This obituary first appeared in Development.

Paul Martin and David Ish-Horowicz look back on the life and work of their long-time friend and colleague Julian Lewis, who passed away on April 30th 2014.

Julian Lewis made unique contributions to several areas of cell, developmental and theoretical biology. He combined a formidable intellect and mathematical training with experimental dexterity and deep biological insight, and used these to great effect to study key questions in early embryonic patterning, neurogenesis and, most recently, Notch signalling and somitogenesis. His fluent prose was evident in his publications and also in the textbook Molecular Biology of the Cell, to which he was a major, founding contributor. His kindness and gentleness endeared him to all, especially to the many people whom he mentored as they passed through his lab. He inspired them and his numerous collaborators and colleagues, all of whom will be bereft at the loss of an irreplaceable colleague.

Julian Lewis made unique contributions to several areas of cell, developmental and theoretical biology. He combined a formidable intellect and mathematical training with experimental dexterity and deep biological insight, and used these to great effect to study key questions in early embryonic patterning, neurogenesis and, most recently, Notch signalling and somitogenesis. His fluent prose was evident in his publications and also in the textbook Molecular Biology of the Cell, to which he was a major, founding contributor. His kindness and gentleness endeared him to all, especially to the many people whom he mentored as they passed through his lab. He inspired them and his numerous collaborators and colleagues, all of whom will be bereft at the loss of an irreplaceable colleague.

Julian grew up in West London, attending St Paul’s School, where he was an outstanding linguist. He studied physics at Oxford University, remaining there for his DPhil in theoretical physics. He then spent eighteen months as a postdoc at the Institute for Physical Problems in Moscow, helped by his fluent spoken and written Russian – just one of his non-English languages.

Julian’s long-standing fascination with natural history led him to accept a postdoc position in Lewis Wolpert’s lab at the Middlesex Hospital, which soon became the epicentre of studies on chick limb patterning – the system that triggered many influential theories of vertebrate embryonic patterning that we now take for granted. Julian began working closely with Denis Summerbell, a doctoral student in the lab and, together, they provided the theoretical and experimental basis for the progress zone model of limb patterning, which still influences our ideas of how spatial organisation arises during vertebrate development (Summerbell et al., 1973).

Other colleagues in the Wolpert lab at the time included Jonathan Slack, Cheryl Tickle, Jim Smith and Nigel Holder. This team unearthed many important mechanistic insights from cut-and-paste surgical experiments, thereby laying the foundation for subsequent molecular advances in understanding limb patterning. Julian’s big contributions were in figuring out how cells in the progress zone might measure ‘time’, and how this in turn imparts proximodistal positional values on cells. Several papers involved a combination of experimental and mathematical analysis; they included Julian’s first exploration of how timing mechanisms might pattern tissues – a much understudied problem at the time.

In 1978, Julian set up his own lab at the Anatomy Department of King’s College, London on the Strand,where he taught histology, with a healthy dose of cell biology, and also met his American future-wife Sherry, who was in London doing a PhD in neuroanatomy. His lab there began to examine how the various tissue components of the limb – skeletal elements, muscles, nerves and blood vessels – arrange themselves appropriately in relation to one another. The experiments revealed a hierarchy of interactions such that, for example, connective tissue defined ‘trunk roads’ taken by all limb nerves, which then followed individual paths in response to chemoattractants released by skin or muscle targets (Lewis et al., 1981).

While still at King’s, Julian and his postdoc Gavin Swanson switched models and began to study development of the otic vesicle, which gives rise to the sensory epithelium of the inner ear. One transition paper had them peeling open the otic vesicle and grafting it onto a host chick limb bud, where it differentiated to form the exquisite normal patterning of hair cells, making the process accessible to experimental manipulation (Swanson et al., 1990). Julian’s innovative idea of injecting white paint into the ear to visualise its morphology was a further example of his ingenuity.

In 1986, Julian jumped at an offer to move his lab to the new Imperial CancerResearch Fund (ICRF) Developmental Biology Unit, which had just been set up in Oxford under the directorship of Richard Gardner. Here was a thriving community of interactive groups with most of the major model systems represented along a compact floor at the top of the Zoology Building: flies (Ish-Horowicz and Ingham), chick (Lewis), frogs (Slack), mice (Gardner, Copp and Beddington) and, later, zebrafish (Ingham). These were very exciting times in developmental biology, as striped gene expression patterns in Drosophila competed with new mesoderm-inducing factors in Xenopus for pages in Nature. Julian’s interactions with everyone in the Unit were key to its success and to that of its students and postdocs.

