This article was first published in Development, and was written by Timothy T. Weil, Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge.

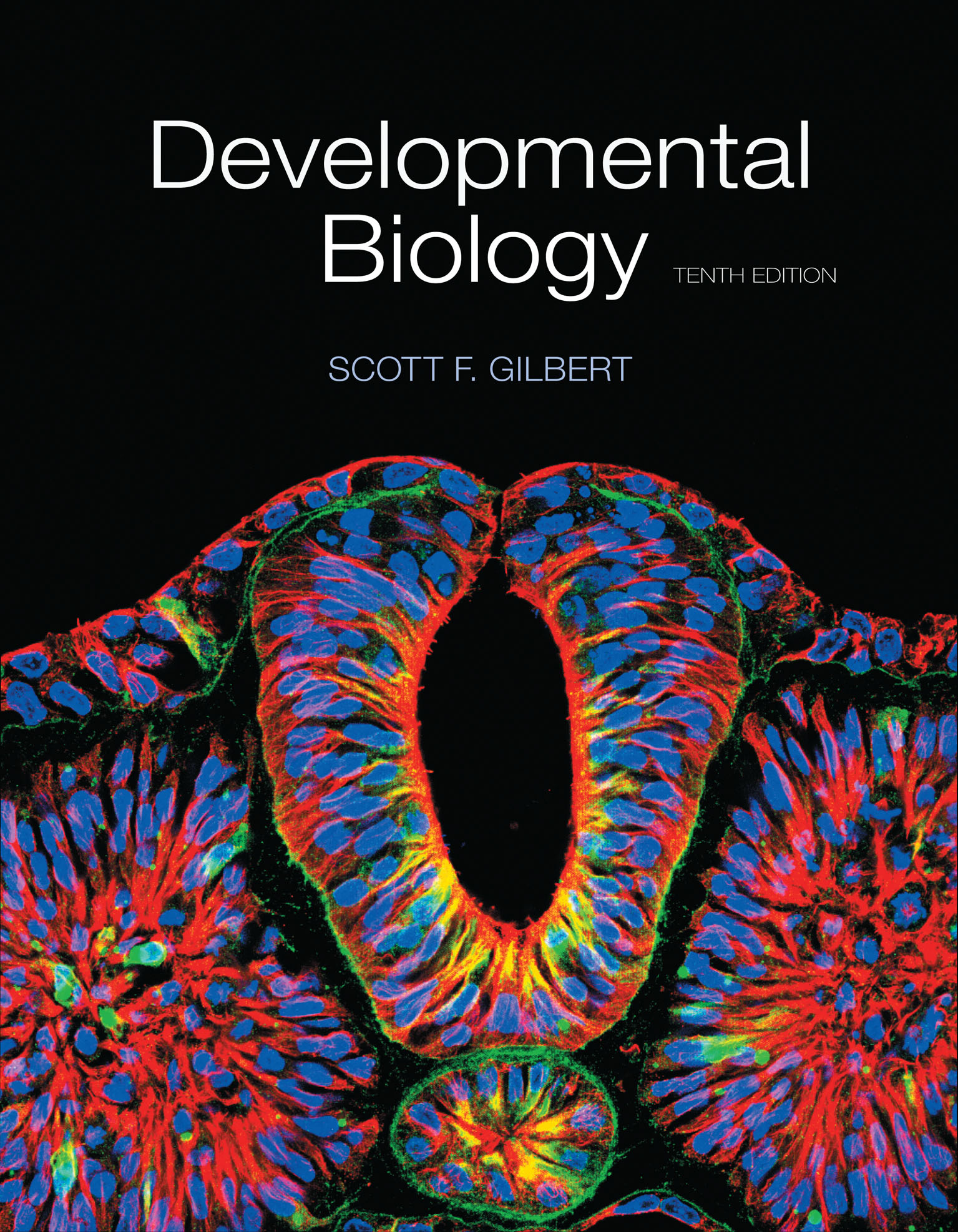

In the age of Google and Wikipedia, what is the role of the textbook? When revising lecture notes, what motivates a student to pull a clunky book off the shelf, rather than hitting the keyboard and accessing millions of search results in tenths of a second? The question for today’s educator might actually be how to steer undergraduates to the best-suited, most applicable source. When teaching developmental biology, the 10th edition of Developmental Biology by Scott F. Gilbert provides an elegant solution to this conundrum.

