Of TOR and Tide: Metabolism Beyond the Model #MetabolismMondays

Posted by Shefali Shefali, on 28 April 2025

All the world’s a metabolic dance, early career scientists are leading the way!

Emerging perspectives in metabolism

X: @eudald_pascual

Bluesky: @eudaldpascual.bsky.social

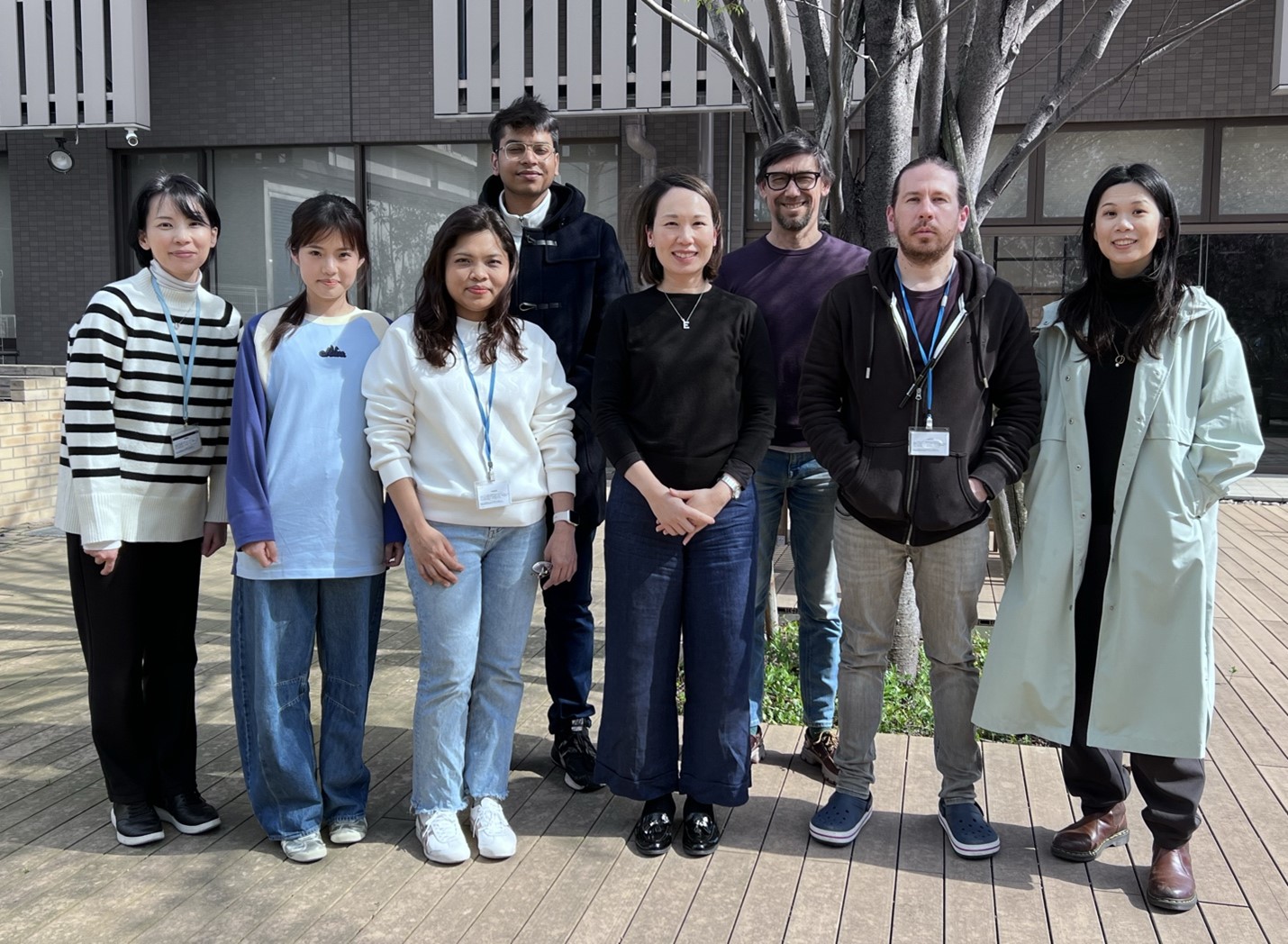

This week we will get to know insights from Dr. Eudald Pascual-Carreras, who is a postdoctoral researcher in the Multicellgenome lab at IBE Barcelona where he’s studying how metabolism regulates the cell cycle at the origin of animal multicellularity. Before joining IBE, he conducted postdoctoral work in the Steinmetz Group at the Michael Sars Centre, University of Bergen, Norway. Eudald has long been fascinated by how nutrient-dependent signaling influences stem cell proliferation and growth, approaching these questions using unique model systems like the planarian flatworms and the sea anemones. Keep reading to learn about his journey through the world of metabolism—and why curiosity driven basic science remains at the heart of it all. Along the way, he’s embraced the value of mentorship, stayed motivated through scientific challenges, and remained rooted in a deep curiosity for basic biology. Discover his journey through metabolism and learn about the mindset that keeps him going. Give him a follow over twitter or bluesky and check out his work here .

What was your first introduction to the field of metabolism? What inspired you to specialize in metabolic studies using two incredibly unique systems – the planaria flatworms and the sea anemones ?

I can clearly remember my first introduction to metabolism during high school biology class. My teacher explained how glucose is broken down, the Krebs cycle, how ATP is generated. I was fascinated by the intricated biochemical pathways that sustain life. Later, in university, I took an animal physiology course that provided a broader biochemical perspective.

For my PhD, I decided to study planarians due to their remarkable body plasticity. These animals can regenerate and modulate their body size depending on the nutrient availability. Initially, my research focused on regeneration, and metabolism wasn’t my main area of interest. However, over time, my focus shifted toward understanding the regulation of animal growth. This eventually led me to pursue a postdoctoral position in a Nematostella lab, where I kept exploring how nutritional changes influence organismal growth.

