In Development this week (Vol. 139, Issue 14)

Posted by Seema Grewal, on 26 June 2012

Here are the highlights from the current issue of Development:

BRAF signalling sets astrocyte numbers

Astrocytes are the most numerous cell type in the mammalian central nervous system but little is known about the regulation of astrocyte precursor proliferation during development. Using the astrocyte marker Aldh1L1-GFP, David Rowitch and co-workers now begin to fill this gap in our knowledge (see p. 2477). The researchers identify two morphologically distinct types of proliferative astrocyte precursor in the developing mouse spinal cord: radial glia (RG) in the ventricular zone and ‘intermediate astrocyte precursors’ (IAPs) in the mantle region. Astrogenic RG and IAPs proliferate in a progressive ventral-to-dorsal manner between embryonic day 13.5 and postnatal day 3, and signalling via BRAF (a RAF isoform that is expressed in the developing nervous system) is both necessary and sufficient to promote astrocyte proliferation. Notably, temporally regulated changes in signalling and cell-cycle regulatory mechanisms restrict the mitogenic activity of BRAF during spinal cord development, thereby regulating astrocyte numbers. Together, these results provide new insights into the temporal-spatial control of astrocyte precursor proliferation during mammalian spinal cord development.

Astrocytes are the most numerous cell type in the mammalian central nervous system but little is known about the regulation of astrocyte precursor proliferation during development. Using the astrocyte marker Aldh1L1-GFP, David Rowitch and co-workers now begin to fill this gap in our knowledge (see p. 2477). The researchers identify two morphologically distinct types of proliferative astrocyte precursor in the developing mouse spinal cord: radial glia (RG) in the ventricular zone and ‘intermediate astrocyte precursors’ (IAPs) in the mantle region. Astrogenic RG and IAPs proliferate in a progressive ventral-to-dorsal manner between embryonic day 13.5 and postnatal day 3, and signalling via BRAF (a RAF isoform that is expressed in the developing nervous system) is both necessary and sufficient to promote astrocyte proliferation. Notably, temporally regulated changes in signalling and cell-cycle regulatory mechanisms restrict the mitogenic activity of BRAF during spinal cord development, thereby regulating astrocyte numbers. Together, these results provide new insights into the temporal-spatial control of astrocyte precursor proliferation during mammalian spinal cord development.

PCP gives directional Notch signalling a leg up

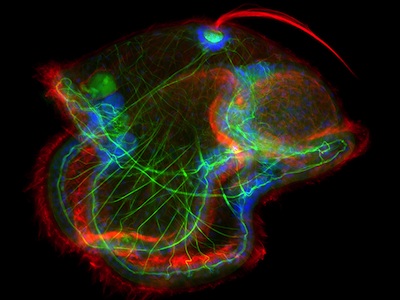

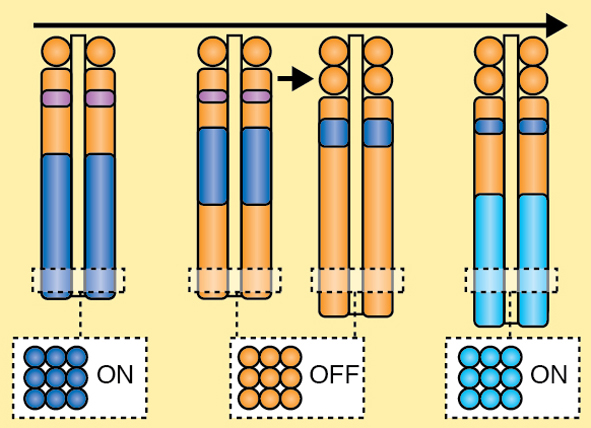

Spatial regulation of signalling pathways during development is essential. In the Drosophila leg, a stripe of cells in each segment expresses the Notch ligand Serrate (Ser) and activates the Notch pathway, which is required to specify joints, in distal cells only. Now, on p. 2584, Sarah Bray, Máximo Ibo Galindo and co-workers reveal that the planar cell polarity (PCP) proteins Frizzled and Dishevelled control this spatial restriction of Notch activation. The researchers show that these PCP proteins are enriched at the distal side of cells in the developing leg and that elimination of PCP gene function in the cells proximal to the Ser-expressing cells alleviates Notch signalling repression, resulting in ectopic joint formation. Mutants that disrupt a direct interaction between Dishevelled and Notch also reduce the efficacy of repression, whereas increased levels of Rab5, an endocytic regulator, suppress ectopic joint formation. Thus, the researchers conclude, PCP controls directional Notch signalling in the Drosophila leg by regulating the endocytic trafficking of Notch.