In the age of Google and Wikipedia, what is the role of the textbook? When revising lecture notes, what motivates a student to pull a clunky book off the shelf, rather than hitting the keyboard and accessing millions of search results in tenths of a second? The question for today’s educator might actually be how to steer undergraduates to the best-suited, most applicable source. When teaching developmental biology, the 10th edition of Developmental Biology by Scott F. Gilbert provides an elegant solution to this conundrum.

Any text in its 10th edition is likely to have had a great deal of success, and Gilbert is no different. The work is comprehensive, with all the expert detail and beautiful data that have become synonymous with his book. While online searches and primary articles can be very intimidating to students and often compound pre-existing confusion, Gilbert works well as an entry point into the vast literature on all the topics covered. The text can function both as a general tool that can be read chapter by chapter, and as a reference for specific questions. This dependable and friendly text enables students to acquire quality basic information, and subsequently directs them smoothly to the primary literature for further exploration.

Like a prologue to a play, the first pages of the text set the scene and introduce the main characters, relationships and drama that motivate the action to follow. Gilbert’s 10th edition is presented in four parts: Questions, Specification, The Stem Cell Concept and Systems Biology. This structure remains mostly unchanged from the previous version; a pragmatic reorganisation that was introduced between the 8th and 9th editions. Each part opens with an introduction in review-like style and standard. These prefaces work well, placing the information to be presented in context, as well as informing and exciting the reader as to why it is important.

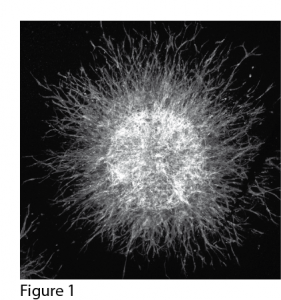

The book is further divided into 20 chapters that are well organised, easy to navigate, comprehensive and enriched with primary images and effective diagrams (an impressive 694 illustrations in 719 pages). Within the four parts, the chapters are linked with short, concept-driven openings and end with concluding remarks in the ‘coda’ section, creating a cohesive quality to the book. Also included at the end of each chapter is a ‘snapshot summary’, suggestions for further reading and directions to the online resources that are provided as part of the book package. Although these are expected components of any top textbook, Gilbert executes them extremely well. Throughout the chapters, there are stand-alone sections entitled ‘Sidelights & Speculations’, such as ‘The Nonequivalence of Mammalian Pronuclei’, ‘BMP4 and Geoffroy’s Lobster’ and ‘Transposable DNA Elements and the Origins of Pregnancy’. These vignettes have a mini-review quality to them and are good launch points for small group discussions.

Notably, the 10th edition has considerable new content and references, helping to maintain its position at the leading edge of available textbooks. This includes, but is by no means limited to, content on microRNA-mediated gene silencing, a new Crepidula (sea snail) fate map, epigenetic mechanisms of X inactivation, new ideas of neural tube closure, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions in cancer and developmental plasticity due to climate change.

For undergraduate course designers and lecturers, it is useful that the text is question driven, and includes many techniques ranging from classical transplantation and genetic screens to modern molecular networks and super-resolution microscopy. This provides the reader with the necessary information to think about the data as the original researcher did – an essential component in the education of young scientists.

Inherently, however, a textbook is out of date as soon as ink hits paper. It is therefore unfair to criticise the book on failing to include recent advancements, such as the CRISPR/Cas technology for genome engineering in Drosophila and other species. However, these limitations must be noted when considering the place of textbooks, as education inexorably moves towards a paperless existence.

