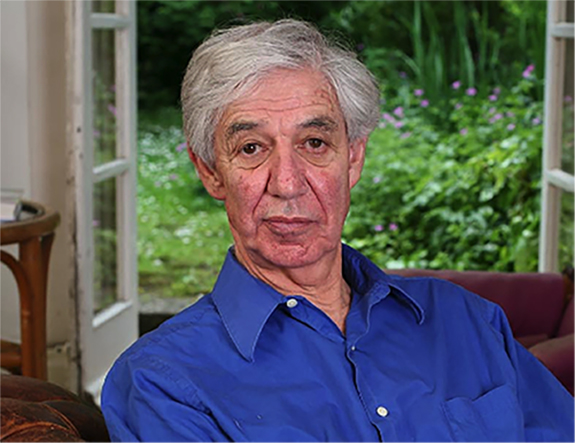

An interview with Lewis Wolpert

Posted by the Node, on 4 August 2015

This interview first featured in Development.

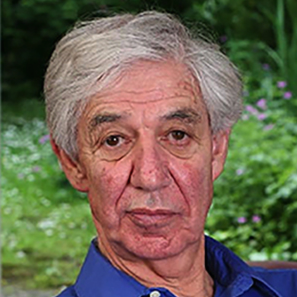

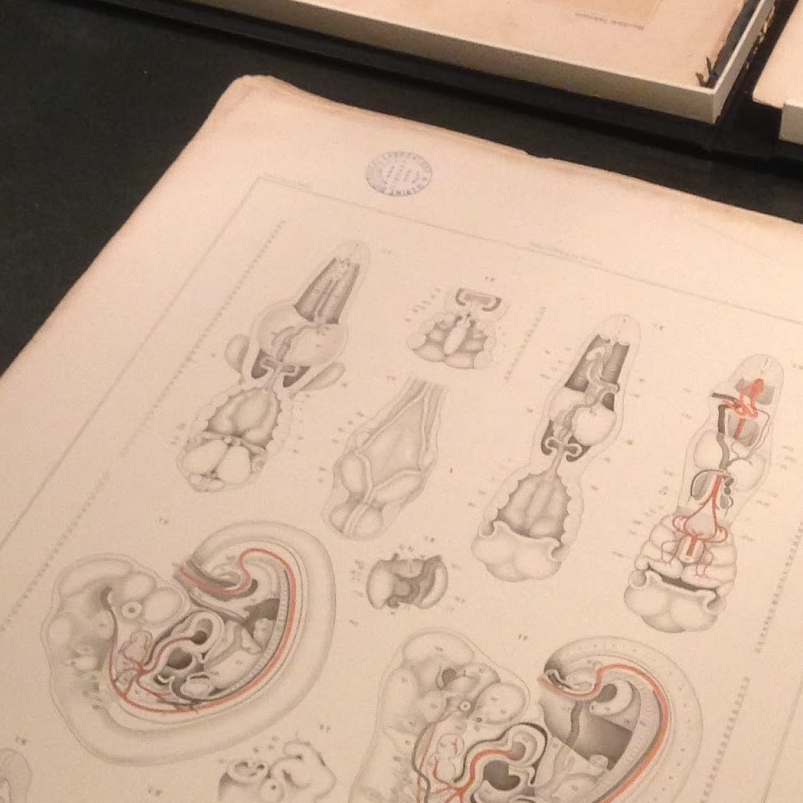

Lewis Wolpert is a retired developmental biologist who, over his long career, has made many important contributions to the field, from his French Flag model and the concept of positional information to the famous quote that it is “not birth, marriage or death, but gastrulation which is truly the most important time in your life.” In addition to his scientific contributions, Lewis is also a prolific writer, from the textbook ‘Developmental Biology’ to books about popular science, religion and his battle with depression. Although born in South Africa, it was in the United Kingdom that Lewis spent most of his scientific career. We met Lewis at the Spring Meeting of the British Society for Developmental Biology, where he was awarded the Waddington Medal.

What does it mean to you to receive the Waddington Medal?

What does it mean to you to receive the Waddington Medal?

It is wonderful. I was very excited indeed to receive it. I knew Conrad Waddington, who was a friend of mine, so it makes it personal. And of course I am a developmental biologist and I am old, so it is very nice to receive it!

This award recognises your career contributions to developmental biology, but you were originally a civil engineer. How did you make this transition?

I studied civil engineering during my undergraduate studies because I wanted to do science. I qualified as a civil engineer, and worked as a soil mechanic for a building research institute for two years. However, I had been involved with Mandela and was a bit frightened, so I decided to leave South Africa to get away from the politics…and also from my parents! I hitchhiked up Africa and eventually ended up in Europe. I did another course in soil mechanics at Imperial College but was very unhappy: I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life working on soil mechanics! A friend of mine knew this, and he had read some papers where people were looking at the mechanics of cell division. So I went to King’s College in London where I did a PhD on this topic. Having a civil engineering background gave me a very different perspective, and I applied my mechanics knowledge to the cells. And this is how I got involved in biology.