Julian’s major interest remained the inner ear, and he uncovered clues about its morphogenesis, the inductive signals that kick-start its invagination from head ectoderm and how the semicircular canals are formed. He also made a foray into wound healing; in the early 1990s, he published a paper showing that wounds in the simple embryonic epidermis closed by means of an actomyosin cable that assembled in the leading edge cells (Martin and Lewis, 1992). This cable turned out to be a general feature of wound healing in many systems, and is also present during normal morphogenesis, e.g. during dorsal closure in fly embryos.

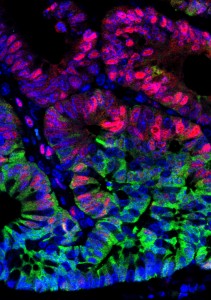

Julian also became increasingly fascinated by the problem of how local patterning was established in the otic epithelium; in particular, with the beautiful hexagonal arrays of individual hair cells, each hair being surrounded by separating support cells. This patterning smelled of ‘lateral inhibition’, the process mediated by Delta-Notch signalling that had been shown to generate regularly spaced neural precursors in Drosophila – an idea that led him to embark on a series of landmark studies of Notch signalling in vertebrates.

In collaborationwith the Ish-Horowicz lab down the corridor and the Kintner lab in San Diego, Julian’s team showed using Xenopus and chick that a cell’s decision whether to become neural is indeed regulated by Delta-Notch signalling and lateral inhibition – individual differentiating neural cells express the ligand Delta, which inhibits direct neighbours from also differentiating and preserves them as progenitor cells (Henrique et al.,1995; Chitnis et al., 1995). Subsequent work in the chick retina confirmed this model, showing that Delta- Notch signalling regulates the timing and progression of differentiation, but not the type of neuron formed (Henrique et al., 1997).

The Oxford Unit was closed in 1996, and several groups, including the Ish-Horowicz and Lewis labs, transferred to the main ICRF (now Cancer Research UK) institute at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London. There, Julian began to switch his research to zebrafish, taking advantage of its genetics and suitability for advanced microscopy (the physics of which he understood well) to study the molecular processes involved in cell fate diversification in vivo.

The Delta-Notch story continued with studies of its role in patterning in the developing zebrafish gut and vasculature, but Julian also began a series of incisive experiments on vertebrate segmentation, studying in particular how the regular production of somites (the precursors of our axial skeleton and muscles) is controlled by a molecular oscillator (‘clock’). Here too, he showed that Notch signalling was crucial, acting to synchronise the clocks of neighbouring cells (Jiang et al., 2000). Equally ground-breaking, he modelled the zebrafish clock as a simple, delayed negative-feedback loop based on transcriptional autorepression. He showed that the period of such a clock would depend on the kinetics of synthesis and breakdown of the mRNAs and proteins of the clock, rather than on their absolute protein concentrations (Lewis, 2003). Crucially, he showed that noise in the circuit, far from disrupting the oscillations, contributes to the circuit’s robustness. This single-author paper has formed the basis for most of the subsequent work in the field.

For his collective work, Julian was awarded the British Society of Developmental Biology’s highest accolade, the Waddington Medal, in 2003, and was elected to EMBO membership in 2005 and as a Fellow of The Royal Society (FRS) in 2012. He closed his lab in 2012 but continued working; his most recent paper was published this April in Development (Soza-Ried et al., 2014) and was a perfect example of what the funders now call ‘predictive science’. His lab showed that the development of normally sized somites could be rescued in embryos lacking endogenous Delta expression by delivering regular pulses of Delta activity, thereby confirming his mathematical prediction of Notch-mediated clock synchronisation. It was particularly appropriate that this last paper was published in Development – his 24th in this journal (and its predecessor, JEEM) – on whose editorial board he served between 1988 and 1998.

