, and several arose during the project. If the pancreatic tissue is carefully distributed, how is that architecture shaped? What signals link epithelial compartments to the formation of their surrounding microenvironment? Our results also raise questions regarding the function of the different levels of organisation: Why does pancreas development need gradients of signalling along the proximodistal axis? It would be interesting to test whether the disruption of that axis causes defects in the separation of the pancreas and surrounding organs. Further research is also needed to understand the function of the secretion of specific ECM components, such as Collagen VI, around exocrine and endocrine cells. In the case of Collagen VI, it would be interesting to investigate how it affects tissue stiffness, as it has been shown that control of the mechanotransducer YAP is crucial for endocrinogenesis. Finally, the spatial organization of the microenvironment during human embryonic development needs further characterization, but using similar approaches we are now beginning to understand it, so if you want to know a little bit more about it, check out the new preprint from the lab5.

Access the article: Torres-Cano, A., Darrigrand, J. F., Herrera-Oropeza, G., Goss, G., Willnow, D., Salowka, A., Ma, S., Chitnis, D., Rouault, M., Vigilante, A., & Spagnoli, F. M. (2025). Spatially organized cellular communities shape functional tissue architecture in the pancreas. Sci Adv, 11(46), eadx5791. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adx5791

References

1. Golosow, N. & Grobstein, C. Epitheliomesenchymal interaction in pancreatic morphogenesis. Developmental Biology 4, doi:10.1016/0012-1606(62)90042-8 (1962/04/01).

2. L, L. et al. Pancreatic mesenchyme regulates epithelial organogenesis throughout development – PubMed. PLoS biology 9, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001143 (2011 Sep).

3. C, C. et al. A Specialized Niche in the Pancreatic Microenvironment Promotes Endocrine Differentiation – PubMed. Developmental cell 55, doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2020.08.003 (10/26/2020).

4. Byrnes, L. E. et al. Lineage dynamics of murine pancreatic development at single-cell resolution. Nature Communications 2018 9:1 9, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06176-3 (2018-09-25).

5. Goss, G. et al. Mesodermal-niche interactions direct specification and differentiation of pancreatic islet cells in human multilineage organoids. bioRxiv, 2025.2012.2013.694117, doi:10.64898/2025.12.13.694117 (2025).

Posted by the Node, on 27 January 2026

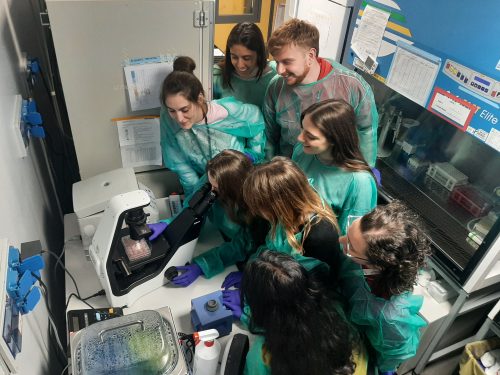

This is part of the ‘Lab meeting’ series featuring developmental and stem cell biology labs around the world.

Andrea: You can find the Ditadi lab at Ospedale San Raffaele, as part of the San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, in the north-east corner of Milan, Italy. Milan is a great spot for both science and life, with a myriad of places to visit, plenty of things to do and a rich community of great labs to collaborate with.

Regarding us, you can find more on our LinkedIn page and our official website.

Andrea: We want to understand how human blood cells form. For this, we use human pluripotent stem cells as a model, integrating developmental, cell and molecular biology, as well as a bit of immunology. We study human developmental biology in a dish: we study early mesoderm patterning and follow the process all the way to mature blood cells, including hematopoietic stem cells, trying to work out which signals guide each step. We are developmental biologists working at an institute that focuses on genetic diseases and their therapy, so we also use the cells we generate to look at diseases from a developmental perspective. At the same time, we explore how to engineer and arm these cells in unique ways so they can be used in clinical settings in the future.

Let’s start in order of length of service in the lab.

We have Lauren Randolph, post-doctoral fellow, who is studying how hemogenic cells give rise to blood.

Claudia Castiglioni, PhD student, who aims to identify the earliest commitment to blood cell fate.

Riccardo Piussi, former Master’s student now PhD student-wannabe (and hopefully soon-to-be), working to decipher the regulation of self-renewal in emerging HSCs.

Deborah Donzel, a postdoctoral fellow, and Nikita Pinto, another former Master’s student now turned research assistant, are partners in modeling a ribosomopathy that affects red blood cells only postnatally to decipher proteostasis regulation across different stages of hematopoietic development.

