An interview with Deepak Srivastava

Posted by the Node, on 16 June 2015

This interview was first published in Development.

Deepak Srivastava is a Director at the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease and a Distinguished Professor in Paediatric Developmental Cardiology at the University of California, San Francisco. As well as caring for sick children as a physician at the Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco, he runs an active research group that studies the biology of heart development and regeneration. In March 2015, we met up with Deepak and asked him about his career.

How did you first become interested in science, and was there anyone in particular who inspired you?

How did you first become interested in science, and was there anyone in particular who inspired you?

Well, I actually grew up around education and science – my father is a biochemist and my mother was a schoolteacher – so I was naturally drawn to both of these areas and those are the areas that I largely focus on today. What I enjoy most is discovery and training the next generation.

How did this then lead to a career in medicine?

In addition to science, I was always interested in medicine: when I was growing up, if a kid got hurt in the playground I was the first to run up and make sure that they were okay. I’ve always been drawn to helping other people and so marrying medicine and science, as I’ve done, was just natural for me.

You started off in paediatrics but how did your interest in cardiovascular biology develop?

I did my residency in paediatrics and, during this time, I was repeatedly drawn to understanding the life-death situation seen in children with heart disease. At the time, there were very few scientists involved in basic discovery within the paediatric cardiology field, and I was advised by many that it would not be a good career choice if I wanted to do science. But I followed my passion, which was taking care of those types of patients, who mostly had defects in cardiac formation during embryonic development. Fortunately, the field of molecular developmental biology was just emerging at that time, so there turned out to be a tremendous opportunity to really develop and help the cardiovascular development field grow from its infancy. I’ve had the opportunity to participate in this field for over 20 years now, and seeing it mature – to the point where we now understand quite a bit about how the heart forms and what things go wrong in the setting of heart disease in children – has been really rewarding.

In addition to being an active clinician you run a successful research programme. Has doing research always been important to you?

Doing research has always been important. From the moment I decided to go to medical school it was with the understanding that I would combine my medical studies with a research programme. Although this took time, I’ve been fortunate to be able to leverage both aspects, in terms of understanding the basic biological processes that go awry in disease as well getting the motivation for doing basic science from my clinical experiences. It has been challenging to do both, but I think that the key to many of our discoveries has come from having that clinical perspective.

Much of your research is now geared towards translational goals, with the aim of regenerating heart tissue. But how has basic developmental biology guided this?

The bulk of our laboratory is still doing basic science but we certainly want to drive our discoveries towards translation because, at the end of the day, that’s why we’re doing the work. But it’s certainly true that all of our regenerative medicine work is inspired by our understanding of the developmental biology of the heart. In

our attempts to regenerate heart muscle through cardiac reprogramming, we’re essentially deploying nature’s own molecular tools, which we’ve learned about from studying the embryo, and reintroducing them into the adult heart to create new muscle.

In terms of that big goal – regenerating the heart – do you think we’re close to being able to treat cardiovascular diseases?

I don’t think we’re close yet to being able to treat humans with the disease, but I think we’re certainly making great strides towards that goal, on many fronts. With our knowledge being driven by basic developmental biology, I’m very hopeful that over the next 5 to 10 years we will have viable approaches to either spur existing heart muscle cells to divide again in the adult, like they do in embryos, or to coax non-muscle cells into new muscle cells by reintroducing developmental signals that function in the embryo. We still have a lot of work to do but we’re in a much better position today than we’ve ever been, in terms of being able to at least see the finish line.

You’re also a Director at the Gladstone Institutes.What do you think is the key to running a successful research institute?

I think the key to running a successful institute is to be able to bring in talent from multiple disciplines and combine this in a single location, so that people are exposed to a variety of thought processes. For example, on our floor at the Gladstone Institutes we have cardiac biologists, stem cell biologists, chemists, mathematicians and engineers – all in one big open space. This means that trainees in the laboratory are constantly being bombarded with different ways to think about their problem, and

this has created a very innovative environment in which new approaches and discoveries are happening all the time. This also means that we’re doing the kind of science that no one laboratory could do by itself. Yes, you can do that through collaborations – across an institution, across the country or across the world – but I think the key is getting the trainees in close proximity to one another on a day-to-day basis, so that they’re the ones who come up with the collaborations, ideas and innovations.