Julian was a wonderful mentor who gently nudged the best out of all of his graduate students and postdocs, showing immense patience with those of us who were slower than he was in grasping inferences, concepts and equations. He wrote beautifully; his prose was almost lyrical, as if it had been ‘sprinkled with magic’ as described by one journal editor.

For the last ten years of his life Julian suffered from prostate cancer, which led to his making an important contribution to the cancer research community. He talked widely on the biology and treatment of cancers to general scientific and lay audiences. These were especially powerful and important talks; near the end of each, he would show data from a drug trial (Fong et al., 2009) and a bone scan showing metastases, at which point he indicated that he himself was a participant in the trial and that the bone scan and metastases were his. The bravery of a patient advocate talking so lucidly and in such clear scientific language about his personal experience taking a novel cancer drug had tremendous scientific and emotive impact. His tremendous courage and stoicism were also evident in his continued productivity despite his pain and discomfort. In the weeks before he died, Julian also delivered final drafts of two of his chapters for the 6th edition of Molecular Biology of the Cell, as well as a new section on computational biology.

Julian was a scientist’s scientist, with a legendary ability to ask the gentle ‘killer’ question at a seminar despite sleeping through most of it. He could be slightly ‘over the top’ on matters of clarity and precision, once walking out of a seminar to check a controversial but critical fact from a journal article in the library – and he was the speaker! He also had an idiosyncratic dress style, classifying his sweaters into two categories: ‘with holes’ and ‘without holes’. But he was also a lovely human being and a ‘renaissance man’ whose wide interests incorporated music, artistic prints, ceramics (which both he and Sherry collected avidly) and second-hand books, which were usually read in the original Russian or French. He was a devoted husband and father – with Sherry he raised three science-orientated daughters. He is sorely missed by them, and by all of us who knew and loved him.

References:

Chitnis, A., Henrique, D., Lewis, J., Ish-Horowicz, D. and Kintner, C. (1995). Primary neurogenesis in Xenopus embryos regulated by a homologue of the Drosophila neurogenic gene Delta. Nature 375, 761-766.

Fong, P. C., Boss, D. S., Yap, T. A., Tutt, A., Wu, P., Mergui-Roelvink, M.,Mortimer, P., Swaisland, H., Lau, A., O’Connor, M. J. et al. (2009). Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 123-134.

Henrique, D., Adam, J., Myat, A., Chitnis, A., Lewis, J. and Ish-Horowicz, D.(1995). Expression of a Delta homologue in prospective neurons in the chick. Nature 375, 787-790.

Henrique, D., Hirsinger, E., Adam, J., Le Roux, I., Pourquié, O., Ish-Horowicz, D. and Lewis, J. (1997). Maintenance of neuroepithelial progenitor cells by Delta- Notch signalling in the embryonic chick retina. Curr. Biol. 7, 661-670.

Jiang, Y.-J., Aerne, B. L.,Smithers, L., Haddon, C., Ish-Horowicz, D. and Lewis, J. (2000). Notch signalling and the synchronisation of the somite segmentation clock. Nature 408, 475-479.

Lewis, J. (2003). Autoinhibition with transcriptional delay. A simple mechanism for the zebrafish somitogenesis oscillator. Curr. Biol. 13, 1398-1408.

Lewis, J.,Chevallier, A., Kieny, M. and Wolpert, L. (1981). Muscle nerve branches do not develop in chick wings devoid of muscle. J.Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 64, 211-232.

Martin, P. and Lewis, J. (1992). Actin cables and epidermal movement in embryonic wound healing. Nature 360, 179-183.

Soza-Ried, C.,Ö ztü rk, E., Ish-Horowicz, D. and Lewis, J. (2014). Pulses of Notch activation synchronise oscillating somite cells and entrain the zebrafish segmentation clock. Development 141, 1780-1788.

Summerbell, D., Lewis, J. H. and Wolpert, L. (1973). Positional information in chick limb morphogenesis. Nature 244, 492-496.

Swanson, G. J., Howard, M. and Lewis, J. (1990). Epithelial autonomy in the development of the inner ear of a bird embryo. Dev. Biol. 137, 243-257.

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series

In zebrafish, the circadian clock, which is the internal timekeeper that coordinates multiple cellular, physiological and behavioural processes with the external rhythmic environment, begins cycling very early in development. However, the functional relevance for embryonic and larval development of these early circadian oscillations is unclear. Here (p.