Spatial regulation of signalling pathways during development is essential. In the Drosophila leg, a stripe of cells in each segment expresses the Notch ligand Serrate (Ser) and activates the Notch pathway, which is required to specify joints, in distal cells only. Now, on p. 2584, Sarah Bray, Máximo Ibo Galindo and co-workers reveal that the planar cell polarity (PCP) proteins Frizzled and Dishevelled control this spatial restriction of Notch activation. The researchers show that these PCP proteins are enriched at the distal side of cells in the developing leg and that elimination of PCP gene function in the cells proximal to the Ser-expressing cells alleviates Notch signalling repression, resulting in ectopic joint formation. Mutants that disrupt a direct interaction between Dishevelled and Notch also reduce the efficacy of repression, whereas increased levels of Rab5, an endocytic regulator, suppress ectopic joint formation. Thus, the researchers conclude, PCP controls directional Notch signalling in the Drosophila leg by regulating the endocytic trafficking of Notch.

PGCs hitchhike during gastrulation

During gastrulation, the cells that give rise to internal tissues and organs move into the interior of the embryo. The gastrulation movements of endodermal and mesodermal precursors are regulated by transcription factors that also control their cell fate. However, primordial germ cells (PGCs), which also internalise during gastrulation, are transcriptionally quiescent in many species, so they must use an alternative gastrulation strategy. On p. 2547, Daisuke Chihara and Jeremy Nance identify this strategy by showing that, in C. elegans, PGCs internalise by ‘hitchhiking’ on endodermal cells. PGC adhesion to endodermal cells, they report, is mediated by HMR-1/E-cadherin, which is post-transcriptionally upregulated in PGCs through a mechanism that involves the 3′ untranslated region of hmr-1. The researchers also show that expression of HMR-1 in PGCs is necessary and sufficient to promote their internalisation, which suggests that HMR-1 does not promote PGC-endoderm adhesion through homotypic interactions. Because embryonic endoderm and PGCs are closely associated in many species, this novel post-transcriptional gastrulation strategy might be widely used to promote PGC internalisation.

During gastrulation, the cells that give rise to internal tissues and organs move into the interior of the embryo. The gastrulation movements of endodermal and mesodermal precursors are regulated by transcription factors that also control their cell fate. However, primordial germ cells (PGCs), which also internalise during gastrulation, are transcriptionally quiescent in many species, so they must use an alternative gastrulation strategy. On p. 2547, Daisuke Chihara and Jeremy Nance identify this strategy by showing that, in C. elegans, PGCs internalise by ‘hitchhiking’ on endodermal cells. PGC adhesion to endodermal cells, they report, is mediated by HMR-1/E-cadherin, which is post-transcriptionally upregulated in PGCs through a mechanism that involves the 3′ untranslated region of hmr-1. The researchers also show that expression of HMR-1 in PGCs is necessary and sufficient to promote their internalisation, which suggests that HMR-1 does not promote PGC-endoderm adhesion through homotypic interactions. Because embryonic endoderm and PGCs are closely associated in many species, this novel post-transcriptional gastrulation strategy might be widely used to promote PGC internalisation.

Foxp1/4 restrict secretory cell fates

The secretory epithelium protects the lungs from inhaled pathogens and other environmental insults that can lead to debilitating diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, by producing mucus. The epithelium contains several cell types, including secretory Clara cells and goblet cells, but the control of these cell fates during lung development and regeneration is poorly understood. Here (p. 2500), Edward Morrisey and colleagues report that the transcription factors Foxp1 and Foxp4 (Foxp1/4) control epithelial cell fate during both of these processes in mice. Loss of Foxp1/4 in the developing lung ectopically activates the goblet cell fate program, they show. Consistent with this finding, Foxp1/4 repress key factors in the goblet cell differentiation program, including anterior gradient 2 (Agr2), overexpression of which promotes the goblet cell fate in developing airway epithelium. Moreover, Foxp1/4 also restrict secretory and goblet cell differentiation during lung regeneration. Thus, by restricting cell fate choices during development and regeneration, Foxp1/4 generate the proper balance of functional epithelial lineages in the lung.