Elena Morganti, a postdoctoral fellow, and Bianca Nesti, a Master’s student, who teamed up to model a pediatric autoimmune disease as a way to understand the role of embryonic lymphocytes in health and disease.

Alessandra Guerreschi, a Master’s student who recently joined our lab and is gearing up to investigate the multiple roles of Notch signaling in hematopoietic development.

Andrea: It is not exactly a technique, but my favourite moment in the lab is simply watching cells under the microscope. We do not do much imaging; most of our days are spent in the hood doing cell culture. Even now, when I am sadly not doing many experiments any longer, I still have this habit that I actually stole from my postdoc advisor. When I need a break from the desk and the administrative tasks, I go to the lab for what I call a bit of “cell therapy”. I grab a few plates and spend some time simply looking at cells under the microscope. I love it. Observing cells in cultures is very informative, cells talk to us all the time.

If I need to choose a proper technique, I would choose flow cytometry. We use it a lot. It may not be as high-throughput as some newer methods, but it gives us robust full gene expression data at the single-cell level, and we can learn a lot from what comes out of the cytometer.

Andrea: Recently, I have been following the evo-devo field with a lot of interest. I find it fascinating to think about how cells and tissues evolved, and for a lab like ours that tries to recreate how blood cells are formed in vitro, understanding how they appeared in the first place feels very relevant.

Another field that I find extremely exciting is synthetic biology. I am fascinated by how we can now “prod” cells and systems and modify their responses. I remain a developmental biologist at heart, but the environment where we work has opened my eyes to how we can push the boundaries of therapeutic innovation. Alongside the clinical application of stem cells, synthetic biology is transforming the way we think about medicine and how we might design future therapies.

Andrea: I am not sure I can say I am set into one approach, at least yet. I think it is always evolving, as the people in the lab, as well as the lab itself, need change over time. In general, I try to spend time getting to know the people in my group, recognizing the strengths and weaknesses, and trying to exploit the former while helping them work on the latter. I often think of the group as an orchestra or a music band. First, I need to hear the sound of each instrument, help them get tuned and then my job is to compose some music that fits them. Let’s say that some composition takes more time than others. But in the end, the goal is to nurture the love and passion for the true privilege of doing research for everyone.

As for managing the different tasks, I often wish I had more hours in the day; that would be a great superpower. So, I try to clear out the things I do not enjoy, the administrative duties and emails, as quickly as possible. This gives me protected time for what I love: reading, thinking and spending time with the team in the lab. I am not sure I always find enough time for that, but I try very hard.

AD: Without a doubt, being surrounded by young and bright people. It is energizing and another privilege of this job.

CC: The thing I value most about being at SR-Tiget is the stimulating environment, where science truly comes alive. Ideas are shared freely, we have the resources to bring them to life, and we constantly get to learn from seminars by scientists from around the world.

NP: The best thing about working at SR-Tiget in Milan is the combination of different scientific topics and a truly collaborative environment, where you can walk into a lab or an office to ask for help and know that someone will genuinely take the time to help you solve a problem.

RP: What I like most about where I work is the general drive of the institute to do high-level science and to set ambitious goals. In the lab, I really appreciate the way we reason scientifically and the fact that we constantly challenge our ideas by asking questions every day.

LNR: The best thing about where I work is the science and the people. I really enjoy the project that I am working on and find it both challenging and engaging. I am also really lucky to work with incredibly collaborative and supportive colleagues who really treat the lab as a family. It makes it a joy to spend time with them, both in and out of work, and to do and talk science together.

DD: The best things about where I work are the research topic and the people I work with. My enthusiasm for the project keeps me focused and driven, even during challenging periods. I’m also fortunate to work with colleagues who are open to sharing ideas and knowledge, which creates a collaborative environment that helps us move forward together.

BN: What I appreciate most about working at SR-Tiget is the highly stimulating scientific environment, both at the institute level and within my own laboratory. The presence of diverse expertise, frequent seminars and strong resources fosters a continuous exchange of ideas and supports high-quality research.

EM: What I like most about where I work is the young and supportive environment. I feel that people around me are genuine and open-minded, and this makes my days very pleasant and enjoyable.

AG: Even though I haven’t been here long, I’ve really noticed how welcoming and supportive everyone is. It makes it easy to ask questions, learn quickly and feel like part of the team right away.