Classic research organisms such as Drosophila, C. elegans and mice have a predetermined, fixed body size. In contrast, the unique organisms I study can grow and shrink throughout their lifetime, a trait common among many non-bilaterian animals, including sponges, corals, sea anemones and ctenophores. This suggests that body plasticity is likely ancestral to all animals. Studying these organisms has allowed me to explore fundamental questions about the evolution of animal growth, the mechanisms that regulate it and the intricate interplay between metabolism and genetics.

What sparked your interest in exploring nutritional and metabolic aspects of animal development through the lens of cell cycle and cell fate? Your work intersects metabolism, development and evolution. How do you integrate these disciplines in your research, and what unique insights have emerged from this approach?

Planarians and Nematostella can rapidly adjust their body size in response to nutrient availability. In both cases, cell number drives organismal growth, making the regulation of cell proliferation a crucial factor. This sparked my interest in understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms that enable these animals to adapt. Therefore, I began studying the cell cycle, which I consider a fundamental cornerstone of this process. I found it fascinating that a such a highly conserved process as cell cycle can exhibit remarkable plasticity – pausing or adjusting its duration to accommodate different nutrient conditions.

Trained as a developmental biologist, I became increasingly interested in evolutionary questions during my PhD. Deciphering how developmental processes have evolved has always been on my interest. Integrating a metabolic perspective into this field adds a new layer of complexity that has been overlooked in evolutionary developmental biology. I believe this perspective has the potential to reshape fundamental concepts in cell biology, physiology and developmental biology.

Can you briefly summarize how you’re using Nematostella to uncover unique mechanisms by which body plasticity responds to environmental inputs, particularly how stem or progenitor cell populations driving this plasticity adapt to nutritional cues?