The book ‘extras’ are an attempt to bridge the gap between paper and screen. These include the companion website www.devbio.com – self-described as a ‘museum’ with different ‘exhibits’ that ‘enrich courses in developmental biology’ – and vade macum3, a ‘laboratory manual’ that ‘helps students to understand the organisms discussed and prepare for the laboratory’. Both supplement the text, but are not essential to the book experience. They seek to provide an interactive avenue for students to explore, but when competing against the web are unlikely to become the first point of call for a student. However, they do offer an additional resource for instructors to enhance their lecture material with some available images and short videos. Moreover, by contacting the publisher, lecturers who confirm adoption of the text as part of their course may be granted access to ‘The Instructor’s Resource Library’. This includes images and presentation documents of all figures, tables and videos found in the text. This is a windfall for new lecturers and established educators looking to refresh their material.

Beyond the scientific realm, the text displays Gilbert’s ability to wear other literary hats, keeping the reader interested and engaged. He acts as historian as he brings alive the rich tapestry of developmental biology research; as columnist when relating the science to cultural quotes from the likes of T. S. Eliot, Steve Jobs, Emily Dickinson and Frank Lloyd Wright to name but a few; and finally as comedian with a lighthearted section on the website including ditties such as ‘The Histone Song’, links to YouTube videos and amusing articles.

Altogether, Developmental Biology by Gilbert is a classic and fundamental text. At £52.99 (RRP €63.58, $139.95), it is worth considering whether the 10th edition is a necessary upgrade. For general biology students, older editions will likely suffice. For lecturers or aficionados, the new content is nice, but not essential, especially for anyone owning the 9th edition. However, if you want an excellent text for teaching and learning developmental biology, the 10th edition is an ideal resource.

In the social media-dominated world of today, the future of the traditional course textbook is uncertain. The prospect of a continuously updated, interactive online ‘book’, complete with embedded links to primary sources, live movies and interactive images, is appealing. Still, at present there is no substitute for the well-written, accurate and engaging reference book exemplified by the 10th edition of Developmental Biology by Gilbert.

Developmental Biology, 10th edition by Scott F. Gilbert. Sinauer Associates (2013), 750 pages. ISBN: 9780878939787. $139.95 (hardback).

International Edition: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN: 9781605351735. £52.99, €63.58.

(7 votes)

(7 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

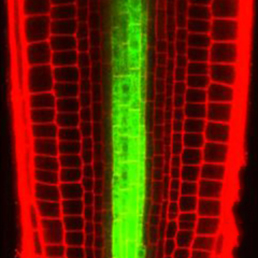

In the Arabidopsis root, xylem is organised into a central file of metaxylem that is flanked by protoxylem. Xylem fate is determined by HD-ZIP III transcription factors; high levels promote metaxylem formation whereas low levels specify protoxylem. The factors that downregulate HD-ZIP III levels are known but those that promote HD-ZIP III expression have remained elusive. Yunde Zhao, Ykä Helariutta, Jan Dettmer and colleagues now show that auxin biosynthesis promotes HD-ZIP III expression and metaxylem specification in Arabidopsis (

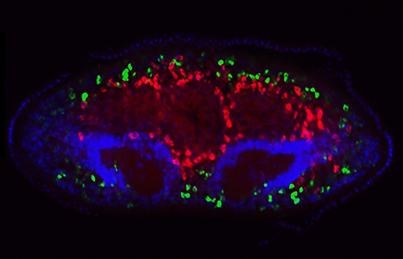

In the Arabidopsis root, xylem is organised into a central file of metaxylem that is flanked by protoxylem. Xylem fate is determined by HD-ZIP III transcription factors; high levels promote metaxylem formation whereas low levels specify protoxylem. The factors that downregulate HD-ZIP III levels are known but those that promote HD-ZIP III expression have remained elusive. Yunde Zhao, Ykä Helariutta, Jan Dettmer and colleagues now show that auxin biosynthesis promotes HD-ZIP III expression and metaxylem specification in Arabidopsis ( The transcriptional co-factor Yorkie (Yki; YAP in vertebrates) is a key effector of the Hippo signalling pathway and has been implicated in growth control and patterning, as well as stem cell regulation and regeneration, in flies and vertebrates. Now, on