What’s your advice to young researchers today?

My advice to young investigators is to find out what they’re passionate about and follow that relentlessly, even if it’s not the easiest path to follow. People shouldn’t be intimidated by the current research environment and whether it’s difficult to find funding or get jobs; if they work hard, are passionate and commit themselves to a path, good science gets funded and, ultimately, gets rewarded. If you’re passionate about what you’ve chosen to do you’ll give it everything you’ve got. But if you try to make a choice that makes sense in your mind, but not in your heart, then you’ll always be half hearted about it.

Finally, what would people be surprised to find out about you?

That, when I was young, I really wanted to be a professional tennis player. But I soon realised that I wasn’t good enough! I still play frequently and I guess that tennis is my biggest passion outside of science.

(3 votes)

(3 votes) The myelination of axons by oligodendrocytes in the nervous system is crucial for neuron function and survival. Its disruption leads to permanent functional defects, as seen in numerous severe neurological pathologies. In order to study the developmental principles of this process and develop effective regenerative strategies, Fred Gage and colleagues have developed a system that allows robust and consistent myelination in vitro (see p.

The myelination of axons by oligodendrocytes in the nervous system is crucial for neuron function and survival. Its disruption leads to permanent functional defects, as seen in numerous severe neurological pathologies. In order to study the developmental principles of this process and develop effective regenerative strategies, Fred Gage and colleagues have developed a system that allows robust and consistent myelination in vitro (see p.  After an acute wound, tight regulation of repair signalling pathways is essential to ensure wound resolution and avoid chronic tissue damage. Interestingly, the molecular signals induced during wound healing are also present in chronic wounds but their specific roles in each situation remain mysterious. In order to identify factors that contribute to chronic tissue damage, Anna Huttenlocher and co-workers (p.

After an acute wound, tight regulation of repair signalling pathways is essential to ensure wound resolution and avoid chronic tissue damage. Interestingly, the molecular signals induced during wound healing are also present in chronic wounds but their specific roles in each situation remain mysterious. In order to identify factors that contribute to chronic tissue damage, Anna Huttenlocher and co-workers (p. In most insects, the initial phase of embryogenesis involves multiple nuclear divisions to generate a syncytium, migration of the resulting nuclei to the cell cortex, followed by cellularisation. This last process has been thoroughly studied in Drosophila: the plasma membrane invaginates around the nuclei and extends to generate a basal membrane, forming a layer of epithelial cells. To what extent is this process conserved in other insects? To investigate this (see p.

In most insects, the initial phase of embryogenesis involves multiple nuclear divisions to generate a syncytium, migration of the resulting nuclei to the cell cortex, followed by cellularisation. This last process has been thoroughly studied in Drosophila: the plasma membrane invaginates around the nuclei and extends to generate a basal membrane, forming a layer of epithelial cells. To what extent is this process conserved in other insects? To investigate this (see p. Deepak Srivastava is a Director at the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease and a Distinguished Professor in Paediatric Developmental Cardiology at the University of California, San Francisco. As well as caring for sick children as a physician at the Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco, he runs an active research group that studies the biology of heart development and regeneration. In March 2015, we met up with Deepak and asked him about his career. See the Spotlight article on p.

Deepak Srivastava is a Director at the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease and a Distinguished Professor in Paediatric Developmental Cardiology at the University of California, San Francisco. As well as caring for sick children as a physician at the Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco, he runs an active research group that studies the biology of heart development and regeneration. In March 2015, we met up with Deepak and asked him about his career. See the Spotlight article on p.  Rudolf Jaenisch is a Professor of Biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a founding member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and the current president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR). In recognition of his pioneering research, he recently received the 2015 March of Dimes Prize in Developmental Biology. At the recent Keystone Meeting on ‘Transcriptional and Epigenetic Influences on Stem Cell States’ in Colorado, we had the opportunity to talk to him about his life and work. See the Spotlight article on p.