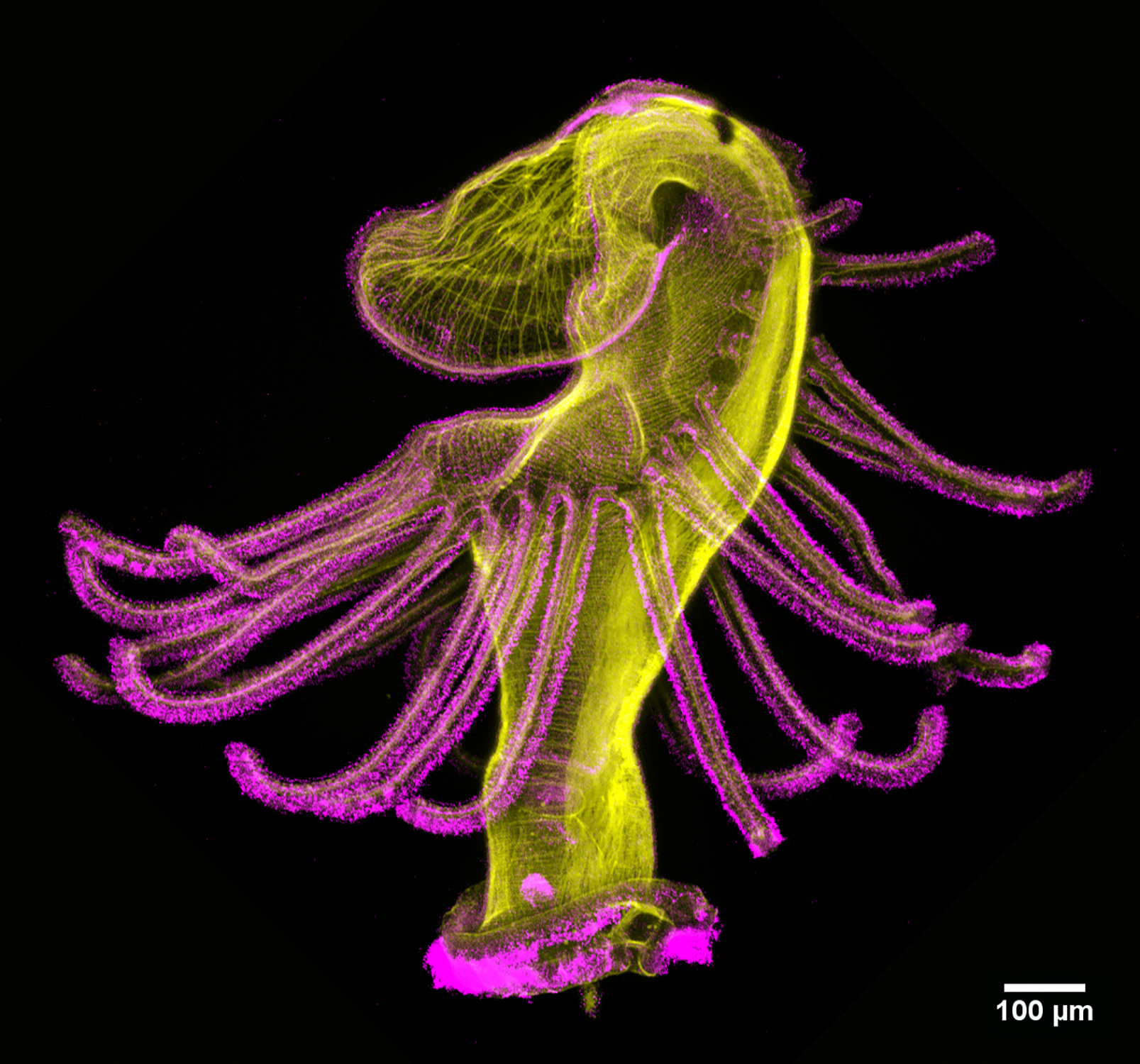

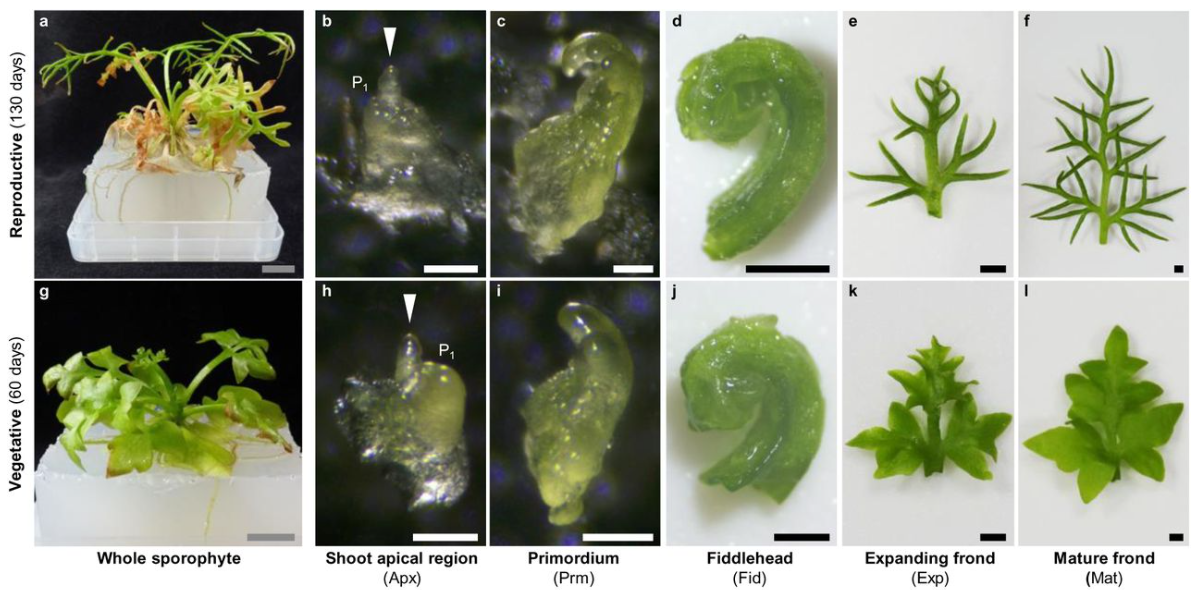

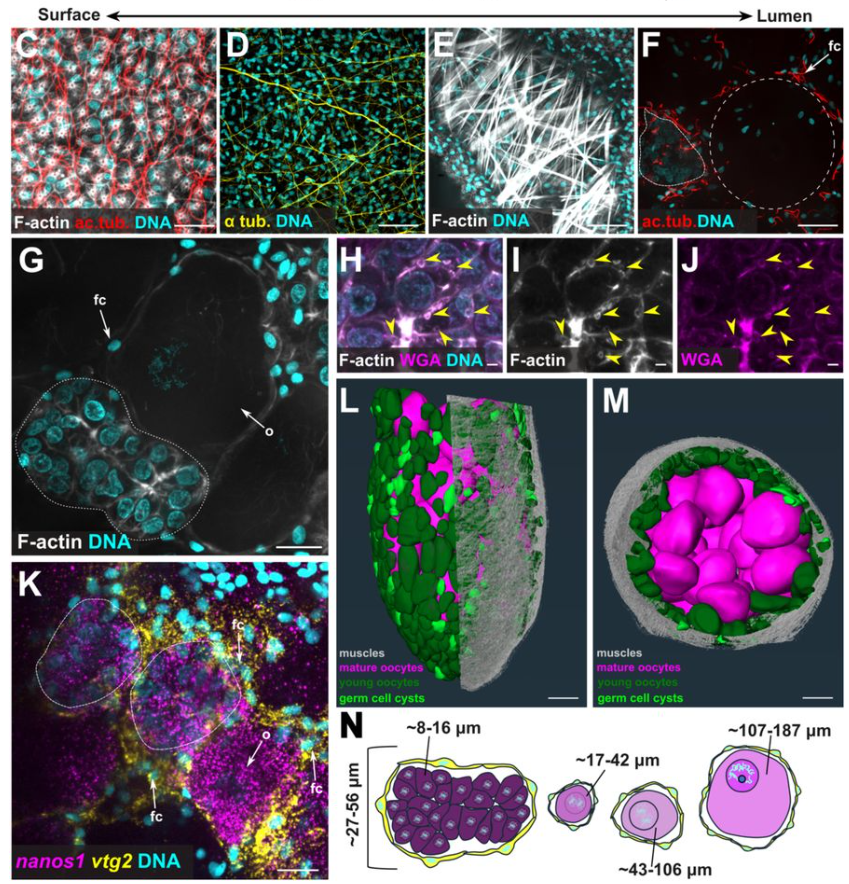

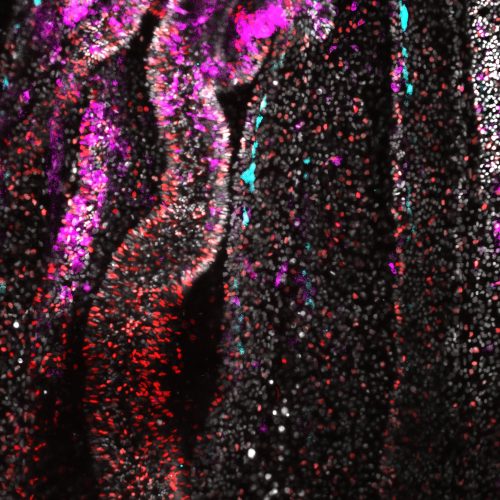

Nematostella vectensis has emerged as a powerful research organism for studying body plasticity in response to environmental changes, including

nutrient availability and temperature. Nematostella polyps exhibit a remarkable resilience during starvation conditions, capable of surviving over 200 days without food. In Steinmetz lab, we observed that after

prolonged starvation, these animals can be refed and return to their original body size within two weeks.