The transcriptional co-factor Yorkie (Yki; YAP in vertebrates) is a key effector of the Hippo signalling pathway and has been implicated in growth control and patterning, as well as stem cell regulation and regeneration, in flies and vertebrates. Now, on  Collective cell migration occurs in many developmental contexts but a full understanding of this process has been hampered by a lack of quantitative analyses in 3D in vivo contexts. Using the zebrafish lateral line primordium as a model, Darren Gilmour and co-workers set out to tackle this problem (

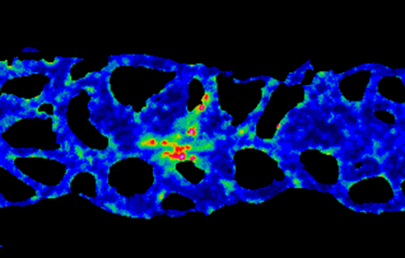

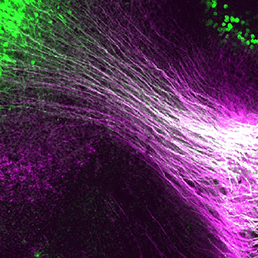

Collective cell migration occurs in many developmental contexts but a full understanding of this process has been hampered by a lack of quantitative analyses in 3D in vivo contexts. Using the zebrafish lateral line primordium as a model, Darren Gilmour and co-workers set out to tackle this problem ( During nervous system development, navigating axons ‘decide’ whether or not to cross the midline. Various factors that influence axon guidance and midline crossing have been identified but it remains unclear if any one transcription factor can drive the complete midline crossing transcriptional programme. Here (

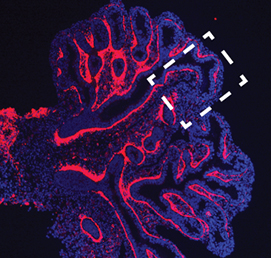

During nervous system development, navigating axons ‘decide’ whether or not to cross the midline. Various factors that influence axon guidance and midline crossing have been identified but it remains unclear if any one transcription factor can drive the complete midline crossing transcriptional programme. Here ( In mice, the formation of lymphatic vessels (lymphangiogenesis) requires the homeodomain transcription factor Prox1. Here, Stefan Schulte-Merker and colleagues examine whether the role of Prox1 is conserved in zebrafish (

In mice, the formation of lymphatic vessels (lymphangiogenesis) requires the homeodomain transcription factor Prox1. Here, Stefan Schulte-Merker and colleagues examine whether the role of Prox1 is conserved in zebrafish ( The mesenchymal compartment of the lung plays a crucial role during lung development but, unlike its epithelial counterpart, its regulation is largely uncharacterised. Now, Gianni Carraro, Saverio Bellusci and colleagues report that miR-142-3p modulates WNT signalling to balance mesenchymal cell proliferation and differentiation during mouse lung development (

The mesenchymal compartment of the lung plays a crucial role during lung development but, unlike its epithelial counterpart, its regulation is largely uncharacterised. Now, Gianni Carraro, Saverio Bellusci and colleagues report that miR-142-3p modulates WNT signalling to balance mesenchymal cell proliferation and differentiation during mouse lung development ( First published in 1985, Developmental Biology by Scott F. Gilbert has been an influential textbook for a generation of scientists. Here, Timothy Weil provides a brief review of the latest (10th) edition of the series. He comments on updates to the text, highlights details of particular interest to lecturers, and compares this book with other resources available in the internet era. See the Spotlight article on p.