You have switched fields and models multiple times in your career – from cell mechanics to developmental biology, from sea urchins and amoebae to Hydra and the vertebrate limb. What motivated these changes and how easy was it to make these moves?

I did my cell mechanics PhD mainly on sea urchin eggs. I became interested in sea urchin development, and that’s how I got into developmental biology. However, to work on sea urchins you needed to visit marine stations and this became difficult once I got married. I therefore switched to working on Hydra for a time. Later, I moved to Middlesex Hospital Medical School, now part of University College, London, and I felt that Hydra was not an appropriate model to work on in a medical school. So I started working on the development of the limb. Changing so many times, from civil engineering to biology and then to different systems, required me to work very hard. For example, during my PhD I had to learn quite a lot and pass exams in zoology. It was a little difficult but interesting.

You’re perhaps best known for your French Flag model of positional information. This is now considered a landmark publication but wasn’t widely accepted at first. Why do you think that was?

Conrad Waddington had organised a theoretical biology meeting at Serbelloni, on Lake Como in Italy, and the idea was well received there. However, when I gave a big lecture on it at Woods Hole nobody would speak to me afterwards. I don’t know what it was, but the Americans didn’t like my ideas. The next morning, while I was bathing, Sydney Brenner found me crying in the water and said “Lewis, pay no attention. We like your ideas. Pay no attention to people who don’t like it.” And he’s the one who saved me. He gave me total encouragement, so I didn’t care that all these Americans didn’t like what I was doing. If Sydney liked it, that’s what mattered, because Sydney is an amazing man. I knew him from South Africa of course, since I went to university with him. He is funny and brilliant, the only genius I know. And Francis Crick liked my ideas too. So that lecture was a bit of a disaster but I recovered because of Sydney. It took quite a long time for the Americans to come around and accept my ideas.

It’s now over 45 years since you proposed this model. Where do you think the French Flag model fits with our current understanding of positional information, and what do you think are the exciting questions at the moment?

There are problems we haven’t solved. It is terrible, but we still don’t have a molecular basis for it. If I still had an active lab, finding the molecular basis for positional information would be my objective, but would be quite tricky, since I’m not a biochemist or molecular biologist. There is one case of a molecule that might encode positional information, Prod 1, which is graded along the amphibian limb and was discovered by Jeremy Brockes. But it would be nice to find similar molecules in other systems.

You have said in earlier interviews that you are not interested in the details, but rather in the overall principles, and also that you don’t like doing experiments. How has this influenced your career?

I’m really a theoretician – I’m not very good at doing experiments! Fortunately I had PhD students, postdocs and research workers to do the experiments for me. I had, for example, a German technician, Amata Hornbruch, who was my hands for 20 or 30 years!

Over the years many of your PhD students and postdocs moved on to become successful developmental biologists in their own right – including previous winners of the Waddington Medal, Julian Lewis and Jim Smith. Are you proud of your mentoring?

Absolutely. I was very fortunate to work with very nice people. I’m very pleased with them – I like them very much and we got on very well. I encouraged them, and we had good discussions. It is very satisfying to see them doing well.

How do you think science has changed since your early days, and do you have any advice for young scientists?

Oh, it has changed tremendously. I would always say “don’t be frightened of changing your career as a scientist.” It is hard for young scientists to know what they should work on. When I look at journals these days I find them very boring. It’s just detail and very little general theory at all. Find something really exciting and don’t be afraid. If you are going to spend your life just studying little details it won’t be terribly interesting. At least for me! Study something like the brain, where we understand the least. It is a very exciting and complicated area.

Over the years you have written several popular science books, presented the RI Christmas Lectures and have generally been an advocate for science education. Do you consider yourself passionate about science outreach? Do you encourage other scientists to communicate their science?

I would, but it’s not terribly rewarding. Rather, it is quite rewarding and I enjoyed it, but I don’t think people pay much attention! I was quite involved in outreach because I was the Royal Society chairman of the committee for the public understanding of science, but I don’t think we made much progress. And I wrote a textbook, of course. Funnily enough I’m just writing a book at the moment, asking ‘What has science done for us?’ It addresses the way science has affected our lives, not just from a biology perspective but also physics, chemistry, the lot.

You have been very open about your battles with depression. What advice would you give to young scientists struggling with mental health issues?

They should be open about it and try to get cognitive therapy. I found professional therapy very helpful. You know, when I came out of my depression, out of hospital – I was in hospital for three weeks – my wife hadn’t told anybody that I was depressed. She just said that “he’s very tired and not feeling well.” The stigma related to depression is still very severe and that makes it much worse. That’s why I wrote a book about it. I wanted to understand what depression was, so I researched it a bit. I still lecture on depression every now and then. In fact I’m shortly going to Abu Dhabi to give a lecture on depression.

What would people be surprised to find out about you?

Just how bad my memory is! My favourite story is that I was once in my son’s house in Cambridge, and they were away. I went downstairs for breakfast and I found a young woman in the kitchen, doing some washing up. I said, “Hello, and where are you from?” It was my granddaughter! I didn’t recognise her!

(20 votes)

(20 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(3 votes)

(3 votes)