Our research demonstrated that changes in cell

number and cell proliferation directly correlated with organismal growth (doi: 10.1242/dev.202926). This led us to ask a fundamental question: which cells

contribute to this remarkable organismal growth? At

the same time, the lab was also investigating the identification and characterization of a multipotent stem/progenitor population that contributes to both germline and somatic tissues (doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-52806-4). My project naturally evolved from these findings – I studied how this multipotent stem/progenitor population behaves under starvation and refeeding conditions. Essentially, my goal was to move from the organismal level to the cellular and molecular level, dissecting how this specific population adapts to the extreme nutritional shifts (doi: 10.1101/2025.02.27.640509).

Tell us about your work on nutritional control of cellular quiescence and how Nematostella is a unique model to answer questions about nutrient dependent quiescence. Summarize your key findings on cell cycle dynamics, the signaling pathways involved, and how these insights differ from known mechanisms in yeast and mammals.

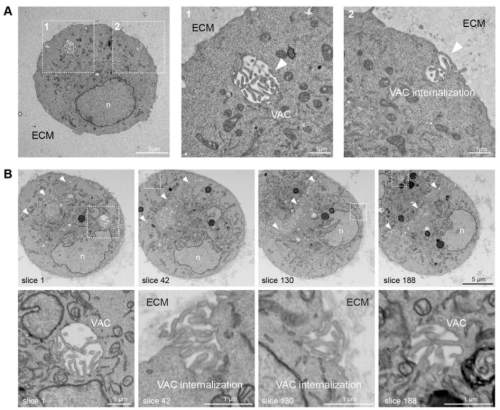

When we began studying how starvation affects this stem/progenitor population, we considered different hypotheses based on observation in planarians and Hydra. In these organisms, stem cell populations (neoblast for planarians and i-cells for Hydra) continue dividing even under starvation. However, in Nematostella, we observed that the stem/progenitor population exhibited a low division rate, suggesting that these cells might enter a state of cellular quiescence.

We then found differences in cell cycle phase distribution depending on the duration of the starvation. The longer the starvation period, the deeper the quiescent state these cells entered! This progressive deepening of quiescence following nutrient withdrawal had only been observed in yeast and cell culture models, never in an organismal level! What is fascinating is that after refeeding, these cells are primed to re-enter the cell cycle in short-term condition while the re-entry was delayed following prolonged starvation.

Our findings position Nematostella as a unique in vivo model to study nutrient-dependent quiescence, and all it requires is subjecting animals to different starvation durations. Surprisingly simple yet incredibly powerful!

Specifically, we have found that starvation induces a G1/G0 quiescence state. During short-term starvation, some cells remain cycling, and after refeeding, quiescent cells rapidly re-enter the cell cycle. However, after long term starvation, the majority of the cells have entered a deep quiescent state, and their cell cycle re-entry is delayed upon refeeding! While we are still investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying quiescence acquisition, we have identified that TOR signalling is essential for feeding-dependent cell cycle re-entry!

Tell us about the experimental challenges you encountered during this project?

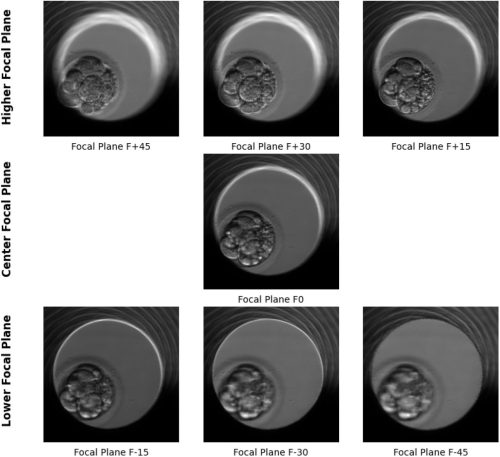

This project was a major challenge from the start. I spent my first year establishing quantitative flow cytometry analysis in Nematostella. Since the stem/progenitor population is located deep with the tissue and cannot not be imaged directly, I quickly realized that understanding cell cycle dynamics would require a tightly controlled time course experiments. This meant meticulous planning, and of course, having the support of colleagues and undergrads was essential.