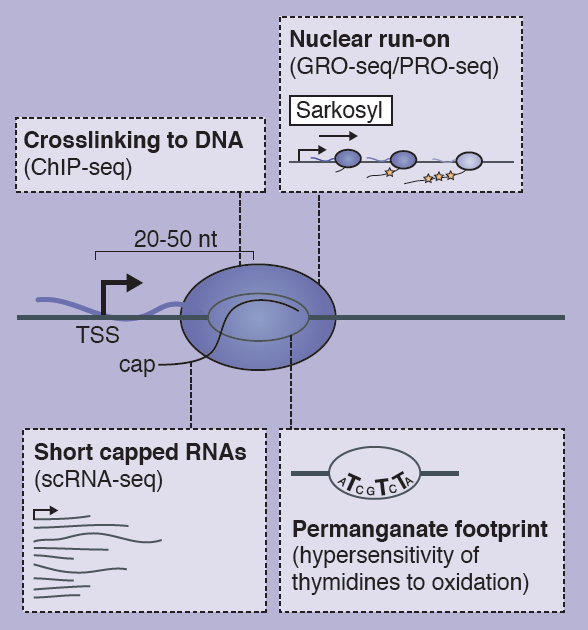

First published in 1985, Developmental Biology by Scott F. Gilbert has been an influential textbook for a generation of scientists. Here, Timothy Weil provides a brief review of the latest (10th) edition of the series. He comments on updates to the text, highlights details of particular interest to lecturers, and compares this book with other resources available in the internet era. See the Spotlight article on p.  The transcription of developmental control genes by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is commonly regulated at the transition to productive elongation, resulting in the promoter-proximal accumulation of transcriptionally engaged but paused Pol II. In their poster article, Bjoern Gaertner and Julia Zeitlinger review the mechanisms and possible functions of Pol II pausing during development. See the Development at a Glance article on p.

The transcription of developmental control genes by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is commonly regulated at the transition to productive elongation, resulting in the promoter-proximal accumulation of transcriptionally engaged but paused Pol II. In their poster article, Bjoern Gaertner and Julia Zeitlinger review the mechanisms and possible functions of Pol II pausing during development. See the Development at a Glance article on p.