AD: Despite being in love with my job and not feeling the need to escape, life is too short, and I have so many interests – books, music, sport, hiking, biking, food, friends, etc. – so I try to do a bit of it all. To be coordinated with the family, in particular, two kids who keep me happy and busy.

CC: Outside of the lab, I really enjoy canoeing on the Navigli, the famous canals in Milan. Being on the water allows me to slow down and take a break from the busy pace of the lab. I love the feeling of paddling along the canals, enjoying the surroundings and reconnecting with the city.

NP: Having grown up in Milan, I sincerely love this city and everything it offers. Outside of the lab, I like different things, from baking and crocheting to spending time with family and friends while enjoying the city’s cultural life, like its aperitivo culture and different neighborhoods. Recently, I also joined the Red Cross as a volunteer, where I am involved in social inclusion activities with homeless people, as well as assistance roles during public events. These experiences help me stay grounded, connected to the community and maintain balance alongside research.

RP: This job takes a lot of time and energy, but outside of the lab I really enjoy spending time with my family and friends. I also love fishing. I enjoy it for its unpredictability and complexity; it requires analyzing many variables and accepting failure without expectations. Every small decision can make a difference, and while nothing is guaranteed, everything is possible, like in science.

LNR: Outside of the lab, I enjoy traveling, reading, and all things food-related. In Milan, I particularly enjoy access to the ballet, opera, and theater.

DD: Outside of the lab, I really enjoy going for walks—especially in parks or outside the city, where I can reconnect with nature. Living in Milan, I also like going to the theater and meeting friends for an aperitivo.

BN: Outside the lab, I enjoy spending time reading, as it offers a break from continuous scientific reflection while still keeping my mind engaged in a pleasant way. I also like to take advantage of the many cultural and recreational initiatives that Milan has to offer, often in the company of my friends.

EM: I usually try to spend time in nature and clean air when I am not in the lab. Milano is really close to beautiful mountains and lake,s and those are my favorite spots for the weekend. I also enjoy food, art and history.

AG: In my free time, I enjoy reading and spending time in the mountains outside of Milan, whether it’s hiking, skiing or horseback riding. Skiing, in particular, is a great way to unwind on the weekends and enjoy the outdoors. Being able to combine outdoor activities with some quiet time to read makes my free time really enjoyable.

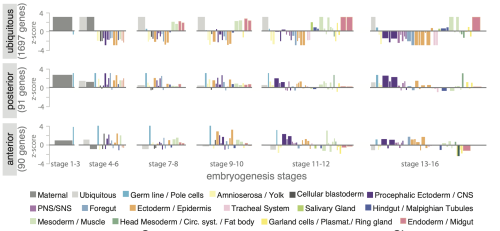

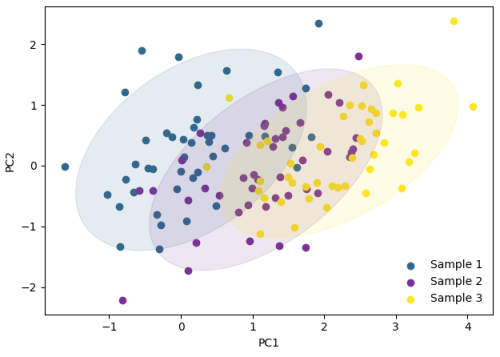

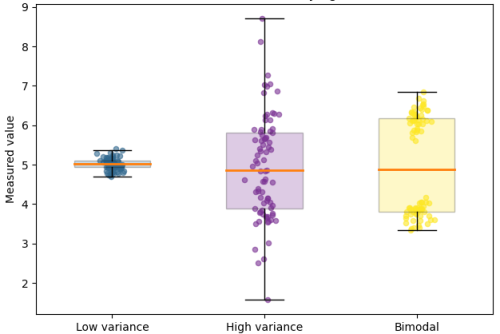

Posted by Helena Jambor, on 26 January 2026

or, Why all biologists needs data visualization

Biology probes form and function of Life. Form is easy to grasp: cells under a microscope, subcellular structures in electron micrographs, or organisms on camera readily present their shapes.

Function is different: it emerges from molecular compositions, interactions, and temporal changes. Such data is not directly visible – we use statistics to make sense of it.

But summaries and p-values alone rarely reveal how complex biological systems are organized, the variability in the samples and the resulting uncertainty in the data, or unexpected relationships and pattersn. As datasets grow larger and more complex, these insights only become accessible when data are visualized.