In zebrafish, the circadian clock, which is the internal timekeeper that coordinates multiple cellular, physiological and behavioural processes with the external rhythmic environment, begins cycling very early in development. However, the functional relevance for embryonic and larval development of these early circadian oscillations is unclear. Here (p.  A key question in developmental biology is how different tissues maintain proportional growth during development. A striking example of this is the tiling of sensory dendrites across the body wall of theDrosophila larva: during early larval life, the neuronal dendrites extend to cover the entire body wall, without overlapping. As the larva grows further, tiling is maintained – meaning that the dendrites and the overlying epithelium grow proportionally (dendrite-substrate coupling). On p.

A key question in developmental biology is how different tissues maintain proportional growth during development. A striking example of this is the tiling of sensory dendrites across the body wall of theDrosophila larva: during early larval life, the neuronal dendrites extend to cover the entire body wall, without overlapping. As the larva grows further, tiling is maintained – meaning that the dendrites and the overlying epithelium grow proportionally (dendrite-substrate coupling). On p.  The shoot apical meristem (SAM) is the growing tip of the plant stem, from which a population of pluripotent stem cells generates all above-ground organs. The SAM is organised both in a central-to-peripheral manner, with the central zone containing the stem cells while their progeny differentiate in the peripheral zone, and in outer-to-inner layers that generate different cell types. These different zones and layers of the SAM are presumably defined and regulated by distinct (if overlapping) gene regulatory networks, and G. Venugopala Reddy and co-workers (p.

The shoot apical meristem (SAM) is the growing tip of the plant stem, from which a population of pluripotent stem cells generates all above-ground organs. The SAM is organised both in a central-to-peripheral manner, with the central zone containing the stem cells while their progeny differentiate in the peripheral zone, and in outer-to-inner layers that generate different cell types. These different zones and layers of the SAM are presumably defined and regulated by distinct (if overlapping) gene regulatory networks, and G. Venugopala Reddy and co-workers (p.  DNA and histone methylation patterns correlate with – and define – transcriptional activity of the genome. In particular, DNA hypomethylation is associated with active chromatin and generally thought to be permissive for gene transcription. However, this rule is not globally applicable, and Shinichi Morishita, Hiroyuki Takeda and colleagues (p.

DNA and histone methylation patterns correlate with – and define – transcriptional activity of the genome. In particular, DNA hypomethylation is associated with active chromatin and generally thought to be permissive for gene transcription. However, this rule is not globally applicable, and Shinichi Morishita, Hiroyuki Takeda and colleagues (p.  Interest in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) has increased in recent years due to its involvement in Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding the basic biology of APP and its physiological role during development thus will provide a better comprehension of Alzheimer’s disease.

Interest in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) has increased in recent years due to its involvement in Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding the basic biology of APP and its physiological role during development thus will provide a better comprehension of Alzheimer’s disease.  Multicellular rosettes have recently been appreciated as important cellular intermediates that are observed during the formation of diverse organ systems. Here, Nechiporuk and colleagues review recent studies of the genetic regulation and cellular transitions involved in rosette formation. They discuss and compare specific models for rosette formation and highlight outstanding questions in the field. See the Review on p.

Multicellular rosettes have recently been appreciated as important cellular intermediates that are observed during the formation of diverse organ systems. Here, Nechiporuk and colleagues review recent studies of the genetic regulation and cellular transitions involved in rosette formation. They discuss and compare specific models for rosette formation and highlight outstanding questions in the field. See the Review on p.  The epidermis is an integral part of our largest organ, the skin, and protects us against the hostile environment. Here, Jensen and co-workers discuss stem cell behaviour during normal tissue homeostasis, regeneration and disease within the pilosebaceous unit, an integral structure of the epidermis that is responsible for hair growth and lubrication of the epithelium. See the Review on p.

The epidermis is an integral part of our largest organ, the skin, and protects us against the hostile environment. Here, Jensen and co-workers discuss stem cell behaviour during normal tissue homeostasis, regeneration and disease within the pilosebaceous unit, an integral structure of the epidermis that is responsible for hair growth and lubrication of the epithelium. See the Review on p.