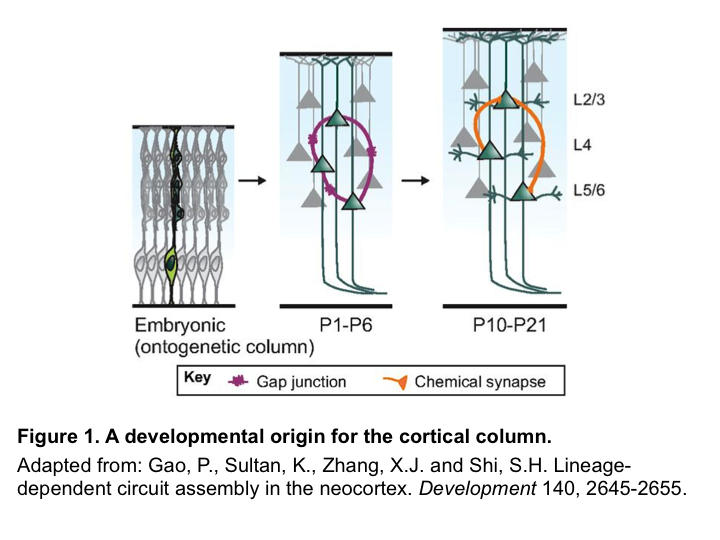

Rudolf Jaenisch is a Professor of Biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a founding member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and the current president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR). In recognition of his pioneering research, he recently received the 2015 March of Dimes Prize in Developmental Biology. At the recent Keystone Meeting on ‘Transcriptional and Epigenetic Influences on Stem Cell States’ in Colorado, we had the opportunity to talk to him about his life and work. See the Spotlight article on p.  Neurons are highly polarized cells with structurally and functionally distinct processes called axons and dendrites. This polarization, which underlies the directional flow of information in the central nervous system, is crucial for correct development and function. This short review and accompanying poster highlight recent advances in this fascinating field, with an emphasis on the signaling mechanisms underlying axon and dendrite specification in vitro and in vivo. See the Development at a Glance article on p.

Neurons are highly polarized cells with structurally and functionally distinct processes called axons and dendrites. This polarization, which underlies the directional flow of information in the central nervous system, is crucial for correct development and function. This short review and accompanying poster highlight recent advances in this fascinating field, with an emphasis on the signaling mechanisms underlying axon and dendrite specification in vitro and in vivo. See the Development at a Glance article on p.  The liver is a central regulator of metabolism, and liver failure thus constitutes a major health burden. Understanding how this complex organ develops during embryogenesis will yield insights into how liver regeneration can be promoted and how functional liver replacement tissue can be engineered. Here, Gordillo, Evans and Gouon-Evans review the lineage relationships, signaling pathways and transcriptional programs that orchestrate hepatogenesis. See the Review on p.

The liver is a central regulator of metabolism, and liver failure thus constitutes a major health burden. Understanding how this complex organ develops during embryogenesis will yield insights into how liver regeneration can be promoted and how functional liver replacement tissue can be engineered. Here, Gordillo, Evans and Gouon-Evans review the lineage relationships, signaling pathways and transcriptional programs that orchestrate hepatogenesis. See the Review on p.  The neural stem cells (NSCs) located in the largest germinal region of the forebrain, the ventricular-subventricular zone (V-SVZ), replenish olfactory neurons throughout life. However, V-SVZ NSCs are heterogeneous: they have different embryonic origins and give rise to distinct neuronal subtypes depending on their location. In this Review, we discuss how this spatial heterogeneity arises, how it affects NSC biology, and why its consideration in future studies is crucial for understanding general principles guiding NSC self-renewal, differentiation and specification. See the Review on p.

The neural stem cells (NSCs) located in the largest germinal region of the forebrain, the ventricular-subventricular zone (V-SVZ), replenish olfactory neurons throughout life. However, V-SVZ NSCs are heterogeneous: they have different embryonic origins and give rise to distinct neuronal subtypes depending on their location. In this Review, we discuss how this spatial heterogeneity arises, how it affects NSC biology, and why its consideration in future studies is crucial for understanding general principles guiding NSC self-renewal, differentiation and specification. See the Review on p.  (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)