Despite being used widely, data visualization is still treated as a final step in research, a way to communicate results once the real analysis is finished. In reality, visualization plays a much earlier and more fundamental role. Visuals expose batch effects, hidden subpopulations, nonlinear behaviors, and experimental artifacts that often remain invisible to summary statistics alone. These insights directly shape which data can be trusted, which controls are needed, and which experiments should come next.

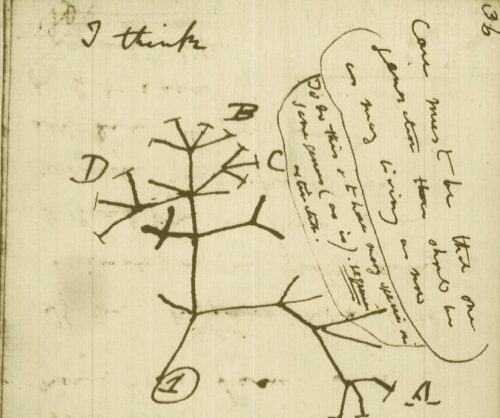

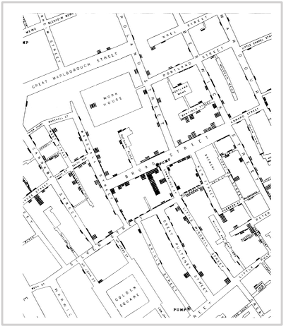

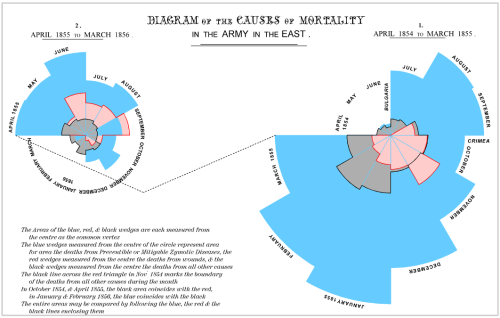

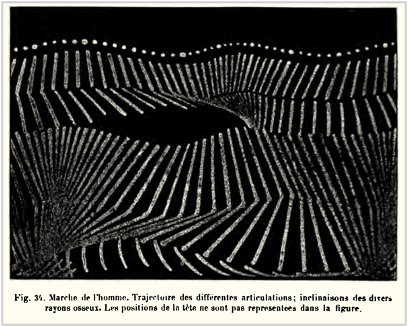

While the urgency to visualize data feels modern, the principle itself is not new. Seeing has always been central to biological understanding. Darwin’s and Linnaeus’s classification of species relied on careful visual comparison. In the nineteenth century, Florence Nightingale pioneered statistical charts to reform healthcare, while John Snow’s maps of cholera outbreaks transformed how disease transmission was understood. In the twentieth century, Michaelis and Menten introduced the kinetic plot as a standardized visual language for enzyme activity, and more recently, interactive genome browsers have made entire genomes navigable at nucleotide resolution.

Today, data visualization is however still poorly formalized in the life sciences. It lacks dedicated training programs, shared standards, and institutional recognition. This gap matters, as data visualization leads to hypotheses generation, insightful data presentation, and builds trust in the results.

Just as early scientists needed training in scientific drawing to accurately document what they observed, today’s researchers must learn to engineer and interpret data visualizations with comparable rigor. In an era where biology increasingly unfolds in data rather than images alone, learning how to see again has never been more important.

PS – I wrote this looking for discussions on this topic – feel free to reach out helena.jambor – at – fhgr.ch

Posted by Nivedita Mukherjee, on 21 January 2026

Reflections from a Workshop by Nivedita Mukherjee1 and Mateus de Oliveira Lisboa2

1National Centre for Biological Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, 560065, India (NCBS-TIFR)

2Core for Cell Technology, School of Medicine and Life Sciences, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR)

Last November, a unique gathering took place at Fanhams Hall in Hertfordshire, UK, for The Company of Biologists’ workshop titled “Decoding Whole Genome Doubling: Insights from Evolution, Development, and Disease.” Organised by Renata Basto and Zuzana Storchova, the workshop brought together a highly interdisciplinary cohort of scientists studying whole-genome doubling (WGD) across organisms, from flies and frogs to plants and humans.

As two of ten early-career researchers selected to participate, we had the rare opportunity to engage in close discussions with leaders in the field, present our own work, and explore the diverse biological contexts in which the entire chromosomal complement of a cell is doubled, changing its ploidy – the number of copies of the genome. Across three intense days, we uncovered how such changes can drive cellular adaptations, precipitate disease, and drive evolutionary innovation.