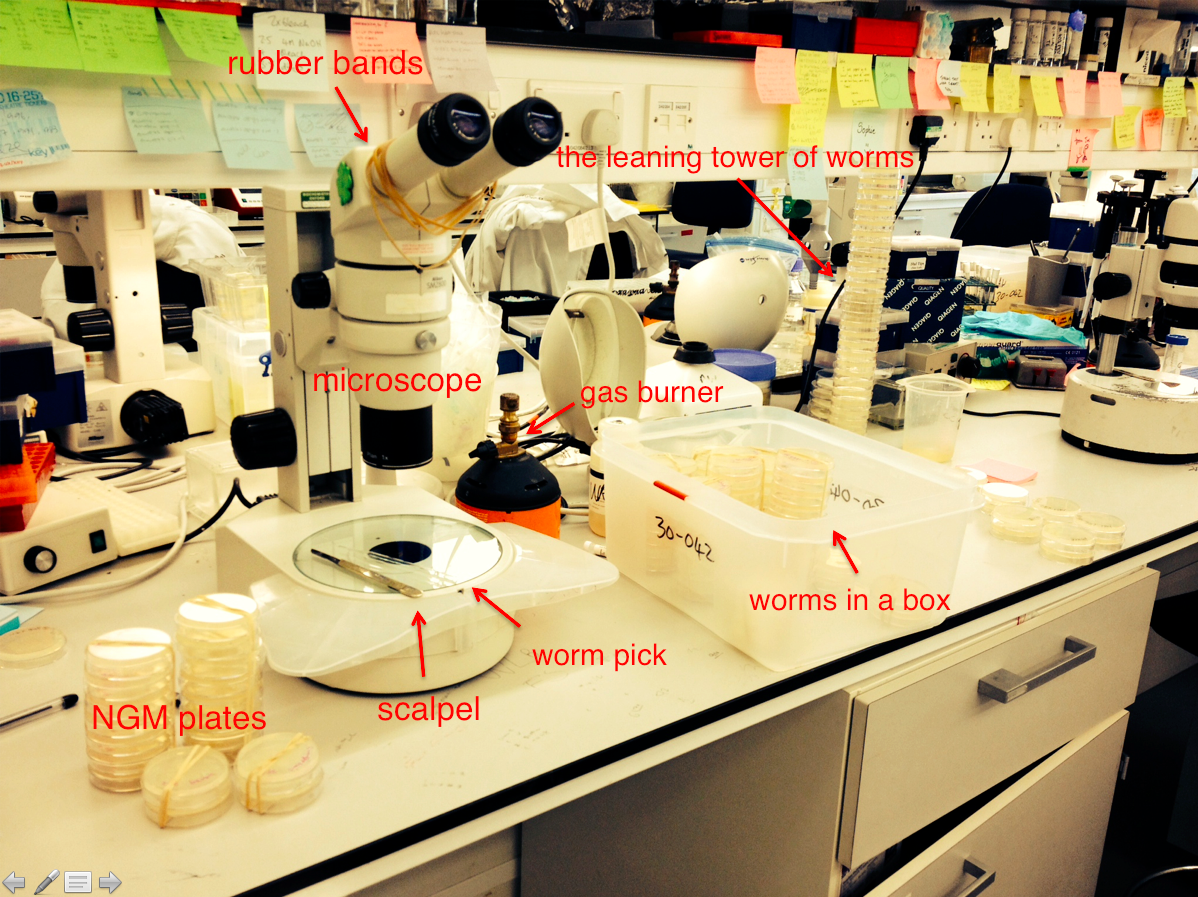

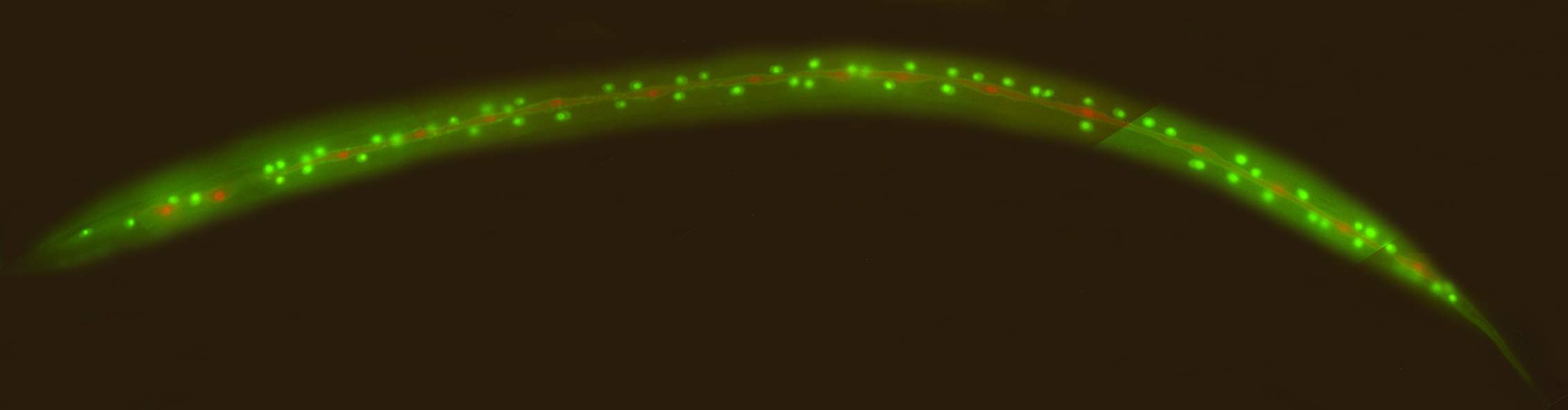

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series  (14 votes)

(14 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)