To optimize time course experiments, I decided to try something slightly different. From T0 to 12 hours post feeding (hpf), I could sample continuously, which meant spending at least 14 hours in the lab. However, for the later time points (15, 18 and 21 hpf), instead of staying up all night, I strategically delayed the last feeding 3, 6 or 9 hours, allowing me to collect the samples the following morning. Naturally, I ensured that this adjustment had no circadian effects.

This approach not only made the experiment more manageable but also allowed me to generate high-resolution temporal data without requiring overnight shifts. Though long hours were certainly still part of the process!

Before this, you worked on planaria and identified a novel gene family – blitzschnell, which coordinates cell proliferation and differentiation in response to nutritional availability. Please tell us about your exciting findings.

This was a truly unique project. Characterizing the function of a novel gene family came with significant challenges, as we had no reference to guide our understanding of the phenotype. It took time to piece everything together, but our findings were exciting!

One of our key discoveries was that the transcription of this gene family, blitzschnell, is directly regulated by nutrient intake! Moreover, its function is critical for controlling the cell number by balancing cell proliferation and cell death. In planarians, this regulation may be linked to the requirement for continuous and rapid modulation of cell numbers in response to nutrient availability (doi: 10.1242/dev.184044)

How do you think the fields of studying evolution and metabolism overlap? How do the two model systems you worked with differ in terms of nutrient-dependent regulation ?

Evolution and metabolism are deeply intertwined! Nutritional regulation is likely one of the most ancient evolutionary mechanisms. In unicellular eukaryotes, one of the earliest forms of cellular regulation is nutrient-dependent division: cells divide when food is available, and halt division when it is scarce. In multicellular organisms, this regulation has become more complex due to cell type and tissue specialization, certain tissues sense the nutrients and signal other cells to divide.

While nutrient-dependent growth regulation has been well studied in some animal tissues and cell cultures, we still lack a broader understanding from an organismal perspective. Using planarians and Nematostella as models, we can explore how stem cell populations that drive organismal growth respond to nutritional cues. One of the key differences we have observed is that in Nematostella, stem cells enter a quiescent state during starvation, whereas in planarians, this is less clear. Neoblasts continue proliferating even in the absence of food. The cell cycle dynamics of neoblasts during starvation remain poorly understood, with some results suggesting that starvation prolongs the G2 phase, allowing some neoblast to re-enter the cycle upon refeeding. However, this has not been definitively proven.

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of how nutrient-dependent regulation evolved, more organisms with body plasticity, such as ctenophores, Ciona, and sponges, should be studied. These models could provide crucial insights into the cellular mechanisms underlying metabolic control of animal growth.

How have different animals evolved to respond to nutritional and metabolic stresses? TOR signaling is conserved from yeast to humans, but are there organism specific differences in which the pathway is utilised ?

Yes, the signalling pathways are highly conserved across species. TOR signalling is required for organismal growth and cell proliferation in both Nematostella and planarians. What is particularly interesting is how these different animals utilize the same conserved pathway in distinct ways. While both rely on TOR signalling, they employ different strategies to cope with nutrient availability. As I mentioned earlier, Nematostella stem cells enter a quiescent state during starvation, while planarian neoblasts continue proliferating, even under nutrient-deprived conditions. Despite these differences, both organisms use the same fundamental molecular toolkit, illustrating the remarkable versatility of conserved signalling mechanisms across evolution.

What role does curiosity play in your life, both within and outside of science? How important it is for you to answer basic science questions on metabolic signaling and how do you see its impact on human health/relevance ?

Curiosity is at the core of my scientific journey. I am deeply interested in basic science, particularly in understanding how developmental processes are regulated, how cells integrate surrounding signals, and how the metabolome interacts with the transcriptome and signalling pathways. These fundamental questions drive my research, as uncovering mechanisms not only expands our knowledge of biology but also lays the groundwork for better understanding of human biology and health.

Although my research is not explicitly focused on human biology, I believe that the questions I explore have significant implications for human health. Fundamental discoveries in model organisms often provide insights into conserved biological processes, ultimately influencing biomedical research and our understanding of disease mechanisms.

What are your upcoming plans? What metabolic pathways or signals you aim to investigate further to understand their role in stem cell regulation?

The Steinmetz group at the Michael Sars Center (UiB, Bergen, Norway), where I conducted my postdoc, remains deeply interested in studying the metabolic regulation of this stem/progenitor cell population. Our ongoing work aims to uncover the transcriptomic and epigenetic changes these cells can undergo in response to nutritional shifts. Additionally, the group is exploring metabolic changes at the organismal level.