Ploidy variation is ubiquitous in biology. Even within a single organism, cells often carry different numbers of genome copies depending on the tissue type and developmental stage. For example, while humans are diploid as a species, polyploid cells are routine in organs such as the liver, heart and pancreas. These can arise from either programmed or accidental WGD, resulting from the skipping of one or more cell-cycle steps or through cell fusion. Once polyploidy arises, the cell is thrust into a new regime, one that demands extensive adaptation if it is to continue functioning or proliferating without compromising genome integrity.

Initial responses to genome doubling can be defensive. DNA damage and stress-response pathways are activated, and cell death is a common outcome unless these surveillance mechanisms are suppressed. Survival alone, however, is not enough. To continue to divide successfully, polyploid cells must carefully segregate their excess chromosomes. This often involves re-establishing functional mitotic spindles despite the presence of supernumerary centrosomes. Several talks highlighted molecular strategies that allow polyploid cells to survive and divide by rewiring apoptotic signalling and stabilising centrosome numbers.

Polyploid cells aren’t just more complex; they’re physically larger. This increase in volume comes with consequences: intracellular transport must traverse greater distances, metaphase spindles must span wider plates, and increased metabolic demands must be sustained. Several speakers described how these physicochemical constraints can be systematically probed using in silico models alongside in vitro perturbations.

Beyond these geometric and energetic challenges, it is tempting to assume that increased DNA content translates to increased gene expression. However, multiple presentations demonstrated that gene expression scales unevenly and nonlinearly with ploidy, with pronounced disparities between transcript abundance and protein yield. In some contexts, specific genes are selectively up- or down-regulated, rewiring the cell’s regulatory network in unexpected ways. This decoupling of genome content from functional output overturns the view of polyploid cells as merely “amplified” versions of their diploid counterparts.

For a cell, doubling its genome is not always a deliberate developmental strategy or a trivial bookkeeping error; it is often a high-risk gamble. Cardiomyocytes, for instance, become increasingly polyploid with age or heart disease, accompanied by a substantial accumulation of mutations. Whether polyploidy in such settings is adaptive, maladaptive, or merely tolerated remains an open question—one that echoes broader uncertainties about where normal physiology ends, and pathology begins.

Polyploidy-related genomic instability is also characteristic of cancer, with genome-doubled tumours showing many more chromosomal aberrations than diploid tumours. While high levels of such aberrations can be lethal, genome doubling also casts a paradoxical safety net by creating “genomic backups” that restore essential functions. At its extremes, WGD-induced genomic instability can be spectacular. One striking example is chromothripsis, where mis-segregated chromosomes trapped within micronuclei shatter and reassemble in chaotic ways, creating the genomic equivalent of a misassembled jigsaw puzzle.

A silver lining is that, while such drastic mutational events can accelerate cancer cell evolution, their dependence on these aberrant states may also be their undoing. Because WGD imposes unique cellular stresses, polyploid cancer cells acquire distinct vulnerabilities that may be therapeutically exploitable. The workshop highlighted several efforts to leverage these weaknesses, offering hope for selective treatments that preferentially target cancer cells while sparing normal tissue.

At the macro scale, genome doubling acts as a powerful driver of evolutionary change. Ancient WGDs have profoundly shaped the genomes of present-day microorganisms, plants, and vertebrates, with recent events producing drought-resistant plants, pest-resistant crops, and amphibians adapted to arid environments. Polyploid lineages often adapt rapidly, restructuring physiological and metabolic pathways, and frequently adopting self-pollination or asexual reproductive strategies to overcome early barriers to evolutionary establishment.

Across the tree of life, WGD is frequently followed by episodes of rapid diversification, though these bursts typically occur only after a delay. This “radiation lag” is thought to reflect the time required for re-diploidisation, during which redundant genomic content is reduced, and ohnologues or duplicated genes diverge in function. As gene dosage is re-balanced and new regulatory networks emerge, WGD becomes a springboard for long-term evolutionary innovation.

Such innovations may confer resilience during periods of ecological upheaval. Compelling evidence for this comes from the observation that WGD events in the evolutionary history of species are disproportionately clustered around major extinction events, such as the Cretaceous–Palaeogene boundary. Interestingly, environmental stressors, such as extreme heat or cold, can induce the formation of unreduced gametes, providing a direct link between ecological pressures and the origin of polyploid species.