The secretory epithelium protects the lungs from inhaled pathogens and other environmental insults that can lead to debilitating diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, by producing mucus. The epithelium contains several cell types, including secretory Clara cells and goblet cells, but the control of these cell fates during lung development and regeneration is poorly understood. Here (p. 2500), Edward Morrisey and colleagues report that the transcription factors Foxp1 and Foxp4 (Foxp1/4) control epithelial cell fate during both of these processes in mice. Loss of Foxp1/4 in the developing lung ectopically activates the goblet cell fate program, they show. Consistent with this finding, Foxp1/4 repress key factors in the goblet cell differentiation program, including anterior gradient 2 (Agr2), overexpression of which promotes the goblet cell fate in developing airway epithelium. Moreover, Foxp1/4 also restrict secretory and goblet cell differentiation during lung regeneration. Thus, by restricting cell fate choices during development and regeneration, Foxp1/4 generate the proper balance of functional epithelial lineages in the lung.

Limb induction Bmps along

The molecular pathways that control limb bud patterning and outgrowth are well understood but less is known about limb field initiation. The current model for this process proposes that retinoic acid sits at the top of a signalling cascade that induces the apical ectodermal ridge, the signalling centre for limb outgrowth. Bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp) signalling, which is involved in later limb development, plays no part in this model, but Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte and colleagues recently noticed that Xenopus tadpoles exposed to the Bmp inhibitor Noggin during tail regeneration sometimes develop extra hindlimbs. Here (p. 2557), the researchers show that temporary inhibition of Bmp signalling by overexpression of noggin or by using a synthetic Bmp inhibitor is sufficient to induce extra pectoral fins in zebrafish as well as extra limbs in Xenopus. Bmp signalling, they report, acts in parallel with retinoic acid signalling, possibly by inhibiting the known limb-inducing gene wnt2ba. Based on these results, the researchers propose an expansion of the existing limb induction model.

The molecular pathways that control limb bud patterning and outgrowth are well understood but less is known about limb field initiation. The current model for this process proposes that retinoic acid sits at the top of a signalling cascade that induces the apical ectodermal ridge, the signalling centre for limb outgrowth. Bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp) signalling, which is involved in later limb development, plays no part in this model, but Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte and colleagues recently noticed that Xenopus tadpoles exposed to the Bmp inhibitor Noggin during tail regeneration sometimes develop extra hindlimbs. Here (p. 2557), the researchers show that temporary inhibition of Bmp signalling by overexpression of noggin or by using a synthetic Bmp inhibitor is sufficient to induce extra pectoral fins in zebrafish as well as extra limbs in Xenopus. Bmp signalling, they report, acts in parallel with retinoic acid signalling, possibly by inhibiting the known limb-inducing gene wnt2ba. Based on these results, the researchers propose an expansion of the existing limb induction model.

Out-Foxed: dopaminergic progenitor specification

During nervous system development, the transcription factors Foxa1 and Foxa2 regulate specification of the floor plate and of midbrain dopaminergic (mDA) neurons. However, whether Foxa1 and Foxa2 act directly or indirectly by regulating the expression of sonic hedgehog (Shh), which has similar roles, is unclear. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing, Siew-Lan Ang and colleagues now identify 9160 Foxa2 binding sites that are associated with 5409 genes in embryonic stem cell-derived mDA neuron progenitors (see p. 2625). Foxa2 directly and positively regulates key determinants of mDA neurons, the researchers report, and negatively inhibits transcription factors expressed in the ventrolateral midbrain. It also negatively regulates multiple components of the Shh signalling pathway and upregulates the expression of floor plate factors involved in controlling axon trajectories. These and other results represent the first comprehensive characterisation of Fox2a targets in mDA neuron progenitors and provide a framework for understanding the gene regulatory networks that control the development of this important progenitor population.

During nervous system development, the transcription factors Foxa1 and Foxa2 regulate specification of the floor plate and of midbrain dopaminergic (mDA) neurons. However, whether Foxa1 and Foxa2 act directly or indirectly by regulating the expression of sonic hedgehog (Shh), which has similar roles, is unclear. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing, Siew-Lan Ang and colleagues now identify 9160 Foxa2 binding sites that are associated with 5409 genes in embryonic stem cell-derived mDA neuron progenitors (see p. 2625). Foxa2 directly and positively regulates key determinants of mDA neurons, the researchers report, and negatively inhibits transcription factors expressed in the ventrolateral midbrain. It also negatively regulates multiple components of the Shh signalling pathway and upregulates the expression of floor plate factors involved in controlling axon trajectories. These and other results represent the first comprehensive characterisation of Fox2a targets in mDA neuron progenitors and provide a framework for understanding the gene regulatory networks that control the development of this important progenitor population.