Personally, I am about to start a new postdoctoral position, where I will investigate the metabolic regulation of the cell cycle in the context of the transition of animal multicellularity. As mentioned, nutritional regulation is likely one of the most ancient evolutionary mechanisms. I plan to leverage a facultative multicellular organism, whose life cycle includes distinct unicellular and multicellular stages. I am particularly curious to understand how metabolism influences multicellularity transition, whether nutritional gradients are generate within cell aggregates and whether shifts in metabolic state serve as prerequisites for multicellularity.

What changes have you seen in the scientific community in regard to studying these unique aspects of metabolic signaling in unconventional systems? How do you think scientific paradigms around gaining new insights from non-model organisms will evolve in the coming decades? Are we moving toward a more nuanced understanding, or do you see potential pitfalls?

The scientific community is increasingly recognizing that non-classic research organisms can provide valuable insights into the more fundamental questions. As a developmental biologist, I am well aware of the critical role that non-classic research organisms have played in advancing our understanding of core processes. For example, the discovery of cyclins in sea urchins. Similarly, I believe that studying unconventional model can unveil new and extraordinary metabolic processes that may have previously been thought to exist only in unicellular eukaryotes.

Moreover, one aspect that has often been overlooked in recent years is the metabolic state of organisms when designing experiments. As we gather more data, it will become increasingly important for each scientific community to establish standardized protocols to improve reproducibility and ensure more meaningful interpretations of results. By integrating a more nuanced understanding of metabolic context, we can refine experimental approaches and uncover deeper insights into the fundamental principles of biology.

How do you see the future of metabolism evolve with the new upcoming techniques – what are you most excited about ?

I would love to establish metabolic sensing lines, as my work over the past few years primarily relied on fixed tissue, making it challenging to assess the dynamic nature of metabolic processes. Having live metabolic sensor lines would be a game-changer, allowing us to directly observe and analyze the metabolic state of a cell under the microscope in real time! Additionally, I believe it is crucial to move beyond relying solely on metabolomics. While metabolomic profiling provides valuable insights, integrating real-time metabolic imaging with other approaches will offer a more comprehensive understanding of cellular metabolism and its regulation. These advancements will open new avenues for studying metabolism in a more dynamic and physiologically relevant context.

Were there any pivotal moments that shaped your career path? What’s an unexpected place you’ve found inspiration for your work?

I don’t think I’ve had a single pivotal moment that shaped my career. Instead, I see my scientific journey as continuous progression. However, one thing I am certain of is that having good professors and mentors was essential in building my scientific confidence, which, in itself, is crucial for a successful career. Equally important is making time to disconnect and relax. Some of my ideas have come not while working in the lab, but while running, hiking, spending time with my family, or even having a beer with friends, often in moments when I wasn’t thinking about science at all. Stepping away from research can provide the mental space needed for creative problem-solving.

What advice would you offer to students and early career scientists interested in exploring the intersections of nutrition/metabolism and cell fate decisions ?

For early-career scientists interested in exploring the intersections of nutrition, metabolism, and cell fate, my advice would be to choose an organism with a significant body or developmental plasticity. These are the most fascinating systems, and there is still so much to learn from them!

How do you maintain a balance between your rigorous research activities and personal life? Are there hobbies or practices you find particularly rejuvenating?

Finding balance isn’t easy, and I’ve learned mostly through trial and error. I try to be as focused and productive as possible while I’m in the lab, but once I leave, I make a conscious effort to disconnect. That doesn’t mean I never check an email or skim through a paper in the evenings, but I don’t make it a habit. Setting boundaries has helped me maintain a healthier work-life balance.

I also make time to run at least once a week. It’s a great way to clear my mind, organize my thoughts, and stay active. At the end of the day, having a fulfilling life outside of academia is essential for me. It keeps me motivated and ultimately makes me a better scientist.

If you hadn’t embarked on a career in biological research, what other profession might you have pursued, and why?

I would be a high school science teacher. Over the past few years, I’ve had the opportunity to teach both high school and undergraduate students, and I’ve genuinely enjoyed the experience. Teaching allows me to share my passion for science while inspiring the next generation of students.

I also had an incredible high school biology teacher who played a significant role in shaping my path. His enthusiasm and teaching style sparked my interest in biology, and I wouldn’t be where I am today without that influence.

Check out the article All the world’s a metabolic dance, and how early career scientists are leading the way !!

(3 votes)

(3 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)