Amid the breadth of scientific discussions at the workshop, one unifying theme stood out: WGD is neither an anomaly nor a biological accident. From plants surviving climate shifts to tumours evading physiological checks, genome doubling repeatedly emerges as a powerful strategy in life’s toolkit. Yet it remains a double-edged sword, capable of driving adaptation or unleashing instability.

This raises big questions. In healthy tissues, polyploidy seems to balance on a knife-edge between careful regulation and stochasticity. Understanding this balance could reveal why certain cells become polyploid, how tissues keep their abundance in check, and what stops them from turning cancerous. In cancer cells, it’s still unclear if WGD is a driving force or a downstream manifestation of genomic instability. Moreover, scientists are still figuring out how evolutionary pressures shape newly formed and established polyploid lineages, and how the opportunities for adaptation and diversification play out across different tissues and species.

What the field now needs is a shared language across disciplines. Polyploidy in microbes, plants, animals, cancer, and development has too often been studied in silos. By integrating these perspectives, we may finally decipher how a single genomic event reverberates from the scale of individual cells all the way to the evolution of multicellular species.

This workshop marked a step in that direction, and for us, a turning point in our understanding of what it means to live with, adapt to, and evolve through an extra genome.

Mateus de Oliveira Lisboa is a PhD student at the Core for Cell Technology, PUCPR (Brazil), studying how whole-genome doubling shapes cell fate, evolution, and disease. With a background in chromosome biology, stem cells, and the cancer microenvironment, he integrates molecular biology and bioinformatics to explore the causes and consequences of large-scale genomic alterations, always through an evolutionary lens. Outside the lab, he explores mountains, photography, astronomy, and birds.

Nivedita Mukherjee is a PhD student at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS–TIFR), Bengaluru, India, where she studies cancer evolution through the computational analysis of large-scale genomics datasets. Her research integrates statistical genomics and evolutionary theory to examine how whole-genome doubling reshapes selective pressures in cancer. Beyond research, Nivedita writes popular science articles and enjoys singing, travelling, photography, and reading.

Posted by the Node, on 20 January 2026

[Editorial from Development by James Briscoe, Swathi Arur, Anna Bigas, Dominique Bergmann, Benoit G. Bruneau, Cassandra G. Extavour, Paul François, Anna-Katerina Hadjantonakis, Haruhiko Koseki, Thomas Lecuit, Matthias Lutolf, Irene Miguel-Aliaga, Samantha A. Morris, Kenneth D. Poss, Elizabeth J. Robertson, Peter Rugg-Gunn, Debra L. Silver, James M. A. Turner, James M. Wells, Steve Wilson.]

Every researcher knows the anticipation and trepidation that come with submitting a paper to a journal. Years of effort have been distilled into a few thousand words and a handful of figures containing the metaphorical (and often literal) sweat from long hours and hard toil in the lab. What will the reviewers say? How will the editor deal with it? At Development, we understand the anxiety and the investment that goes with a paper submission. Our mission is to provide the kind of expert, constructive review that not only evaluates your work but helps it achieve its full potential for lasting scientific impact. But we know that the comments provided by reviewers don’t always live up to this expectation. We’ve heard the concerns. Some of these frustrations reflect deeper, systemic issues across scientific publishing: the feeling that revision requests can expand beyond what is feasible, that editorial decisions are not always transparent, and that standards can seem uneven across subfields such as developmental and stem cell biology. These are not challenges unique to Development, but we acknowledge them and continue to refine our editorial practices to address them wherever possible.

We’ve been told that Development is ‘too hard to publish in’, that reviews are unnecessarily harsh, that revisions are excessive and time-consuming. These criticisms matter to us. Even though sometimes it might be more perception than reality, we won’t pretend that there isn’t some truth in these criticisms. As active research scientists ourselves, we Editors face similar frustrations with our own papers. We want to be transparent about Development’s reviewing process and explain how we endeavour to get the balance right so that it serves both authors and the scientific community.

First, the numbers behind the perception. The bottom line is that, for the past 10 years, 35-45% of papers submitted to Development ultimately get published. Let us break this down. Roughly 65% of the manuscripts submitted to Development are sent out for peer review. We only editorially reject papers when the topic of the article is beyond our scope and expertise, or it is clear to us that the study would not be supported by our peer reviewers. A rapid rejection allows authors to quickly redirect their manuscript to more appropriate venues and, where relevant, we facilitate direct transfers to our sister journal, Biology Open. Of the papers we send for peer review, well over 50% receive positive reviews from reviewers and we ask the authors to revise and resubmit these…