PLUS…

Somitogenesis

A segmented body plan is fundamental to all vertebrate species. Segmentation is initiated very early in the developing embryo during the process of somitogenesis. Here, Dale and colleagues provide an overview of somitogenesis and highlight the key events involved in each stage of segmentation. See the Development at a Glance poster on p. 2453.

A segmented body plan is fundamental to all vertebrate species. Segmentation is initiated very early in the developing embryo during the process of somitogenesis. Here, Dale and colleagues provide an overview of somitogenesis and highlight the key events involved in each stage of segmentation. See the Development at a Glance poster on p. 2453.

Stem cell powwow in Squaw Valley

The Keystone Symposium entitled ‘The Life of a Stem Cell: from Birth to Death’ was held at Squaw Valley, CA, USA in March 2012. The meeting brought together researchers from across the world and showcased the most recent developments in stem cell research. Here, Chambers and Schroeder review the proceedings at this meeting and discuss the major advances in fundamental and applied stem cell biology that emerged. See the Meeting Review on p. 2457

The Keystone Symposium entitled ‘The Life of a Stem Cell: from Birth to Death’ was held at Squaw Valley, CA, USA in March 2012. The meeting brought together researchers from across the world and showcased the most recent developments in stem cell research. Here, Chambers and Schroeder review the proceedings at this meeting and discuss the major advances in fundamental and applied stem cell biology that emerged. See the Meeting Review on p. 2457

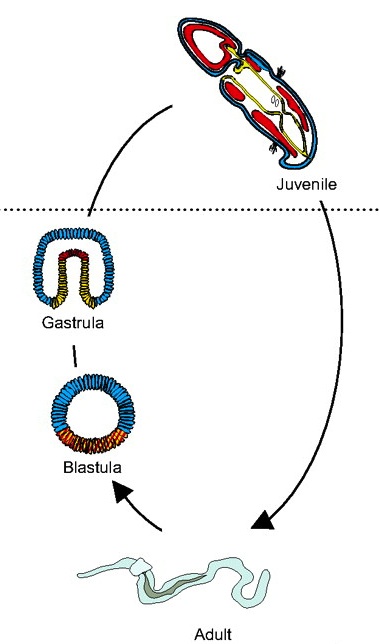

Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: hemichordates

Hemichordates are a deuterostome phylum and closely related to chordates. They have thus been used to gain insights into the origins of deuterostome and chordate body plans. Rottinger and Lowe introduce representative hemichordate species with contrasting modes of development and summarize recent findings that are beginning to yield important insights into deuterostome developmental mechanisms. See the Primer on p. 2463

Hemichordates are a deuterostome phylum and closely related to chordates. They have thus been used to gain insights into the origins of deuterostome and chordate body plans. Rottinger and Lowe introduce representative hemichordate species with contrasting modes of development and summarize recent findings that are beginning to yield important insights into deuterostome developmental mechanisms. See the Primer on p. 2463

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet) (4 votes)

(4 votes) The Young Embryologist Network (or YEN for short) held its fourth annual meeting this year on the 1st June. The conference began as a small afternoon gathering in a lecture room at UCL, but over the years it has now become a fully catered day-long event, this year filling a huge lecture theatre at the Institute for Child Health. Since the start, the ultimate aim of the meeting has been to promote interaction and collaborations between early career researchers working in developmental biology. The organisers themselves are also early career scientists, this year coming from UCL, the Institute of Child Health, NIMR and Kings College London.

The Young Embryologist Network (or YEN for short) held its fourth annual meeting this year on the 1st June. The conference began as a small afternoon gathering in a lecture room at UCL, but over the years it has now become a fully catered day-long event, this year filling a huge lecture theatre at the Institute for Child Health. Since the start, the ultimate aim of the meeting has been to promote interaction and collaborations between early career researchers working in developmental biology. The organisers themselves are also early career scientists, this year coming from UCL, the Institute of Child Health, NIMR and Kings College London.